Abstract

The article discusses a study conducted in the Chipinge-East District of the Manicaland Province in Zimbabwe. The possibilities of establishing local peace committees in a Zimbabwean context were analysed. The study was as a reaction to the recurring violence affecting Zimbabwean communities along the border with Mozambique. In addition, the absence of comprehensive violence-reduction measures from the Zimbabwean government and communities to address this violence was noted. An action research approach was used to conduct the study. The findings of the study revealed that the Chipinge-East community had the capacity and interest to set up a Local Peace Committee (LPC). The LPC managed to set up an early warning system to mitigate the violence which occurs in the community. The LPC members also managed to travel to other locations in Chipinge District to inform the wider community about the early warning system. Despite its notable achievements, the LPC faced obstacles which included a lack of financial resources, initial resistance, and suspicions from community members and state authorities. Despite the challenges, the LPC continues to forge ahead and serves as a model for peacebuilding in Zimbabwe.

1. Introduction

The study’s primary objective was to ascertain whether LPCs can be a viable avenue for the formulation of community-based violence-reduction strategies in communities affected by RENAMO incursions along the Zimbabwe–Mozambique border. The study was based on the Infrastructure for Peace (I4P) ideological framework espoused by peace studies’ luminaries, such as Jean Paul Lederach and Paul Van Tongeren. The study’s research was conducted using an action research methodology which is described in greater detail in the article. Suffice to say, the study was conducted through focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and structured observation. Residents and local and traditional authorities of the affected community were the central focus of the research. The research was jointly conducted with these groups and it was left to them to formulate and implement the violence-reduction strategies. This is in line with the dictates of action research. Desktop research was also conducted, wherein secondary sources were consulted. The article expands on the framework and methodology and shares the findings and recommendations of the study.

2. Background of the research

Chipinge-East constituency is located in the Chipinge District of Manicaland Province in the Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe. The community is well known for its rolling hills and valleys, its diverse array of agricultural produce and the unique dialect of its inhabitants. It is home to the Ndau culture, the Tanganda tea estates and lucrative macadamia nuts. Despite its riches, the Chipinge community has been marred by trans-boundary violence perpetrated by RENAMO (Mozambican National Resistance) rebels from Mozambique. Whenever hostilities erupt between the rebels and the FRELIMO (Liberation Front of Mozambique) government, the rebels tend to cross the border and terrorise innocent communities along the border, which include Chipinge. The Zimbabwean state has done little to quell the violence; rather, it has adopted a reactive, militaristic approach which tends to worsen the violence. The violence is not openly spoken of by community members, but the mental, emotional and physical scars are there. The fear continues to haunt their daily lives. Given this scenario, a study was conducted to test the concept of the LPC in an attempt to capacitate the community with ways to mitigate the violence perpetrated by the rebels. The study covers four decades from 1980 to 2020. The choice of the Chipinge-East Constituency was based on its proximity to the Mozambican border. It is the constituency most affected by the RENAMO violence, whenever it erupts.

3. Local Peace Committees (LPCs)

Tongeren (2013:39) defines LPCs as committees or structures formed at the level of a town or village, and their aim is to encourage and facilitate joint, inclusive peacemaking and peacebuilding processes within their own context. He calls them the cornerstone for Infrastructure for Peace (I4P), which reduces violence, solves community problems and empowers local communities to become peacebuilders. Irene (2014:151) concurs with Tongeren and adds that LPCs are part of a conflict transformation process and use basic local peacebuilding methods. Ayodele and Felix (2017:28) affirm that LPCs are tools for conflict transformation using local peacebuilding methods. They address destructive rumours, fears, mistrust, and facilitate reconciliation and social cohesion.

These definitions portray the LPCs as organisations which are formed at a grassroots level. This is what differentiates conflict transformation from other peacebuilding mechanisms. LPC peacebuilding has moved from the international and national spheres to those of local communities (Muchemwa 2015:14). The reasons for the paradigm shift from the international and national to the local sphere are twofold. The first is that the nature of conflicts in the post-Cold War era have become intranational, for instance the African civil wars. This development has reduced the effectiveness of international peacebuilding efforts, which are clearly more suited to international conflicts Secondly, it has been proven that these new conflicts are better resolved by local communities, which have a better contextual understanding of the conflicts.

Tongeren (2012:106) advises that the membership of LPCs is very important; they must be comprised of highly respected persons. These people need to be knowledgeable, competent and experienced in matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The members need to reduce violence, promote dialogue, solve problems and promote community building and reconciliation. Adam and Pkalya (2006:47) concur and state that the qualities required for members of LPCs are honesty, integrity, impartiality and neutrality, fluency in the local language, and local residency. They would also need to not be political office holders. Dube and Makwerere (2012:301), however caution that in addition to context-based resources, successful LPCs require the input of national actors and other external support. Their support is from a distance – in the form of facilitation, orientation, and national peacebuilding resources. This support is important in that it helps the local actors with a wider knowledge of how to use their experience with their respective conflicts and to arrive at a successful transformation.

Nevertheless, Tongeren (2012:108) posits that violence has been reduced in 57 per cent of the communities that have established LPCs. Chivasa (2015:88) affirms that LPCs are an effective mechanism of building peace in conflict-ravaged communities.

There are two types of Local Peace Committees (LPCs): informal and formal (Tongeren 2013:39–41). Informal LPCs are also known as Local Peace Zones/Zones of Peace. They are rooted in traditional structures such as the Council of Elders. They can be part of a nation’s I4P, be formal and driven by a government mandate, or be independent and driven by the local community. In many cases they are immune to political and government actors. Their members are volunteers who are awarded a high level of trust and commitment from members of the community. They, however, lack influence and often fail to make an impact outside of the community. Ayodele and Felix (2017:28) maintain that informal LPCs are normally established by civil society and are rarely recognised by the government. Nevertheless, the LPCs often initiate dialogue in a divided community, solve conflicts and protect their communities from violence. They can compensate for the weakness of local governance. They can be hybrid in that they can include both traditional and modern conflictresolution processes.Formal LPCs are referred to as nationally mandated LPCs by Dube and Makwerere (2012:301). They have more influence than informal LPCs. They are an important link between local and national peacebuilding. However, they are prone to manipulation by government structures. Irene (2014:157) states that these LPCs obtain their mandate from a central national structure. They are created as result of a government decision. They are nationally recognised and most of their members are from political parties, security force government bodies, and civil society. Ayodele and Felix (2017:28) cite the examples of South Africa and Sierra Leone as countries that implemented formal LPCs that were created through peace accords.

