Abstract

One chieftaincy conflict that has engaged the attention of all governments of Ghana since independence has been the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis. An ex-post analysis of the latest state of mediation and intervention efforts to resolve the crisis since the March 2002 eruption of bloody conflict, highlights a political stalemate that has challenged mediator intervention strategies. The Committee of Eminent Chiefs (CEC) appointed to mediate the dispute was stalled from 2009 until November 2018, when the Committee laid out a road map for peace which culminated in the installation of Ya Na Abubakar Mahama Andani. The approaches span 17 years of dealing with the crises – given several weaknesses associated with the resolution regimes. Adopting ethnographic and other qualitative methods of data collection, this article posits that, in spite of the inveterate tendency to resolve traditional political problems through modern democratic systems, the Dagbon crisis could have been resolved as a state-brokered intervention by adopting a modern electoral college system grounded in a ‘Clean Sheet Redesign process’ to pave the way for the restoration of the Andanis and Abudus family gate rotational system.

1. Introduction

A key characteristic of citizenship is the inalienable right to determine directly or indirectly who governs in a defined jurisdiction over a particular period of time, in accordance with legal frameworks that regulate the succession process in the political system. The processes of choosing the appropriate candidate for dynastic occupation resulted from historical precedents that regularly yield to the legitimacy of the people. Traditional systems in Africa developed various forms of legitimate leadership during pre-colonial periods, which remained operative through the transition from the colonial era to the modern state. This persistence became a moral claim during the colonial period and was used by the nationalist movements. Jackson and Roseberg (1984:178) maintain that nationalists used the quest for legitimacy as a basis and effective tool for engagement with colonial administrations in independence struggles. In traditional African societies, political systems are shaped by the nature and the type of society. For example: acephalous societies are governed by unstructured political systems, while centralised societies use more hierarchical political systems. In Ghana, while acephalous societies are mostly patrilineal, centralised structured political systems vary between the matrilineal and patrilineal systems of inheritance.

According to Almond and Coleman (1960), a political system is the system of interactions found in all independent societies, which performs the functions of integration and adaptation by legitimate physical compulsion. Scott and Mcloughlin (2014) conceptualise political systems as formal and informal political processes by which decisions are made concerning the use, production and distribution of resources in any given society. Formal political institutions can determine the process of electing leaders, the roles and responsibilities of the executive and legislature, the organisation of political representation, and the means for accountability and oversight of the state. In formal and customary political systems, norms and rules can operate within or alongside these formal political institutions. Furthermore, Almond and Coleman (1960) identify three main functions of a political system: (1) to maintain integration of society by determining norms; (2) to adapt and change elements of social, economic and religious systems that are necessary for achieving collective political goals; and (3) to protect the integrity of the political system from outside threats.

As an aspect of the political system of succession, Andreas (2012) postulates that inheritance customs do not follow clear ethnic, linguistic or geographical patterns. Equality between all sons and a subordinate position of women, with the exclusion of daughters from inheriting, are prominent aspects of Hungarian, Albanian and most Slavic societies (Andreas 2012). He notes that the regulation of property inheritance and the status of succession are a primary function of kinship structures in bilateral societies, including contemporary Western nations. On the contrary, inheritance rules in unilineal systems specify that status and property be passed exclusively through male or female descent lines, usually in the context of a corporate group control of collectively owned land and other assets.

Boston’s (2011:707) submission on inheritance in political systems can largely be associated with the monarchical systems in Europe, Asia and Africa, which draw their succession from primogeniture in which the elder son or daughter succeeds the reigning monarch. This system is practised in Spain, Monaco and Saudi Arabia. Berg-Schlosser (1984) argues that the traditional political system of most African countries ruled by chiefdoms and kingdoms also follows this line of succession. Similarly, Alston and Schapiro (1984) further state that inheritance transfers are divided into two principal types: primogeniture (passing on all wealth and status to the elder son), and multigeniture (dividing the wealth among all the sons or children). Inheritance transfers can also be by partibility (dividing the land among the children) which is associated with multigeniture and impartibility (keeping the land as a single piece), which is associated with primogeniture. It is quite widely acknowledged that in many African societies, inheritance systems have corresponded with patrilineal or matrilineal descent principles. In patrilineal cultures, children are primarily considered members of their father’s kin group and inherit the father’s property at his death. In matrilineal cultures, however, kin membership is traced through the mother’s line, so that children belong to their mother’s kinship (matrikin) and not to their father’s kinship. In this respect, a man’s heirs are his sister’s children, and not his own (Cooper, 2008).

2. Successions and political conflicts

According to Ojo (2007), political succession is the transfer of political power from one group to another. The degree of orderliness within this transfer is assessed as evidence of maturity on the part of the political system. Moreover, in the international sphere, the degree of orderliness is the accepted barometer for assessing both the consolidation and the quality of democracy in a polity at any particular point (Diamond and Morlino 2004:20–31).

In regular succession, a leader’s entry or exit occurs through explicit rules or established conventions, such as direct election in democracies, hereditary succession in monarchies, designation of a successor by a dictator, by party rules such as in the Chinese Communist Party, and many other routes. However, in cases of irregular successions, Inman (2014) notes that a leader’s entry or exit does not occur through explicit rules or established conventions. This often occurs in the cases of military coups, rebellions and assassinations. Furthermore, Obodumu (1992) contends that a discussion of succession in Africa “has the tendency to instantly direct academic imagination to the backward phenomenon of violent and unconstitutional overthrow of governments.”

In the local and traditional contexts, others such as Prah and Yeboah (2011) reiterate the factors responsible for conflicts arising out of political succession in their discussion on chieftaincy disputes. They postulate that chieftaincy conflicts can result from several factors, including disputes over rightful succession to stools or skins, control over stool lands and land litigation, political interference, inordinate ambition for power, and the lack of accountability and transparency of some traditional rulers (Prah and Yeboah, 2011:23).

3. The cost of conflict and problems of succession

The central argument of this article promotes the adoption of the electoral college system as an alternative mechanism to resolve the Dagbon chieftaincy wrangling that has plagued the two families concerned since 1954. A solution would be to select one family to occupy the skin and to pave the way for the rotational system to recommence.

The objectives of this article are to assess the institution of kingmakers in Dagbon, and to use a Clean Sheet Redesign notion to present a final solution to the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis. In order to contextualise the matter, the article will explain the customs relating to the establishment of kingmakers and a Council of Kingmakers, and will also explain the rules governing the eligibility and responsibility of kingmakers.

The Dagbon chieftaincy crisis has plagued successive colonial and post-independent administrations until now. The primary actors of the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis are the Abudu and Andani clans, both of whom claim legitimacy in the selection of the Ya-Na, the king of the Dagomba people and of the Dagbon state. One of the underlying factors responsible for the crisis is the selection procedure for the Ya-Na and the institutions which are assigned this responsibility (Tonah 2012).

Throughout the crisis, the crux of the matter lies in what should be the most accurate method of succession. The misunderstandings between the Abudu and the Andani families over this precarious process have contributed to the cycle of disputes about this chieftaincy. Throughout the conflict, all administrations from colonial times to Akufo-Addo (2019) have attempted to engineer a peaceful mechanism for the selection of the legitimate Ya-Na.

In 1948, the British introduced the rotational system between the two clans. Hence, following the death of Ya-Na Mahama II, his son, who was the regent, failed to succeed his father. The skin was instead passed to the Abudu family. In accordance with the principle of rotation, the next king should have been from the Andani lineage. However, in 1954, the Abudus installed their own member as the next Ya-Na. In this instance, the institution of kingmakers erred in their selection and this culminated in failure of the rotational policy. This failure suggests that a weakness in the system is its dependence on the willingness of the kingmakers who adhere to it.

Subsequently, in 1960, the Nkrumah government also attempted to design an agreeable succession procedure to be adopted in the event of the death of the Ya-Na. In the agreement, it was negotiated that an Andani Ya-Na would succeed the reigning Abudu Ya-Na in 1967. However, an Abudu member was installed as the Ya-Na. The National Liberation Council that overthrew the Nkrumah regime constituted the Mate Kole Committee which annulled the selection procedure for the Ya-Na which had earlier been decided on by the Nkrumah government. Thus the incumbent Ya-Na at that time was declared illegitimate and was forcibly removed from the Gbewaa Palace. A new Ya-Na was then installed in his place.

In the chain of successive government efforts to resolve the issue by deciding on an appropriate way to select the Ya-Na, in 1972 the Acheampong regime tasked the Ollenu Commission to identify the right custom and customary practices of nomination, selection and enskinment of the Ya-Na. In a report similar to a previous investigation, the Ollenu Commission identified the flawed selection procedure that undermined the succession process and subsequently concluded that this controversial process resulted in the illegitimate enskinment of the Abudu Ya-Na. Therefore, the Commission requested the removal of the Ya-Na and the installation of an Andani Ya-Na by using the appropriate processes for selecting the king.

Events reached a cataclysmic point in 2002, when three days of ferocious attacks by both groups resulted in the murder of the Ya-Na and 30 of his supporters in his palace (Tonah 2012; the Wuaku Commission 2002). In response, the Kufuor administration constituted the Wuaku Commission to investigate the matter. The Commission identified the gaps in the management of past events in the disputes, including the selection and succession procedure of the Dagbon state.

In November 2018, the presentation of the Road Map for Peace by the Committee of Eminent Chiefs chaired by the Asantehene was not without the usual controversy associated with this issue. The Regent of Dagbon accused the Committee of divorcing itself from the customs and traditions of the Dagomba people. He contended that the bias of the Otumfuo against the non-partisan kingmakers of Dagbon was palpable. The Eminent Chiefs ignored him to set up this Council to perform their functions. Many of the members of the Committee were princes aspiring to chieftaincy promotions – and even to the Yendi skins. Their mandate included, among others, the offering of advice on the performance of funerals, including that of the Ya-Na, and the appointment of Regent Chiefs to replace those deceased.

The selection procedure of the kingmakers to determine who succeeds the kings has been fraught with confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the Abudus, Andani, and external parties such as the government. Although it has been an arduous and tortuous process, funerals have been performed, and a new Ya Na, Abubakar Mahama Andani, was eventually enskinned on 25 January 2019. Given this highly problematic process, this article recommends a modern electoral college system that will relieve the Dagbon state of the difficulties that have engulfed it for so long.

4. Methodology

The study adopted a qualitative method of inquiry in which in-depth, face-to-face and focus-group interviews with oral historians of the Dagbon kingdom were conducted as sources of primary data. Secondary data in the form of a literature review were obtained from an academic literature review as well as customary documents related to the Dagbon chieftaincy. The study was conducted over nine months in the Dagbon traditional area, in towns such as Yendi, Kuga, Gushegu, Zabzugu, Savelugu, Diare, Tolon, Gukpegu, Kpatia and Tamale. These townships constitute the important building blocks of the Dagbon kinship. The study further collected data from Bimbilla, the traditional home of the Nanumbas, as well as Nalerigu, the traditional home of Mamprusi. This was a form of ethnic group ‘control’ to enable a comparative assessment of the Nanumbas and Mamprusis who emanate genealogically from one ethnic lineage. In the absence of documented charters or written historical documents, public recitations and ethnographic methods of data collection were used.

5. The History of the Dagbon chieftaincy conflict

Abubulai Yakubu (2005:15) traces the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis to 1954 when Ya-Na Abudulai, an Abudu, was enskinned as the overlord of Dagbon under the supervision of the British Colonial Administration. Following independence, there was a series of agitations in the Andani family, who were sympathetic to the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) government. President Kwame Nkrumah subsequently engineered the deskinment of Ya-Na Abudulai. This compelled the government to set up the Opoku Afari Committee and led to the promulgation of the Declaration of Customary Law (Dagbon State) Legislative Instrument 59 (L.I 59). This proclaimed the Dagbon rotational system of succession as a mechanism to provide an equal opportunity for the legitimate family’s ascension to the skin.

Brobbey (2008) argues that a key criterion for the establishment of the rotational system was traceable historical evidence that each family, gate or house had occupied the stool or skin in accordance with the custom and tradition of the people. He concludes that the rotational system is not a panacea for chieftaincy conflicts in Ghana, because there are many examples where families with accreditation to ascend the throne, do not do so after failing to settle on a suitable nominee to occupy the traditional office.

The chieftaincy crisis deepened further in 1966 following the emergence of the National Liberation Council, a military government sympathetic to the Abudu family. The military coup d’état of 1966 introduced new dynamics into Dagomba State politics. In 1967, the National Liberation Council (NLC) set up the J.B. Siriboe and the Nene Azu Mate Kole Committee to study the chieftaincy dispute and to provide recommendations for future settlement. The Committee recommended the repeal of the Declaration of Customary Law (Dagomba State), Order 1960 (L1 59). On 18 October 1968, the NLC promulgated NLCD 296 which repealed the Customary Law (Dagomba State) Decree 1968, (NLCD 281) and Customary Law (Dagomba State) Order, 1960 (L.I 59).

The Decree abolished the rotational system established by President Nkrumah. During the NLC period, the Yendi Skin witnessed both the enskinment and death of a Ya-Na. At the end of the regime, Ya-Na Mahamadu Abudulai was enskinned as Ya-Na.