4. Global case studies of LPCs.

Some of the notable LPCs include the Wajiir Peace Committee in Kenya (WPDC), the Harambe Women’s Forum in South Africa, the Peace Community of San Jose de Apartado in Columbia, and the Zones of Peace in the Philippines. All of them have achieved a degree of success in mitigating the conflict and violence in their respective communities. Ayodele and Felix (2017:31) maintain that the WPDC is one of the most successful examples of I4P and LPCs. It is a model of conflict intervention and transformation at the community level. Issifu (2016:149) adds that the Harambe Women’s Forum managed to empower many women, and organised literacy classes for youths imprisoned under the apartheid regime. It also equipped rural people with peacebuilding and trauma healing skills. Chivasa (2015:85) states that the San Jose peace committees celebrated their 18th anniversary of peace in their territory. Irene (2014:166) states that the Philippine Zones of Peace succeeded in promoting peace, social justice and human rights in their communities.

5. Research methodology

The action research approach was employed for this study. This is because the study intended to effect a change in the issue identified by the community. The aim of the research was not to simply conduct a study and produce a set of recommendations. Rather, it wanted to go further and implement these recommendations to resolve the problem(s) identified by the community and even evaluate if the prescribed solutions are working to resolve the current predicament in the community.

Based on the literature, there are two categories of action research strategy: the academic and the political. The academic side involves the researcher conducting his/her research with the aid of research participants. As opposed to other research strategies that separate the researcher from the research participants, action research makes them equal partners; they are both important stakeholders in the research process. The research participants have a stake in the research which is equal to that of the researcher. Action research is a research strategy that equalises the power balance between the researcher and the participants. In some cases, it tips the balance of power in favour of the research participants; the role of the researcher is reduced to that of a facilitator – as noted by Muchemwa (2015:121). Greenwood and Levin (2007:03) add that action research brings together the research experts and the local stakeholders to work out a practical solution to a problem. They add that action research does research with, instead of research for, the participants.

The political side of action research involves action research using the partnership forged between the researcher and research participants to initiate change and resolve a problem within a given community. This distinct quality differentiates action research from other research strategies. It is at this point that action research transcends the academic realm of research methodology and encroaches onto the socio-political realm. It is more than just research and becomes a transformative tool. This transformation can take place at the most basic/grassroots level of society or business and even at the national level. Miller et al. (2003:11) add that action research brings together theory and practice, researchers and participants. She adds that action research challenges unjust and undemocratic economic, social and political systems and practices. Greenwood and Levin (2007:03) label action research as a collaborative and democratic strategy of generating knowledge and designing action through the researcher and the local stakeholder. Kemmis et al. (2010:424) weigh in and equate action research to a democratic dialogue between the researcher and participants. They state that action research provides an alternative relationship between the researcher and participants. Huang (2010:99) states that action research aims to empower those research participants in oppressive contexts where they are marginalised. The contexts could be communal, provincial, national, or even organisational.

5.1 Characteristics of action research

The key characteristics of action research include a partnership between the researcher and the research participants. Thereafter, there are four stages which are used to conduct action research. These stages are:

- Diagnostic stage

- Action plan

- Intervention

- Evaluating.

Saunders et al. (2009:147) state that the problem is diagnosed, a plan of action is devised, the plan is implemented, and then the outcomes are evaluated to decide as to whether they resolve the problem identified earlier. It is important to note that unlike other research methods, action research is cyclical. This means that the research process can end and resume if the action taken did not bring about the desired change.

5.2 Limitations

Scholars such as Miller et al. (2003:18) have criticised action research because it is often done on a small scale. Furthermore, its findings cannot be replicated in another context, as with positivist or experimental types of research. They add that action research is most suitable for local issues and not bigger national issues. Of equal if not more importance, various critics of action research seem to indicate that it assumes that the authorities of all communities embrace democracy and participation. As stated earlier, Huang (2003:99) argued that action research aims to emancipate stakeholders in oppressive contexts. However, considering the political landscape in some developing world contexts such as in Africa, action research is not entirely suitable. It may put both the researcher and the research participants at risk. This is because the political systems in some of these contexts do not support the concept of community members participating to bring about change. In such contexts, the leaders can easily construe action research as a direct threat to their power.

One such context is Zimbabwe, where the government, especially under the Mugabe administration (1980–2017), was highly suspicious of any non-governmental or community-based organisations. This is a well-documented fact which I noted in my 2016 publication Citizen engagement and local governments in Zimbabwe: The case of the Mutare City Council.

I argued that the government was not very receptive to the idea of citizen participation or democracy and accused its proponents as agents of a regime change agenda. This considered, the government then crafted legal instruments which restricted activities that tried to instil a spirit of participation, change and democracy among Zimbabweans. These legal instruments included the Private and Voluntary Organizations Act of 1996 and the NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) Act of 2004 (Muchanyuka 2016:110). It is also important to note that these components, which are unwelcome to the government, are the key components of action research. Such a political landscape is not unique to Zimbabwe but exists in many other parts of Africa. However, I am not going to delve more deeply into this issue as these challenges have been documented and deliberated at length by other scholars. These scholars include Dambisa Moyo, author of Dead Aid (2009) and Alex Thomson, author of An introduction to African politics (2010), among others.

Despite the risks related to action research in Zimbabwe, I proceeded with caution and was transparent with authorities at all levels of the hierarchy – traditional, local and provincial – to mitigate suspicions of my intentions.