The National Redemption Council, on assuming office after the military coup in 1972, engaged Nii Amaa Ollenu to investigate the Dagbon conflict – under the Yendi Skin Affairs Committee of Inquiry. The recommendations of the Committee led to the promulgation of NRCD 299 on 5 November 1974. The Decree declared as invalid the nomination, selection and enskinment of Mahamadu Abudulai as Ya-Na and Paramount Chief of the Dagbon State. The Decree further proffered conviction of a term of imprisonment not exceeding ten years to Mahamadu Abudulai and any person or group of persons who recognise him – to imprisonment for not more than three years. Subsequently, the NRCD 299 recognised Yakubu Andani II as Ya-Na and Paramount Chief of Dagbon.

The nature and the wording of the NRCD 299 was anathema to the customs and traditions of Dagombas in particular, and Ghanaians in general. Inasmuch as the NRC sought to bring peace to the Dagbon State, there were inherent contradictions associated with a post-colonial state. The deskinment of the late Mahamadu Abudulai and the enskinment of Yakubu Andani II and the provision to imprison a sitting and now a former Ya-Na who was uncustomarily removed, did not respect the reverence accorded to members of royal families irrespective of the hierarchy of position they occupied at any given time in the Ghanaian society. The nature of the punishment sought for the Ya-Na ought to be considered malicious and repugnant, and is not a durable peace-seeking strategy.

The establishment of the Ollenu Committee and the further promulgation of the NRCD 299 was part of the grand scheme of the military regime to seek political legitimacy from the people through demonisation of programmes and policies of the previous regime. Oquaye (1980:16) notes: “Acheampong made every effort to discredit the Busia administration in every material way.” This included cancellations of all Busia administration policies, which were described as schemes to discredit the previous administration and as justification for the overthrow that occurred.

On 8 September 1979, the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) repealed the Yendi Skin Affairs (Appeal) Degree 1979, S.M.C.D (238) through the AFRCD 32. The Peoples National Convention, which took over power from the AFRC, did not initiate and implement any mechanism to improve the Dagbon chieftaincy problem. The status quo remained until the inception of the new regime.

The Provisional National Defence Council, through the PNDCL 82, repealed the NRCD 299 and the recommendations of the Ollenu Committee. This paved the way for the Abudulai family and Mahamadu Abudulai to challenge the deskinment in an appeal court in accordance with the Court of Appeal Rules, 1962 (L.I 218). The PNDCL 82 provided further reasons for the aggrieved party or family to proceed to the Supreme Court for final redress.

The Abudulai family and Mahamadu Abudulai appealed to the Court of Appeal in accordance with the law. The Court of Appeal rejected the recommendations and conclusions of the Ollenu Committee, thereby granting relief to the family. However, thereafter, on appeal from the Andani family, the Supreme Court overturned the ruling – subsequently sustaining the Ollenu Committee recommendations and conclusions. The fundamental issue was establishing the legality and appropriateness of the selection committee that nominated Ya-Na Mahamadu Abudulai to the Yendi Skin.

The Supreme Court, in order to contribute to the development of the chieftaincy in the Dagbon Traditional Area and to position future perspectives regarding the successions of the Yendi Skin, ordered that:

… having regard to Dagbon Constitution that deskinment is unknown in Dagbon, all persons who have ever occupied the Nam of Yendi shall without regard to how they ceased to be Ya-Na be regarded as former Ya-Nas. Consequently, their sons do qualify for appointment to the gate skin of Savelugu, Karaga and Mion.

This ruling by implication means that sons of all former Ya-Nas qualify to be future Ya-Nas through the gate skins of Savelugu, Mion and Karaga.

The Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) government respected the decisions and judgments of the judiciary; consequently, the PNDC recognised and supported Ya-Na Yakubu Andani II as the legitimate Paramount Chief of the Dagbon Traditional Area. The government then set up a reconciliatory committee in 1987, chaired by Mr E.G. Tanoh, for the rapprochement of the Andani and Abudulai families, and for the peaceful coexistence and development of Dagbon in the future.

The reconciliation committee managed to bring the two families together to agree on the future of Yendi Skin affairs. The families led by Ya-Na Yakubu signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to implement all the elements in the supreme court judgment. A key component of the judgment and of the MoU was to be implemented and respected by all parties. This was the treatment of Mahamadu Abudulai as a former Ya-Na in the event of death, especially burial and funeral rite celebrations. On 16 October 1988, Ya-Na Abudulai died. The family informed Ya-Na Yakubu but he failed to respect the MoU signed by him.

Exercising the state power of coercion and overcoming several attempts at resistance, the PNDC government compelled the Ya-Na Yakubu to allow the Abudulai family to bury the late Mahamadu – after the third day and against Islamic custom and tradition. The Ghana Armed Forces and Ghana Police Service supervised the burial with the instituted dusk-to-dawn curfew in Yendi. The Abudulai family were not allowed by the Ya-Na Andani to perform the final funeral rites after the burial. The Asantehene and the Head of State, Flt Lt J.J. Rawlings made a series of appeals, but the Ya-Na refused the Abdulai family the opportunity. They consequently nurtured and harboured animosity to the Ya-Na Yakubu and waited for an opportunity to perform the funeral rites of Mahamadu Abudulai.

The response to the death of Ya-Na Mahamadu Yakubu by the Andani family infringed the fundamental religious rights of the dead in accordance with Islamic belief. According to Islamic tradition and the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed, as documented in the Quran and the Hadith under the theme “Hasten the funeral rites”, Muslims are instructed, “once death is evident, the body should be prepared and taken out of the house for prayer and burial as soon as possible, in this way, contact with the dead body is minimized, which keeps the grief and hurt of seeing the dead down to a minimum.”1“Hasten the funeral rites” [Collected in all six major books of hadîth. See: Sahîh Al-al- Bukhârî vol. 2, p. 225, #401; Sahîh Muslim, vol. 2, p. 448, #2059; Sunan Abû Dâwûd, vol. 2, pp. 897–898, #3153; Sunan Ibn-i-Mâjah, vol. 2, p. 383, #1477; Mishkat Al-Masabih, vol. 1, p. 338], cited from <http://www.masjidultaqwasandiego.org/resources/quran_hadith_ janazah.pdf> [Accessed 1 March 2014]. Following the 2000 general elections, the country experienced the transfer of political power on 7 January 2001 from the National Democratic Congress, an offshoot of the PNDC, to the New Patriotic Party (NPP), also an offshoot of the Progress Party. The NPP had great support from the Abudu family. From the Abudu side, the NPP government appointed as National Security Coordinator responsible for all security affairs in the country, Major-General Joshua Hamidu; and as Minister for Interior, responsible for all security agencies except the military, Hon. Yakubu Malik; as the Northern Regional Minister, the chairman of the Northern Regional Security Council, Prince Imoro Andani; and as the District Chief Executive of Yendi, the chairman of the District Security Council, Alhaji Habib Tijini. These top security offices strongly advantaged the Abudus in terms of avenging and reversing past injustices inflicted by previous governments and by the Andani family.

In March 2002, the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis emerged once again. The Abudu family began celebrating parallel traditional festivals such as the Bugum, which entrenched their power base and emasculated the authority of the incumbent Ya-Na. The state of affairs grew and festered, causing several clashes between the Abudu and Andani families. This culminated in the murder of Ya-Na Yakubu Andani II and 30 of his supporters in Yendi. The death of the Ya-Na was acknowledged as a new phase in politics in Dagbon, because it led to the opportunity to perform the funeral of the Mahamadu Abudulai, which had been denied by the Ya-Na for 13 years.

The government subsequently established the Wuaku Commission of Inquiry to establish causes of the clashes, to identify the victims, perpetrators and stakeholders, and to make recommendations to deal with the protracted crisis. The Commission identified several security lapses which triggered the violence. Individuals were also recommended for prosecution. The Commission, however, could not reconcile the two families or find any long-lasting solution to the crisis.

Following the recommendation of the Wuako Commission, the government further instituted the Committee of Eminent Chiefs (CEC) to mediate the conflict by establishing an appropriate traditional process for finding a permanent solution to the crisis. It would be a solution which the two families would recognise, appreciate and accept as the final roadmap for peace in Dagbon. The establishment of the CEC corroborates Owusu-Mensah’s (2014) conception of the duality of the political system of Ghana, where a traditional system is contextualised within modern democratic governance structures.

In 2018, the CEC, chaired by the Asantehene, presented to the AkufoAddo government the road map for peace in Dagbon. However, even before the recommendations in the report were executed, there had been opposition to the activities of the Committee, particularly from the incumbent regent. The Regent of Dagbon, Kampakuya-Naa Andani Yakubu Abdulai, raised a litany of concerns about the mediation process to bring peace to Dagbon. The Regent shared his observations that the customs and traditions of Dagbon had been ignored by the CEC tasked with mediating the March 2002 political crisis.

The Regent accused the Otumfuo Committee of bias against the actual kingmakers of Dagbon, because according to him, their roles in the kingdom had been usurped by an advisory council of elders. He contended that the kingmakers initially expressed reservations about the creation of the advisory council of elders that undermined the customs and old traditional institutions of Dagbon. According to the Regent, the Committee’s recommendations appear to be in sharp contrast to the well-established customs and traditions of Dagbon.

The Regent further contended that the CEC had no rights to determine the installation of a Regent for Dagbon and should not have exercised/ assumed such a right. The Regent posited that it was an insult to Dagbon and the State of Ghana that the eminent chiefs had usurped a prerogative over Dagbon that even the government, which appointed them, cannot claim or arrogate to itself under the Constitution.

6. Discussions on Dagbon kingmakers

In a modern state, citizens are enfranchised to directly or indirectly elect leaders for their country for a defined period through constitutionally prescribed processes. Citizens vote directly for a president in presidential systems, while in parliamentary systems the party with the majority of seats in the legislature elects the prime minister to form the government. Conversely, in the traditional political system, the customs and the traditions of the people determine succession of leadership through the institution of kingmakers whose responsibilities and decisions are accepted by the people (and kith and kin) of the traditional area.

The scholarship on kingmakers provides a variety of views. Issifu (2015:28) contends that the Chieftaincy Act of 2008 in Ghana outlines procedures and guidelines for kingmakers on the installation, enskinment, destoolment and deskinment of chiefs. According to the Act, kingmakers must act according to what the law requires. Afolabi (2016:368) describes kingmakers as a group of elders who are consulted on the selection and enstooling or enskinment of chiefs or kings in accordance with the traditions of the people. Beyond the consultation role of kingmakers, Bukari (2016:9) also qualifies kingmakers as people whose backgrounds are deeply rooted in the traditional area, with inheritance of powers to select and install chiefs from their lineage. Omagu (2013:2) and Anamzoya and Tonah (2012:88) stress the relevance of kingmakers in the context of modern democracy. For these scholars, kingmakers are an integral part of the traditional political system. Their role in the selection and installation of chiefs cannot be compromised by any current political dispensation, in spite of advances made by the modern state and the growth of democracy.

As a result of infiltrations into traditional political and cultural systems, corruption and the degeneration of age-old values, the institution of kingmakers has been compromised. Afolabi (2016:10) argues that in some traditional areas the role of kingmakers has been assigned to different groups and stakeholders and kingmakers have been denied the duties to appoint, discipline or remove chiefs. Conversely, Olasupo (2009:335) – using the case of Lagos, Nigeria – notes that the failure of some kingmakers to trace the proper lineage of kingship culminates in unwarranted chieftaincy conflicts. In this case, male kingmakers compromised the ingrained custodian tenets of selection and installation of a new Oba by usurping the powers of women kingmakers – leading to open confrontations between the male and female institutions.

According to Ahorsu (2014:101), kingmakers in the past often came to a consensus on enstooling or enskinning a chief, or on destooling or deskinning a chief, when the said chief had lost legitimacy or had committed an abominable act. These acts of consensus were understood to be protecting the institution of chieftaincy. Ahorsu considers, however, that with the passage of time, it has become increasingly difficult for these kingmakers to live up to their tasks because of the activities of the then colonial administration and nationalist politics.

Nonetheless, Anamzoya and Tonah (2012:88), using the case of Nanumba, consider that kingmakers have done little to promote this age-old institution. They contend that the kingmakers of Nanum have ripped the institution apart by enskinning two different chiefs, leading to serious confrontations among the followers of both parties. They state that this unfortunate event occurred because of a split among the kingmakers. According to them, nine kingmakers of Nanum were expected to settle on one individual to be enskinned as chief, but a legitimate consensus was not achieved.

They assert that six of the kingmakers settled on a son of a former king of Nanum, Mr Andani Dasana Abdulai, as the next king, while the other three kingmakers selected Alhaji Salifu Dawuni, the sitting Nakpa Naa, as successor to the deceased king. The respective kingmakers went ahead to enskin their favourites as chief after they performed the required rituals for him. Anamzoya and Tonah (2012:96) note that kingmakers have a duty to choose carefully in order to protect the institution of chieftaincy. They further argue that the institution of chieftaincy has been destroyed by some kingmakers, who have in fact ignited chieftaincy conflicts.