6. Findings

Phase 1: Diagnostics

A pattern of recurring violence has been recognised in communities along the Zimbabwean border with Mozambique. Furthermore, a lack of sustainable violence-reduction measures have also been noted. This would appear to indicate a lack of capacity and will on the part of the Zimbabwean government to address the violence. This then led to the idea that if the community was capacitated with its own violence-reduction measures, it could implement them on its own. The Chipinge-East Constituency was identified as the area most affected by the RENAMO violence and hence the research was located in that area.

Phase 2: Action plan

Following the diagnostics, the local and traditional authorities were approached and the concept of LPCs was introduced. The authorities were receptive to the idea and an action plan was then drafted in consultation with them. The action plan involved gathering a group of community members from various parts of the constituency and training them to use LPCs and EWER (Early Warning Early Response). Thereafter, this group would then be formalised as the Chipinge-East LPC, with a chairperson, deputy, secretary and other relevant positions. This LPC would then be guided into establishing its own tools of violence reduction through EWER. These tools would include a community safety action plan, a contacts list, an EWER matrix and an EWER plan suited to their specific context. These tools would then be presented back to the local authorities and different parts of the Chipinge-East constituency.

Phase 3: Intervention

The Chipinge-East community training was divided into two: LPC and EWER training. The selection of the training was based on the information gathered from the research participants concerning the nature of the violence they have endured and the initiatives which have been undertaken by their community and the Government of Zimbabwe. The main objective of the training was to equip the Chipinge-East community members with the capacity to take initiatives to protect themselves from RENAMO violence. The training was meant to make them see the importance of taking the initiative as a community – and not always having to rely on government institutions to protect from violence. These suggestions were offered given the state’s repeated failure to protect the Chipinge-East community members from RENAMO violence. Most of the villages affected by the violence are in remote areas, far from the emergency and security services located in the Chipinge urban area. Accessibility to these communities is also a challenge given the deplorable state of the roads in the area and the mountainous terrain of the Chipinge District. The distance between the town of Chipinge and Gwenzi Village in Chipinge-East is 66 km. However, owing to the bad state of the roads, the journey took me close to two hours on a good day. Therefore, any rescue mission dispatched to these communities took a long time to reach them. Furthermore, the trainings were done due to the community’s fear of initiating peacebuilding initiatives to resolve the violence in their community. The LPC training was meant to allay this fear by equipping community members with skills to take the initiative, and was meant to suggest their right to do so.

7. Discussion

LPC training

The training was conducted over two days from 3–4 January 2019, with members of various Village Development Committees (VIDCOs) in Chipinge-East Constituency. The training venue was the homestead of the Gwenzi Village chief in the same constituency. Fourteen community members attended the training. Some of these members had been involved in the focus group discussions and key informant interviews which took place between June and December 2018. Four of the participants were female and ten were male. The participants were selected through an open invitation sent to community members by the local authorities. The participants in the training were also drawn from various professions in the Chipinge-East community, such as health, education, law enforcement, farmers, local authorities and traditional leaders. The first day of the training dealt with the basic concepts of peace and conflict, while the second day was dedicated entirely to LPCs.

Prior to the training, the participants wrote a pre-test involving nine questions. The questions examined their understanding of the basic concepts of peace and conflict, including positive peace, negative peace, peacebuilding, conflict, conflict management, conflict resolution, and conflict transformation – as well as what the community understood by the term ‘local peace committee’. The questions were meant to gauge the participants’ knowledge of peace and conflict theories and the methods to build peace. It is often assumed that people are familiar with what peace and conflict entails, but their responses in the pre-test showed that their knowledge was scanty.

The training programme was thus influenced by the results of the pre-test. Instead of primarily focusing on LPCs, the training began with sessions on the basic concepts of peace and conflict. Regarding the LPCs, the training focused on their origins and typology, along with a few case studies on some of the LPCs that have managed to address the challenges faced in their respective communities. The case studies included the Wajir Peace and Development Committee (WPDC) in Kenya, the Collaborative in South Kordofan in Sudan, and the Barza Communautaire in the North Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The training used various methods of learning, and was mainly participatory. Participants were all given an equal opportunity to share their views, experiences and opinions. This assumed that each of the participants had information to share. Dramatisations were used at times to illustrate certain aspects of the training, such as the different methods of conflict resolution.

Following the training, a post-test was conducted to check whether the participants fully understood basic concepts of LPCs, peace and conflict. The post-test showed that most participants had increased their knowledge in terms of LPCs and EWER. Furthermore, they shared feedback of their experiences during the course of the training and indicated that it was their first experience with such information and that they had become enlightened on how best to face the violence that was bedevilling their community.

EWER training

The training was conducted from 11–12 February 2019 at the same venue and with the participants who had done the LPC training the previous month. Ideally, an LPC would engage with the perpetrator of the violence – the RENAMO rebels. However, during a key informant interview, the Manicaland Provincial Administrator stated that this was impossible considering the peculiarity of the situation. He noted that although the Chipinge community was very near Mozambique, engagement would have to occur at inter-governmental levels through the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Any local dialogue would require permission from these levels. In addition, there was a security risk if the Chipinge community members engaged the rebels, which was heightened by the unpredictable nature of the rebels themselves. Considering these factors, I decided to equip the community members with skills that could help them to predict and protect themselves from the onset of violence. This is how the idea of early warning systems emerged.

As in the previous training, various methods were employed to conduct the training. These methods included simulations, role-playing, group discussions, and presentations. Simulations were used to illustrate how the community could use early-warning systems in the event of an attack on the community. Mock drills were used for this. Group discussions were used to discuss the hot spots for attacks, to plan for the vulnerable members of the community, and to identify safe routes. The different teams would then present their findings to the larger group and obtain instant feedback and recommendations on their presentation. This method of group discussions was meant to engender a spirit of initiative and cooperation among the community members. Through the discussions and presentations, the community members gained confidence in themselves.

The two-day training was divided into two parts. The first part focused on the early warning systems that could be implemented to predict the onset of violence or danger to a community. This session included topics such as rumour monitoring, community maps with markings of safety spaces, assembly points and hot spots for the attacks on the community. The second part discussed early response strategies which the community could use in the event of violence. These methods included contact lists, quick run bags, communication trees, and planning for the vulnerable members of the community. These concepts were explained and discussed as follows:

EWER was defined as a broad-based and multi-faceted strategy that strives to ensure the safety of the entire community in times of danger. Danger encompasses various threats and disasters such as man-made and natural disasters. However, in the case of Chipinge, the EWER mainly focused on the violence resulting from the RENAMO incursions.

Rumour monitoring: Before passing on information to their leaders or neighbours, the community members applied triangulation and verified the information which they gathered from the mainstream or social media, or from their friends and relatives in Mozambique. The importance of monitoring at this point was to avoid the spread of misinformation as it renders the EWER system unreliable. Together with the participants, various ways to triangulate information were explored. It was agreed that should any community member receive any information pertaining to oncoming violence from the RENAMO rebels, they should crosscheck the information with either community leaders or the mainstream media. It was agreed that social media was an unreliable source of information. To this end, the participants stated that it was important to keep abreast of the political developments in Mozambique through two methods. The first method was listening to radio broadcasts from both countries, for example, the Zimbabwean Diamond FM radio or radio Espungabeira from the Mozambican side. The second method involved regularly communicating with friends and relatives from Mozambique. The participants agreed that the opportune moment to do this was during a monthly event called Kwa 2. This monthly gathering occurs when Mozambican and Zimbabwean traders meet every second day of every month to trade their wares without any customs restrictions.

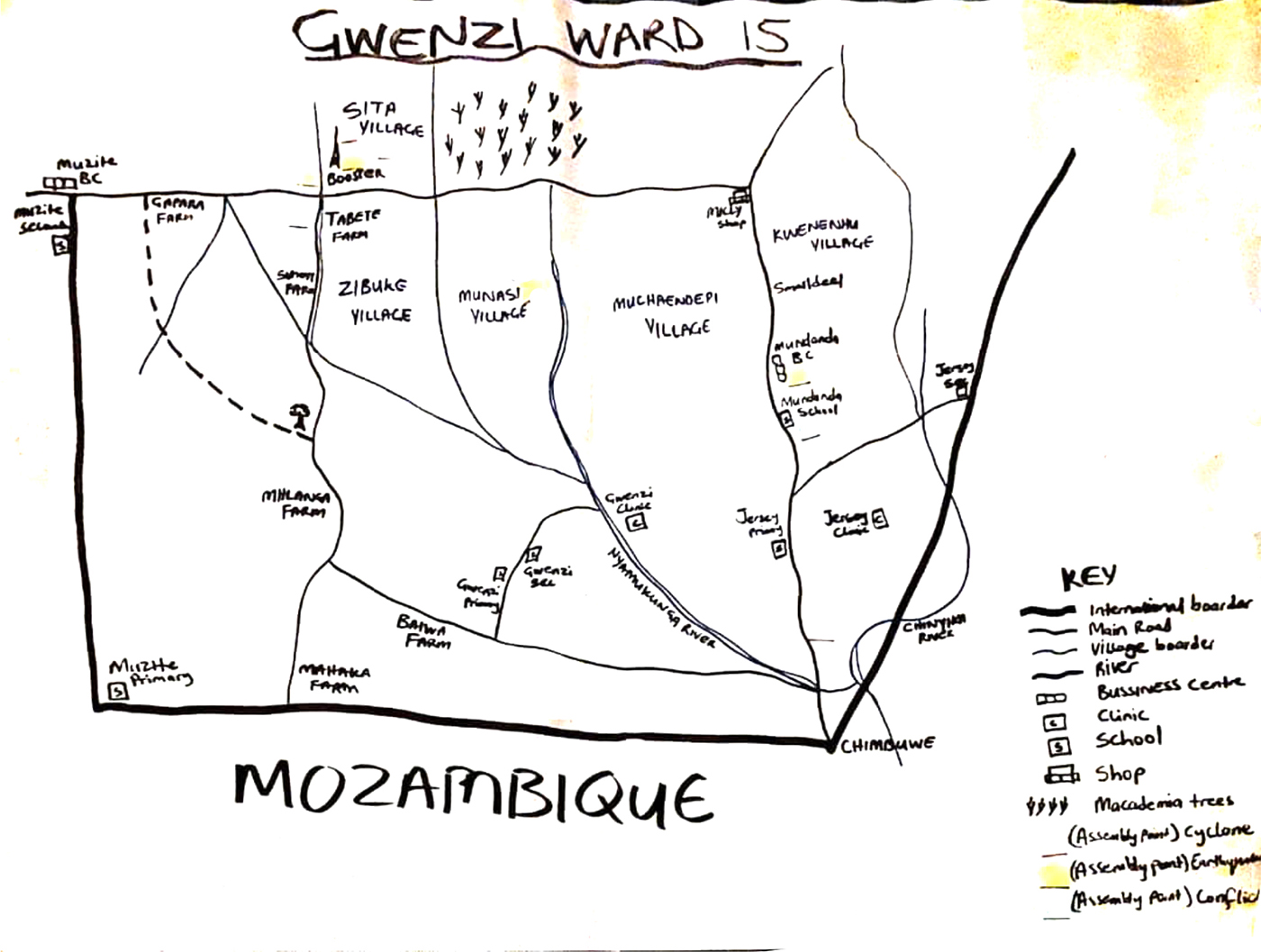

Community maps: Refers to a diagram which the participants had to draw using their knowledge of their community and its history in respect of the violence from RENAMO rebels. The diagram indicates the hot spots of these attacks and the safe routes to be taken by the community members when wanting to reach assembly points.

Communication structures: Involves the channels which the community members had to use in the event of an outbreak of violence. Community members developed a list of emergency services that could assist them in the event of an attack – for example, police, army, hospitals, and clinics. In addition, the community members had to develop their own contact lists in their respective neighbourhoods.

Emergency kits: These are bags kept ready at all times. The bag contained essentials to be used by the community members if they had to evacuate their homes because of the onset of violence. During the training, the fact that the contents of the bag differed depending on the person carrying the bag was discussed. The contents of the bag of a lactating mother would be different from the bag of an elderly woman. However, generally, the contents of the bag included food, medical supplies, identification documents and toiletries, among other things.