In this regard, Bukari (2016:11) found that one of the causes of chieftaincy conflicts and disputes in northern Ghana is kingmakers who try to manipulate the selection and installation processes of chiefs. He also identified other factors as the causes of chieftaincy conflicts in Ghana, such as easy access to arms, failure to resolve chieftaincy conflicts using customary indigenous mechanisms and politicisation of the chieftaincy. According to the Ghana News Agency (2017), decisions taken by kingmakers throughout the country have resulted in the loss of lives and property. The consequences of their decisions are important for development, and therefore kingmakers should desist from seeking out their parochial interests and should ensure fairness in their selection of a new chief.

It is evident from the literature that kingmakers have done little to promote the institution of chieftaincy, but are rather destroying an ageold institution which was once held in high esteem and revered by all. The onus lies on these individuals to reinstate the respect the institution commands while learning from kingmakers in the Asante kingdom (Bukari 2016:6).

6.1 The role of kingmakers in the institution of the chieftaincy

Various scholars and studies have highlighted the role of kingmakers in the institution of chieftaincy. For instance, Omoregie (2015:149) states that kingmakers have a vested right in the chieftaincy stool aside from selecting a chief. Bukari (2016:10–14) notes that since the kingmakers aid in the selection and installation of chiefs, they have the responsibility to investigate the background of each candidate to assess suitability beyond eligibility. Using the Bulsa ethnic group in northern Ghana as a case study, kingmakers vote for chiefs at every level including sub-chiefs, divisional and paramount chiefs, by lining up behind the prospective candidates while they vote, after which the one with the highest vote is declared and initiated into the institution of chieftaincy through the appropriate enskinment.

For Anamzoya and Tonah (2012:88-89), in some ethnic groups in Ghana, especially among the Mole-Dagbani, the role of kingmakers in the selection of the appropriate candidate to be the chief of a traditional area is accomplished in phases. Among the Nanumbas, for example, the paramount chief (as one of the kingmakers) selects a candidate for the position of the Bimbilla Naa, and sends colanut through that individual to the other kingmakers to validate his candidature. The acceptance of the candidate by other kingmakers paves the way for progression into the second phase by other kingmakers, including initiation and the main ritual, enskinment.

According to Omagu (2013:2), the selection of chiefs by kingmakers has always been guided by trying to find traits such as honesty, integrity and tolerance in the person selected as chief, coupled with the wisdom of the kingmakers. Olasupo (2009:335) argues that kingmakers are entrusted with the custom and tradition in respect of the selection and installation of a chief, the power vested in the kingmakers enables them to disqualify and exclude persons they consider to be unworthy of the throne – as demonstrated by the expunged selection of the new Oda of Lagos.

Ige (2012:143) discusses the time kingmakers take to execution their function. For example, kingmakers entrusted with the responsibility to select the Oba of Lagos meet within 14 days of receiving the names of the proposed candidates nominated for consideration, and then deliberate on the eligibility and suitability criteria based on the custom and tradition of the people. For Ahorsu (2014:101), kingmakers’ responsibilities go beyond the installation of chiefs. Kingmakers must also act when a chief loses his legitimacy. They must determine the appropriate steps to be followed to ascertain the causes and veracity of the issues raised against the chief.

Staniland’s (1975:172-174) seminal work on Dagbon history and tradition entitled, The Lions of Dagbon: political change in Northern Ghana, analysed the chieftaincy succession system and disputes from the nineteenth century until 1974. He asserts that the key dichotomy in Dagbon is between politics and tradition. Politics refers to external interference in the traditional affairs of Dagbon, either from a political party or any external agent that is not historically connected to customary practices of the Dagbon. However, the nature of the interaction of the Kingdom with the emerging State of Ghana contributed to modifying the traditionally established system.

Others, such as Tonah (2012), believe that the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis has been politicised by the two major political parties in Ghana: the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC). The NPP has strong historical ties with the Abudus family. The party draws political capital from the family and sustains the relationship by rewarding the family with well-paid political positions to demonstrate the partnership. On the other hand, the NDC ties its party-political dividends to the Andani family, particularly in the Northern Region. Similar to the relationship between the NPP and the Abudus, the NDC offers opportunities to the Andani family when in government and seeks to protect the interests of that family. Consequently, Tonah concludes that to resolve the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis, there ought to be concerted determination from both the Andani and the Abudu, the NPP and the NDC, the national government, the Dagbon political and the educated elite. All of these interests must come together to promote a durable solution.

MacGaffey (2006:79–98) believes that the ongoing dynastic conflict in Dagbon which eventually led to the gruesome murder of the overlord Ya-Na Andani, is a reminder of the possibly insuperable conflict in the Dagbon Kingdom that has plagued all successive post-independence governments. MacGaffey (2006) highlights the entrenched positions and other social dynamics and analyses issues of the Andanis and Abudus. These perspectives are expressed through radio stations and religious gatherings. They reflect the inherent contradictions associated with a post-colonial state. They also have developed from the fierce competition from the two families for material resources and reflect their pride in their traditions and beliefs, including associated occult powers in the chiefdom. Indeed, some of these powers are thought to account for the present beneficiary in this family dispute. These beneficiaries are the political entrepreneurs who project and analyse every dispute within the context of chieftaincy conflict between Andanis and Abudus.

7. The customary composition of kingmakers in Dagbon

The Dagomba are a patrilineal people with a patrilocal form of residence. A kingmaker is a male who hails from a family or clan that has the mandate by custom and traditions of the Dagbon to be responsible for performance of this role during the selection and enskinment of the Ya-Na or a paramount chief or divisional chief. The family must recognise such as a person with the responsibility and train him to execute such a sacred customary function after appropriate initiations and traditional rites.

The position of kingmakers has evolved through the generations of Dagomba. The duties of selecting the kingmakers were reserved for the Tindamba (the land priests) who in turn were selected through divinity or soothsaying to choose the appropriate person to occupy the position of kingmaker. The selected candidate is presented to the incumbent king for blessings. However, over the years, various paramount chiefs have been selected to perform this sacred function. These are the GusheNaa, Chief of Gushegu; the Gulpke-Naa, Chief of Gukpegu; the KpatiNaa, Chief of Kpatia; the Tugri-Nam, an elder of the Kuga-Naa; Gomli, a prominent chief for installing the Ya-Na,; the Chong-Naa, the Chief of Chong; the Galigu-Lana, prominent Dagomba Chief in installing the Ya-Na; and the Kalibil-Lana, soothsayer of the Dagomba Kingdom of Gushegu and Gagbindana. According to Dagbon oral historians (for example, drummers and regalia storekeepers), the processes of selecting these kingmakers varies from community to community, and is based on the customs of each community. Whereas the Kpati-Naa’s selection is based purely on divinity through soothsaying, the Gushe-Naa is selected through descent. The role of kingmakers includes three phases. The first step entails the selection of a candidate for king. After this stage, the candidate is grounded in the palace, where he is trained and schooled in the traditions, customs and ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ of a sovereign.