Plan for persons with specific needs: The community members had to develop a plan for the vulnerable members of their community. ‘Vulnerable members’ refers to those people with a diminished capacity to defend themselves from the violence of the rebels. These persons include children, the elderly, the disabled, and pregnant and lactating mothers. The plan was to include how such members were to be protected and how their special needs were to be catered for during episodes of violence.

The EWER training differed from the LPC training in that it relied more on the contextual knowledge of the participants. The participants had lived in the Chipinge-East community for the most of their lives and some of them had experienced the violence that the community endured at the hands of the RENAMO rebels. Through this knowledge, the participants already knew about the hot spots, the safe routes, the vulnerable members of the community and the communication tree. The training was more of a facilitation for the community to discuss this knowledge and to bring it into an integrated early warning response plan.

8. Establishment of the Chipinge-East LPC

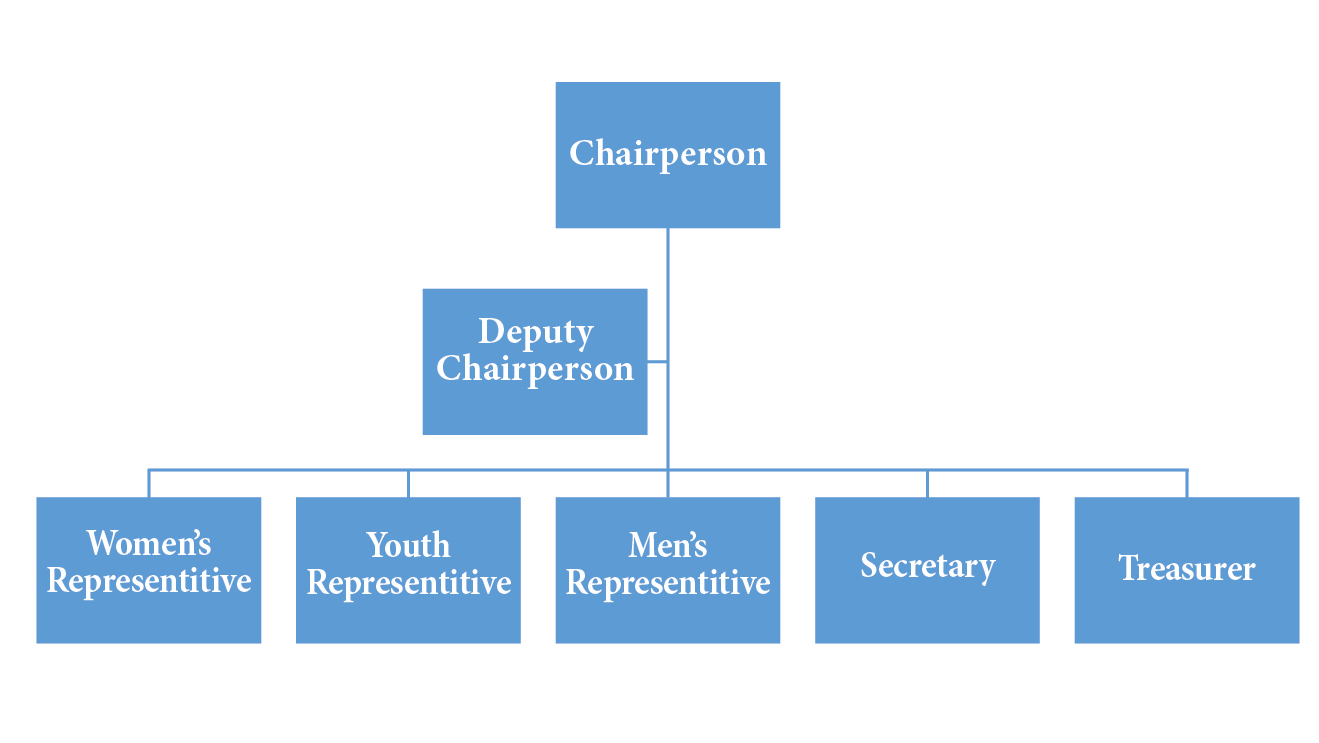

After the first training on LPCs, the participants formed the Chipinge-East LPC. The participants elected various members to fill the positions on the LPC: chairperson, deputy chairperson, women’s representative, youth representative, and men’s representative – as illustrated in Figure 1. The committee, whose members represented the diverse interests of the different groups of people involved, was charged with discussing ways to better prepare the community for RENAMO violence. The LPC was self-funded in the interests of self-sufficiency and to minimise interference from external parties.

Figure 1: Membership of the Chipinge-East Local Peace Committee

8.1 The Chipinge-East EWER strategy

After the formation of the LPC, the LPC members resolved to develop their own EWER strategy based on the Chipinge context, which would be shared widely with the rest of the Chipinge-East community. This exercise raised awareness of the dangers which the community members may face and what they could do in the event of an attack from RENAMO rebels. Through a series of meetings after the training, the LPC members formulated the Chipinge East EWER strategy. The strategy was documented and developed into flyers that were to be widely distributed to the wider Chipinge community. The flyers included a contacts list, an EWER matrix, an EWER contingency plan, and a community map. Where possible, the flyers were translated into Shona to assist with the comprehension of the message by all community members.

The contacts list included the numbers of the local authorities and rescue services, which the affected community members could call upon in the event of an attack. For instance, the chief, police, hospital, Member of Parliament, and District Administrator (DA) – as illustrated in Figure 2 below. However, some LPC members felt that some community members could abuse the contact information on the list. The LPC agreed with this point and resolved that the contacts list would not be given to all community members and would not be developed into posters for public places. Rather, the contacts list would be shared with heads of departments, local authorities and traditional leaders, who were all expected to be more responsible with the information and to use only when necessary.

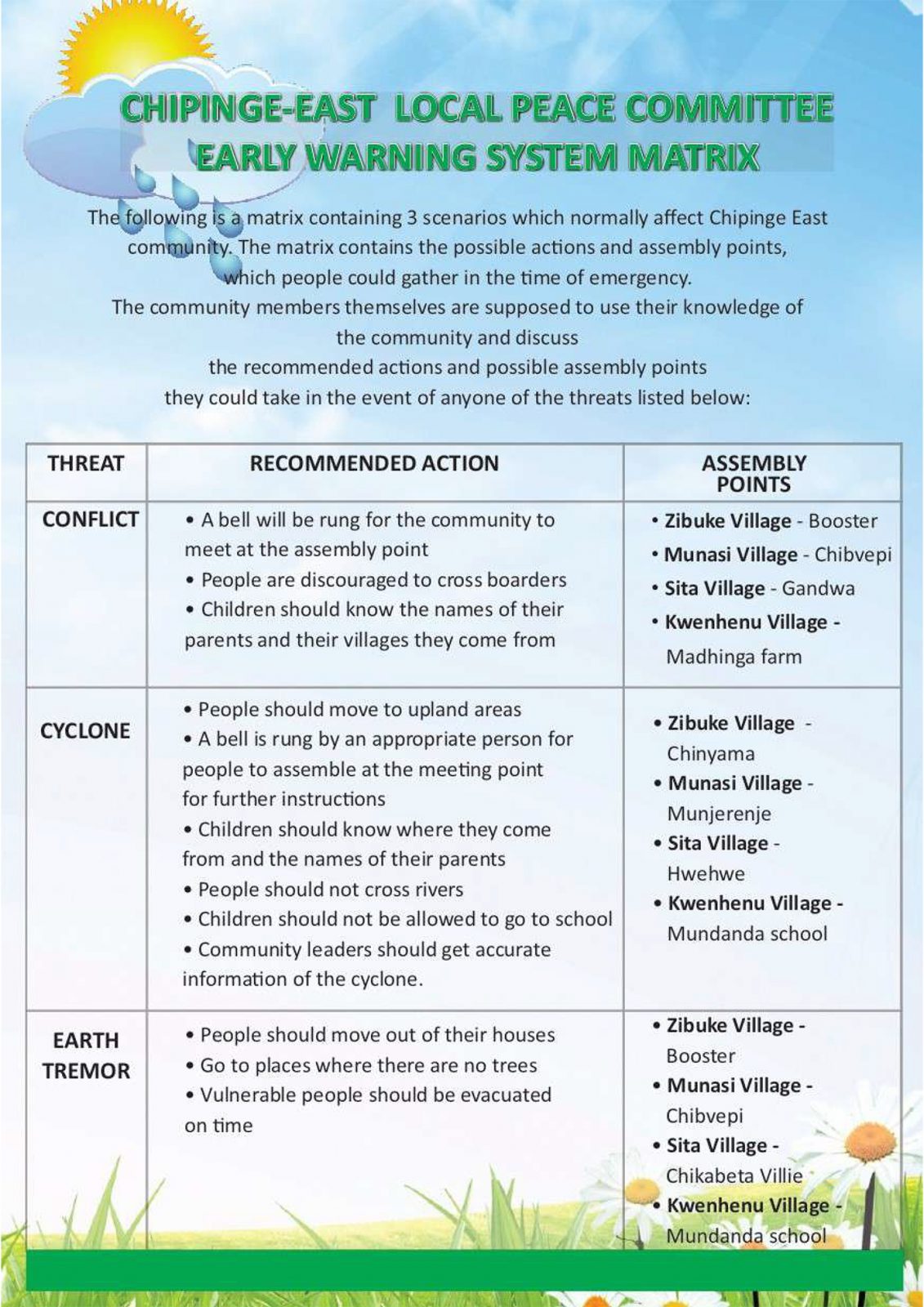

In addition to the contact lists, the training participants devised an EWER matrix. The matrix listed the threats which the community faced, and the response mechanism which the community could use to mitigate the effects of these threats. From the discussions, it emerged that the community was not only affected by the RENAMO violence but also by meteorological natural disasters, such as cyclones and earth tremors. The participants also went on to identify possible responses to these threats. On the threat of RENAMO violence, the participants recommended action was for the community to gather at assembly points and to carry an emergency kit in the event of a displacement. Furthermore, the community identified possible assembly points for the different villages – Zibuke, Munasi, Sita and Kwenhenu – as illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 2. Chipinge-East LPC list of contacts

Figure 3: EWER matrix

Figure 4: Chipinge-East LPC Early Warning System (EWS)

The participants also devised a wider strategy to use during attacks. This was to encourage the setting up of LPCs in other communities, which faced a similar threat. The strategy had a series of steps that included the provision of a contingency plan, communication structures, plans for the vulnerable members of the community, rumour monitoring and the contents of an emergency kit. The participants drew a community map (see figure 5 below) of one of the locations that was most affected by the RENAMO attacks. The map was drawn in order to identify and mark the hot spots of the attacks and the different assembly points to which the community members could rush to in the event of an attack or any other emergency.

There was however concern that the information could fall into the hands of the rebels.

Figure 5: Assembly points map

8.2 Awareness-raising sessions

After the development of these flyers, the LPC members divided themselves into two teams to deliver the flyers to the wider community. Besides raising the awareness of the action plan in the event of an attack, this move would also encourage the ownership of the formulated strategy by community members. The flyers of the early warning matrix and contingency plan were widely distributed to surrounding villages and even schools. The early warning matrix and the contingency plan flyers were printed on size A3 posters, which were stuck on/in surrounding public places, such as shops, hospitals, clinics, and farms. The LPC members also took time to explain the contents of these flyers to the members of the public – for instance, school children and farmers as shown in table 1 below:

Table 1: Chipinge-East Awareness Raising Sessions

| Location | Date | Number of people |

| Mundanda small-scale farmers | 26/04/2019 | 70 farmers |

| Kwenhenu Village | 27/04/2019 | 87 HH (Households) |

| Gwenzi small-scale farmers | 30/04/2019 | 25 farmers |

| Mzite Primary School | 09/05/2019 | 2 000 pupils |

| Sita Village | 12/05/2019 | 52 HH |

| Munasi Village | 12/05/2019 | 62 HH |

| Zibuke Village | 12/05/2019 | 55 HH |

| Gwenzi Secondary School | 13/05/ 2019 | 331 students |

9. Evaluation by stakeholders

9.1 Feedback workshops

After the formulation and presentation of the EWER strategy to the wider Chipinge community, it was time to present it to the local authorities and government officials at district and provincial levels. The fact that the Chipinge East LPC already had traditional leaders from the area made it easier. The feedback workshops were an important step for two reasons. The first was that considering the sensitivity of the government to community initiatives, it was prudent to keep the government officials appraised of every step made by the Chipinge-East LPC. This would limit any suspicions harboured by government officials in respect of community initiatives. After consulting case studies of LPCs in different parts of the world, I concluded that tensions with the government arise from the misconception that the LPC wants to replace the government or local authorities. This misconception arises when the government and local authorities are informed about LPC activities.