After this period there is the coronation, where the candidate is finally installed as the paramount overlord of the Dagbon Kingdom. This elaborate process is presided over by the Gushe-Naa. The Gushe-Naa selects the appropriate candidate and then other kingmakers commence the investiture of the new Ya-Na. The selection of the prospective candidate and his investiture follows after the funeral celebration of the late king.

Furthermore, Staniland (1975:22) reports that the composition of the kingmakers has persisted through changes attempted by historical negotiations. In 1948, the Dagbon State Council made a resolution to expand the selection body to an 11-member committee of seven divisional chiefs and four elders. These were the Divisional chiefs: the Gushe-Naa, the Yelizoli Lana, the Nantong-Naa, the Gulpke-Naa, the Sunsong-Naa, the Tolon-Lana and the Kumbung-Naa. The Elders were the Kuga Naa, the Zohe-Naa, the Tugri-Nam and the Gagbin-lana. However, the legality of the expanded composition was quashed by the Yendi Skin Affairs Act of 1974 (NRC) Decree 299, which reverted the membership to four.

8. The current situation and continuing frustration with the Dagbon chieftaincy crisis

As stated above, the work of the Committee of Eminent Chiefs (CEC) was stalled in 2009 and resumed in 2018. The Dagbon Traditional Council, members of the two royal families, other stakeholders and members of the public were perplexed about the prognosis of the Ya-Na skin. The fundamental question which the mediation committee aims to satisfy in relation to the appeasement and rapprochement of the two families was: what is the appropriate procedure to elect and enskin the next Ya-Na? The election of any of the two families could trigger another altercation in the traditional area. After a lacuna of ten years, the CEC and the key stakeholders were frustrated with the conflict and sought to settle the problem. A model which seeks to choose an impartial middle-ground of a compromised Zone of Agreement in the pursuit of peace in the Dagbon Traditional Area was therefore developed for this conflict situation.

In 2018, after several attempts by the mediating troika to negotiate with the two feuding families, a report that promised peace in the area was presented to the government. The report paves the way for the proper funeral rites of the late Ya-Nas and the enskinment of the legitimate and substantive Ya-Na Abubakar Mahama Andani. The report has already generated criticism and opposition, especially from the Andani camp. For instance, the Regent of Dagbon notified the president about some concerns where he stressed that the customs and traditions of the Dagomba people were ignored by the CEC tasked with mediating the political crisis which broke out in March 2002. The Regent further highlighted the exclusion of the institution of kingmakers by the committee. He contended that the Advisory Council of Elders created by the CEC is parallel to the kingmaker institution and thus usurps the authority of the kingmakers.

Others, such as Sowatey (2018), further question the role of the Advisory Council of Elders and their expected responsibility in electing the next Ya-Na. He asks whether their duties will be free from influence, bias and interest. Sowatey (2018) highlights the need for the whole process to be receptive to multiple and conflicting interpretations and postulates that the lack of such a receptive environment is a recipe for further conflict. Hence, the last road map, even before it is enacted, is already doomed (in some quarters) and will fail to find an amicable solution for selecting the next Ya-Na – who will be acceptable to all.

9. The electoral college: A solution which can break the deadlock

The Dagbon crisis, albeit intractable, could still be resolved as a state-brokered intervention, but by adopting the modern electoral college system, grounded on the ‘Clean-Sheet Redesign Model’. It could break the family-wrangling deadlocks, paving the way for a rotational succession system to continue.

The electoral college is one of the contested electoral arrangements in political science literature. The contention dates back to the writings of the federalist paper by James Madison. In order to integrate various shades, opinions and perspectives, Wesep (2014:90) proposes an Ideal Electoral College (IEC) system that induces small shareholders to vote in a corporate electoral process to ensure that aggregations of smaller votes have a significant impact on the outcome of the group. The electoral college system exists where a group of people (electors) are elected or selected by the population and who also vote on behalf of the entire population in the selection of the president. This system is commonly used in the United States to elect the president and the process involves the selection of electors, who then meet to elect the president. The objective of the IEC is to create an avenue for fair representation by thwarting the majority votes in a corporate environment of diverse groups who decide on every good and harmful decision. Wesep further contends that votes from the IEC are fashioned on the American model, where votes are classified into two.

10. A Derived Mediation-Intervention Model for resolving the Dagbon conflict

Assumptions:

- The Dagbon Traditional Area has a well-established traditional form of succession, evidenced by accredited kingmakers, whose decisions must be respected by all.

- A Traditional Council exists in the Dagbon Traditional Area.

- This crisis has been bloody with a high potential for recurrence of violence – with national and even regional security implications.

- It is a peculiar type of a family conflict.

- Contemporary social dynamics of the Dagbon society have worsened.

- The conflict can only be resolved at the family level and by the families themselves, guided by the mediators.

- The feuding factions themselves must reach consensus.

- The state reserves the obligatory right under the Constitution of the Republic to restore peace and to ensure progress and development.