Second, the LPC wanted the support of the government to address issues of violence along the border. The support of the government and the local officials was essential to the success of the LPC and its activities. While the government and local authorities are part of the problem which led to the establishment of the LPC, they are also part of the solution. It is undeniable that the government has powers which can be used to block or support the activities of the LPC. Having the support of the government and local authorities also makes it possible for the LPCs to be developed in other parts of the country facing similar challenges. This is not to say that the government should be actively involved in the day-to-day running of the LPC, which has been proven to be a bad idea elsewhere – for example, the case of the Barza Communitaire LPC in North Kivu and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Rather, the LPC and the government should maintain lines of communication, but carefully maintain their distance. This is the cosmopolitan approach to the running of LPCs advocated by Kristoffer (2009).

At all stages of the research, I kept the local authorities and government officials updated on what the research was about and how it was progressing. I met with the Provincial Administrator (PA), the Chipinge District Administrator (DA), the Chipinge East Member of Parliament (MP) and the traditional chiefs of the villages that participated in the research. To these officials, I presented the letters of research from DUT (Durban University of Technology) and briefly explained the nature of the research. This was done to ensure that there was no confusion about the research and the LPC. It was thus now only fair to inform them of the research study outcomes. This willingness to share information was important to impart to the LPC – to ensure its very survival in the Zimbabwean political environment.

9.2 District level

Following the research, formation of the LPC and the formulation of its strategies and their subsequent implementation, the first feedback session was held at district level on 11 July 2019. The venue of the session was the Chipinge Government Complex in the District Administrator’s boardroom. Twenty stakeholders from various government departments, the NGO sector, and the media were invited to the session. Due to the prohibitive transport costs, the Chipinge LPC chose three members (two males and one female) to present in the session on their behalf.

The DA and his assistant attended. The DA made opening remarks, I took over and briefly described the origins of the research, the reasons behind it and the methodology used. The three LPC members then presented the challenges they faced in their community at the hands of the RENAMO rebels. They then presented the EWER strategy they had formulated as a community to counter the RENAMO violence. They shared the fliers of the contacts list, the EWER system, and the EWER matrix. The stakeholders were then given time to react to the presentation through questions, suggestions and constructive criticism.

The EWER strategy was well received by the stakeholders at district level. The DA urged the Red Cross, which was represented at the session, to support the EWER strategy and to promote it to all the wards of Chipinge: 30 rural and 8 urban. He bemoaned the lack of preparedness for the threats which faced the community, giving as an example the fire extinguishers in the building which were last serviced in 1997. Other stakeholders also made suggestions which could help strengthen the EWER strategy. It was suggested that toilets should be placed at the designated assembly points to avoid disease spread when people assemble there. The LPC was urged to ensure that community members sleep with their phones switched on in case of emergencies. The stakeholders implored leaders to be more responsive to alerts brought to their attention by community members. The chiefs in the session in turn urged community members not to fear their traditional leaders – chiefs and the headmen – but to feel free to approach them with information or concerns. It was also recommended that emergency kits should be accessible to all members of the household, especially children. All members of the household should know where the bag is kept in case of emergencies. The officials representing various media houses were impressed by the presentation of the EWER strategy and reporters from Diamond FM, Manicaland’s premier radio station, interviewed the LPC representatives at length.

The session ended with the DA urging the LPC representatives to reach out to other communities in the Chipinge District and to set up other LPCs. All this demonstrated that keeping the local authorities informed about the activities of the LPC had been fruitful in the form of a cordial reception and its possible expansion to other areas.

Some of the recommendations were implemented to strengthen the LPC and the EWER strategy. The recommendations undertaken were those that did not require any financial input and were under the control of the LPC. Examples of these recommendations include the accessibility of the chiefs to the wider community, and awareness of all household members of the location of emergency kit. The suggestion of building ablution facilities will need assistance from local authorities.

9.3 Provincial level

The session was held on 16 July 2019 at the Mutare Government Complex in the Minister of State’s boardroom. Twenty-three stakeholders were drawn from various professions, such as the army, the police, and government departments. The media were not invited to the session and the Minister of State failed to attend because of an emergency meeting that had to be held in Harare. However, the Provincial Administrator (PA) managed to attend on behalf of the Minister.

The session progressed in a similar manner to the one held at the district level in Chipinge. The PA made some opening remarks. I then continued and explained the research background and methodology. The representatives from the Chipinge East LPC presented the EWER strategy they had formulated. Thereafter, the stakeholders were given an opportunity to analyse the EWER strategy.

The PA welcomed the idea of the EWER made by the Chipinge East LPC and the progress it had made. He noted that it was easier to work with empowered communities such as the Chipinge East LPC. He urged the LPC to spread its activities to areas such as Beacon, which faces the challenges of earthquakes. It was noted that assembly points should be selected with the assistance of geophysical experts, to avoid assembling at unsafe locations. The stakeholders also cautioned against excessive reliance on social media. The PA suggested the distribution of walkie-talkie radios to all community members, because during periods of violence the cellular base stations may not be functional. He noted that the government had begun doing this in the aftermath of the Cyclone Idai in March 2019. However, there were some reservations about the LPC EWER strategy. One stakeholder stated that given the current peaceful relations along the border with Mozambique, there was no need for such a strategy. The PA stated that the government was working effectively with the VIDCOs (Village Development Committees) and WADCOs (Ward Development Committees) – adding that the planning process in Zimbabwe is always bottom-up.