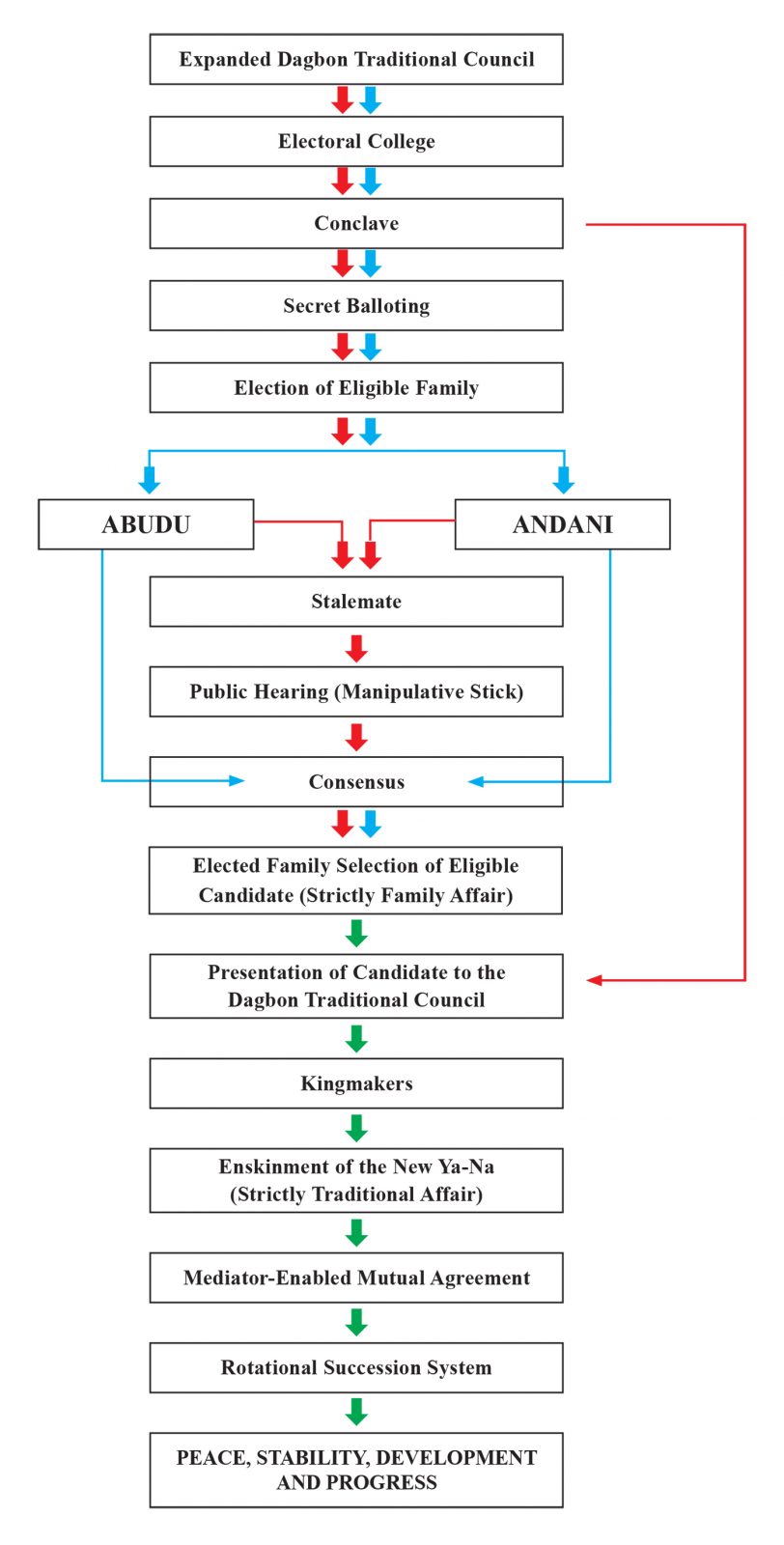

Figure 1: Mediator-Enabled Technical Framework for the Election of the Next Ya-Na

The first stage in the model is to expand the Dagbon Traditional Council to form a model electoral college for the purposes of electing the next Ya-Na. Scholars such as Edwards (2004:90) stress that the electoral college does not emerge from a coherent design based on clearly defined political principles, but exists as a result of complex compromises by stakeholders in search of a consensus. The expanded membership is to include well-meaning traditional leaders and key stakeholders who have a stake and a significant influence in the development of the Dagbon Traditional Area, but are excluded from the traditional council programmes and activities as result of enforcement of rigid traditional and customary membership. These individuals must represent the Abudus and the Andanis families on equal numerical terms: the number must be the same for each family in order to avoid a pre-empted ballot outcome. The expanded traditional council should constitute an electoral college to elect the next family who will select the next Ya-Na.

The electoral college must cast their vote through a secret ballot at a conclave. After lobbying from the two families, the balloting would continue until a family is selected. The electoral college must maintain the principle of equal votes for all the electors. Second, the decision of the electoral college becomes conclusive and binding on all electors. Third, every elector has equal rights, privileges and responsibilities to contribute to the success of the objectives of the electoral college. These principles are central to Robert Dahl’s (2000:37) argument of political equality in the democratic process. He notes that “every member must have an equal and effective opportunity to vote and all votes must be counted as equal”. The objective of political equality is ensuring fair distribution of power between the two feuding families and serves as a signal to the wider family constituencies that the principle of equality has been followed in the political bargaining process.

The proponents of the electoral college argue that it protects minority interests in the political system by offering the opportunity for the integration of perspectives through the allocation of electoral units, which will have been lost without this system. In the Dagbon family gate system, where each of the families battles for recognition from aligned political parties in the country, and where gerrymandering/the splitting up of families is common as a political strategy, the electoral college is a bulwark against the constant wrangling among the chieftaincies.

Conversely, direct election of presidents undermines the federal quota system provided for the states of different sizes.

The electoral college largely promotes and maintains national harmony and cohesion by providing the opportunity for various segments to share the same agenda. It limits the fraud, recounts, corruption and secret dealings of a splintered and polarised system. In the present wrangling about the Dagbon chieftaincy, Abudus and Andanis family members who shield themselves by standing apart as exceptional entities, will be united because they understand the challenging realities of this crisis. They will then advocate for the appropriate family to lead the tradition. The convergence of the two families sharing and voting on an issue, with the possibility of selecting one family, sends an important signal to the entire Dagbon Traditional Area and the country. There is a renewed unity of purpose for the two families.

However, in the event of failure of the conclave, the statutory authority through the mediator should employ a public hearing mechanism as a form of manipulative stick to compel the electoral college to reach consensus.

The composition and processes of a decision-making body are as important as the outcome of the decisions. Globally, the desirability of decision-making models (simple majority or supermajority) is highly contested. These differences have largely found expression in the electoral systems practised in countries across the globe, with some opting for a simple majority model, and others embracing proportional representation and supermajority models. Regardless of the type of model selected, there are pressing issues which make it imperative to give serious consideration to the application of the chosen model. Kwiek (2014) adopted the term ‘conclave’ to describe a decision-making body faced with the challenge of choosing between two alternatives, with each option having the potential to replace the status quo. Reminiscent of the Papal conclave in the Catholic Church, this committee is comprised of prominent individuals who are well versed in the issues under deliberation and understand the dynamics of the game. A key feature of this phenomenon is the high level of secrecy that underlies the processes. In this regard, Kwiek (2014:259) asserts that decision-makers are locked up in a room for the duration of the process and are only released after a decision has been made.

Furthermore, Baumgartner (2003) notes that members of such committees are familiar with the voting rules, despite the high level of secrecy that surrounds their activities. It is, however, imperative that these rules be transparent and fair, to provide a level playing field for voters or parties involved in the process. Members of a conclave largely represent the interests of the electorate and/or institutions and therefore come to the decision-making forum with an obligation to choose an alternative that will best serve the interests of the agencies or people they represent. Even though delays or deadlocks may cause some uneasiness among members of the committee due to the prolonged decision-making, the major concern is about the quality of the decision and what they stand to gain afterwards (Kwiek 2014:259) – and not the length of time they are caught up in in such deliberations. In a context where a simple majority is required, the role of the median voter becomes crucial as they wield the power to make the final decision. On the other hand, extreme voters become vital in cases that require a supermajority (Kwiek 2014:259). Such instances make room for a wide range of competing interests and therefore require more work if a decision is to be reached in the first round of voting. The difference has to do with the fact that whereas a simple majority offers all participants the same votes irrespective of their preferences (indifferent or extreme), a supermajority gives “ultimate power to voters who are not indifferent” and this is likely to enhance efficiency (Kwiek 2014:270).

The state must be involved as a statutory body, because the traditional jurisdiction operates in the modern state as a sub-set of the integrated whole, constituting a social entity whose activity must be regulated and controlled for the common good. The popularly elected statutory representative of the state is at the apex of the social structure as the management agent.

Beyond the election of the family, the elected family progresses to select the next candidate from within their gate in accordance with the laid down statutory and Dagbon customary laws and usage. The candidate is subsequently presented to the Dagbon Traditional Council and enskinned as the next Ya-Na, strictly in according with Dagbon custom and tradition. The mediation committee and other statutory bodies and institutions should be invited to witness the signing and acceptance of the rotational system, whereby the family, which lost the election at the conclave, automatically has the opportunity and privilege to select the next Ya-Na from the appropriate gate. An appropriate implementation of this model could end the family wrangling and create the opportunity for re-institution of the rotational secession system in Dagbon in order to further peace in the Traditional Area.

Conclusion

This article assessed the status and work of kingmakers in Dagbon in the context of tradition and customs of the people, as well as a mechanism for resolving the current impasse in the Dagbon conflict. An ex-post analysis of the Government of Ghana-brokered CEC mediation-

intervention effort, in the wake of an incidental 2002 eruption of bloody altercation, revealed that it was evidently fraught with administrative shortfalls and poor mediator-intervention strategies – in spite of the successes recorded. These poor mediator interventions have been delayed for ten years, to the bewilderment of the feuding families, the Dagomba public, the general public, as well as the government which initiated the process. Consequently, the feuding families should, with the support of the state and its institutional structures, adopt a Clean Sheet model to resolve such chieftaincy problems.

In Dagbon, the institution of the kingmakers and its associated complexities have adversely affected the peace process. So far, all political efforts by successive administrations, including colonial and post-independence governments and traditional means through prominent kings in Ghana, failed to end the conflict. Scholars such as Abdul-Hamid (2011) argue for the abandonment of the obsolete system of selecting the Dagbon king which has been embroiled in controversy, since both sides, at some point, became uncomfortable with its setup and composition. Abdul-Hamid (2011) further advocates an alternative system of selecting the Ya-Nas – but one that is not entirely divorced from the customs and traditions of the Dagomba people. Therefore, for instance, as a religious scholar he highlights the key feature of Islam in the Dagomba way of life and boldly identifies Islam as the surest way to resolve the impasse.

However, as part of the scholarship of politics and seeking a political resolution, this article lobbies for the introduction of an electoral college system to select and install the Ya-Nas. This process will adequately and equally represent all parties from both families. Moreover, it will also include all other stakeholders of the Dagbon state. Even though this system may present some challenges, the key feature of equitable representation and neutrality will ease the pressure. The procedure of selecting a king can be accomplished with transparency, equity and participation.

Sources

Abbott, David W. and James P. Levine 1991. Wrong winner: The coming debacle in the electoral colleges. New York, NY, Praeger.

Abdul-Hamid, Mustapha. 2011. Islam, politics and development: Negotiating the future of Dagbon. Journal of African Culture and Civilization, 4, pp. 47–62. Available from: <https:/www.researchgate.net/publication/308931958>

Ackerman, Bruce 2005. The failure of the founding fathers: Jefferson, Marshall, and the rise of presidential democracy. Cambridge MA: Belknap/Harvard University Press.

Bennet, Robert W. 2006. Taming the electoral college. Stanford, CA, Stanford Law and Politics. 95–121.

Best, Judith 2002. Weighing the alternatives: Reform or deform. In: Jacobson, A. and M. Rosenfeld. eds. The longest night: Polemics and perspectives of Election 2000.

Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 347–360.

Dahl, Robert A. 2000. On democracy. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press. 37.

Declaration of Customary Law (Dagomba State) (Repeal and Revocation) Decree, 1968, State Publishing Corporation, Accra, SPC/A799/3,300/10/68. Diamond, Larry and Leonardo Morlino 2004. The quality of democracy: An overview. Journal of Democracy, 15(4), pp. 20–31

Diamond, Martin 1977. The electoral college and the American idea of democracy. Washington, DC, American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research.

Edwards, George C. 2004. Why electoral college is bad for America. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

Jackson, Robert H. and Carl G. Roseberg 1984. Popular legitimacy in African multi-ethnic states. Journal of Modern African Studies, 22 (2), pp. 177–189.

Jay, John 1788. Federalist paper no. 64. The power of the Senate, Raynold Pamplets, West Margins Press, 2021.

Longley, Lawrence D. 2002. The electoral college: A fatally flawed institution. In: Jacobson, A. and M. Rosenfeld. eds. The longest night: Polemics and perspectives of Election 2000. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 361–370.

Longley, Lawrence D. and Alan G. Braun 1972. The politics of electoral college reform. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

MacGaffey, Wyatt 2006. Death of a king, death of a kingdom? Social pluralism and succession to high office in Dagbon, northern Ghana. Journal of Modern African Studies, 44 (1), pp. 79–99.

Ojo, Emmanuel O. 2007. Nigeria’s 2007 General election and the succession crisis: Implications for the nascent democracy. Journal of African Elections, 6 (2), pp. 14-32.

Oquaye Mike 1980. Politics in Ghana, 1972-1979. Accra, Tornado Publications.

Prah, Mansah and Yeboah, Alfred 2011. Tuobodom chieftaincy conflict in Ghana: A review and analysis of media reports. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 4(3), pp. 20–33.

Staniland, Martin 1975. The lions of Dagbon: Political change in Northern Ghana. (No. 16). Cambridge [Eng.]; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stoog, Louise 2015. Political conflict and the mechanism behind the concept. Paper presented at the XXIV Nordic Conference on Local Government Research, 26–28 November, Gothenburg.

Tonah, Steve 2012. The politicisation of a chieftaincy conflict: The case of Dagbon, northern Ghana. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 21 (1), pp. 1–20.

Van Wesep, Edward D. 2014. The idealized electoral college voting mechanism and shareholder power. Journal of Financial Economics, 113 (1), pp. 90–108.

Wilmerding, Lucius Jr 1958. The electoral college. New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press.

Wuaku Commission Report 2002. Executive summary of the Wuaku Commission Report.

Available from: <http://dagbon.net/yela/Wuaku%20Commission%20Report.pdf> [Accessed 15 October 2011].

Yendi Skin Affairs Decree, 1974 (NRCD 299), Gazette Notification date: 15 November 1974.

Yendi Skin Affairs (Appeal) Law, 1984 PNDCL 82, Ghana Publishing Corporation, GPC/A 296/4.250/6/84, Accra.