These statements made me realise that the officials were oblivious of the situation on the ground. In light of this situation, I felt it necessary to inform them that the situation I discovered in the local area was entirely different. I took the time to clarify what I took to be misconceptions. Regarding the current peace along the Zimbabwe–Mozambique border, I noted the unpredictable activities of the RENAMO rebels. The chances of the violence continuing are high, considering the flaws of the Rome Peace Agreement of 1992 and the prevailing skewed political environment in Mozambique – as noted by scholars such as Muchemwa and Harris (2018).

The chances of violence are also heightened considering the split in the RENAMO forces and the rejection of the August 2019 Peace agreement by a new faction of the RENAMO rebels, calling itself the Military Junta under the leadership of Mariano Nhongo. Furthermore, the election violence that occurred in Mozambique before and after the 15 October 2019 presidential and provincial elections proved this point. I added that peacebuilding had transitioned from being largely reactionary and concerned with post-conflict reconstruction, to a violence-prevention emphasis. It also encompasses more activities than just dialogue between the conflicting parties.

9.4 Reflection on the intervention

On reflection after the session, I realised several things. The Chipinge-East LPC and its EWER strategy were welcomed more warmly at the district level in Chipinge than at the provincial level. I attributed this to the fact that the district was more in tune with what was happening on the ground. The provincial stakeholders are located almost 200 km away in Mutare, the capital of the Manicaland province, and were thus far removed from the reality in Chipinge District. In addition, the feedback session came at a time when the provincial government was dealing with the aftermath of Cyclone Idai that had struck the province barely four months before. Thus, the provincial government was preoccupied with the Cyclone Idai aftermath, and RENAMO rebels were a secondary issue.

Stakeholders responses which discouraged the existence of the LPC, also indicated that the understanding of peacebuilding among government officials as a violence-prevention method is yet to take root. This came as no surprise considering the history of the Zimbabwean government in relation to peace issues. Previous reactions to conflict showed that the government is more inclined to reactionary measures in dealing with the RENAMO violence. It also suggests that the provincial government is not closely monitoring political developments in Mozambique. This again suggests that the communities along the border need to take matters of RENAMO violence into their own hands. It also reveals that the concept of LPCs is still in its infancy in Zimbabwe. The government and other stakeholders are yet to comprehend fully the purpose of the LPCs and their potential in addressing some of the issues facing communities.

Despite the discouragement arising from the provincial session, I was not deterred. Rather, it was a reminder of how much work still needs to be done in order to make stakeholders more accepting of the LPC concept. My research alone was not enough to address the issues between the government structures in Zimbabwe and community initiatives such as LPCS. The session indicated that keeping the government officials and local authorities informed about the activities of the LPC may be insufficient. Capacity building is also needed for government officials and local authorities, especially relating to the concepts of peacebuilding, LPCs, and EWERs.

10. Conclusion

The research demonstrated that through LPCs, communities at risk of RENAMO incursions along the Zimbabwe–Mozambique border can successfully formulate and adopt violence-reduction strategies. These strategies include EWER matrices, contact lists and community safety maps. To avoid dependency, the LPCs need to finance themselves and remain independent of any government influence. However, for LPCs to succeed they need the community to coordinate with local authorities to avoid misunderstandings. Furthermore, the research demonstrates that there is still a need for the concept of LPCs to be understood and embraced at national level. The government needs to be open to the idea of LPCs and not to see them as a threat, but rather as a bridge leading to conflict transformation and positive peace in Zimbabwe.

Sources

Ayodele, Samuel M. and Oseremen I. Felix 2017. Infrastructure for peace: The African experience. African Research Review: An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 11 (2), pp. 26–38.

Dube, Donwell and David Makwerere 2012. Zimbabwe: Towards a comprehensive peace infrastructure. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2 (18), pp. 297–307.

Greenwood, Davydd J. and Morten Levin 2007. Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. 2ed. Sacramento Sage.

Huang, Bradbury H. 2010. What is good action research? Action Research Journal, 8 (1), pp. 93–109.

Irene, Oseremen 2014. Building infrastructures for peace: An action research project in Nigeria. PhD dissertation, Durban University of Technology.

Issifu, Karim A. 2016. Local peace committees in Africa: The unseen role in conflict resolution and peacebuilding. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 09 (01), pp. 141–153.

Kemmis, Stepen, Robin McTaggart and Rhonda Nixon 2010. The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Ontario, Springer.

Kristoffer, Liden 2009. Building peace between local global politics: The cosmopolitan ethics of liberal peacebuilding. International Peacekeeping, 16 (5), pp. 616–634. Miller, Mary, B., Davydd Greenwood and Patricia Maguire 2003. Why action research? Action Research Journal, 1 (1), pp. 9–28.

Moyo, Dambisa 2009. Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa.

New York, FSG Books.

Muchanyuka, Muneyi 2016. Citizen engagement and local governance in Zimbabwe: A case study of the Mutare City Council. Amity Journal of Management Research, 1 (2), pp. 103–122.

Muchemwa, Cyprian 2015. Building friendships between Shona and Ndebele ethnic groups in Zimbabwe. PhD thesis, Durban University of Technology.

Saunders, Mark, Phillip Lewis and Adrian Thornhill 2009. Research methods for business students. 5ed. New York, Pitman Publishing.

Thomson, Alex 2010. An introduction to African politics. 3ed. London, Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Tongeren, Paul van 2012. Infrastructures of peace. In: Bartoli, Andrea, Zacharia Mampilly and Susan Allen. eds. Peacemaking: From practice to theory. Kiev, abc-clio. pp. 400–419.

Tongeren, Paul van 2013a. Background paper on infrastructure for peace, Seminar on Infrastructure for Peace, Part of 6th GAMIP Summit in Geneva, Switzerland.

Tongeren, Paul van 2013b. Potential cornerstone of infrastructure for peace? How local peace committees can make a difference. Peacebuilding, 1 (1), pp. 39–60.