Introduction

Much has been written on the politics of food aid. In the literature,1 food aid has been variously depicted as necessary to address the chronic food insecurities in poor countries; an instrument of foreign policy by donor countries; destroying local agriculture while securing markets for subsidised farmers in donor countries; entrenching the dependency syndrome; and fuelling the rampant practice by politicians of using food aid to reward supporters and punish opponents. A little known, if not more insidious, dimension of the politics of food aid is its impact on communities at the grassroots level.

This article focuses on the Tandi chiefdom in rural Zimbabwe and critically examines the dynamics, impacts and politics of food aid distribution at grassroots level. The article shows that the food aid distribution system is flawed and is abused by villagers, and that village politics determines who gets food. It identifies the inherent flaws and popular criticisms of the food aid distribution system. Specifically, it shows that the selection of food aid recipients is not always based on the “poorest and most vulnerable” principle as espoused by donors, but is oftentimes determined by the village politics of kinship, alliances and power. Consequently, some of the poorest and most vulnerable fail to get food aid, while some of the rich get it. Even worse still, food aid tends to exacerbate community conflict, promote laziness and entrench the dependency syndrome. The article ends by considering policy options to address some of the challenges of the food aid distribution system.

Analytically, the article provides a micro-level analysis of the relationship between village politics and food aid distribution, and of the unintended consequences of free food aid. It exposes the underlying oppressive structures that produce egoistic and violent behaviour exhibited during food aid distribution. Methodologically, it is based on critical observations and interviews conducted by the author during the 2008–2009 food aid distribution in the Tandi chiefdom.

Context

Food insecurity in Zimbabwe dates back to British colonial land dispossession. Robert Mugabe’s attempt to redress these colonial injustices through a chaotic and violent land reform, which started in 2000, worsened the food security situation, and transformed the country from being Africa’s bread basket to a nation dependent on food aid. The 2008–2009 drought compounded an already bad situation, and forced about 3 million people to depend on donor food aid2 and vegetation. Villagers in the Tandi chiefdom were not spared the wrath of the drought.

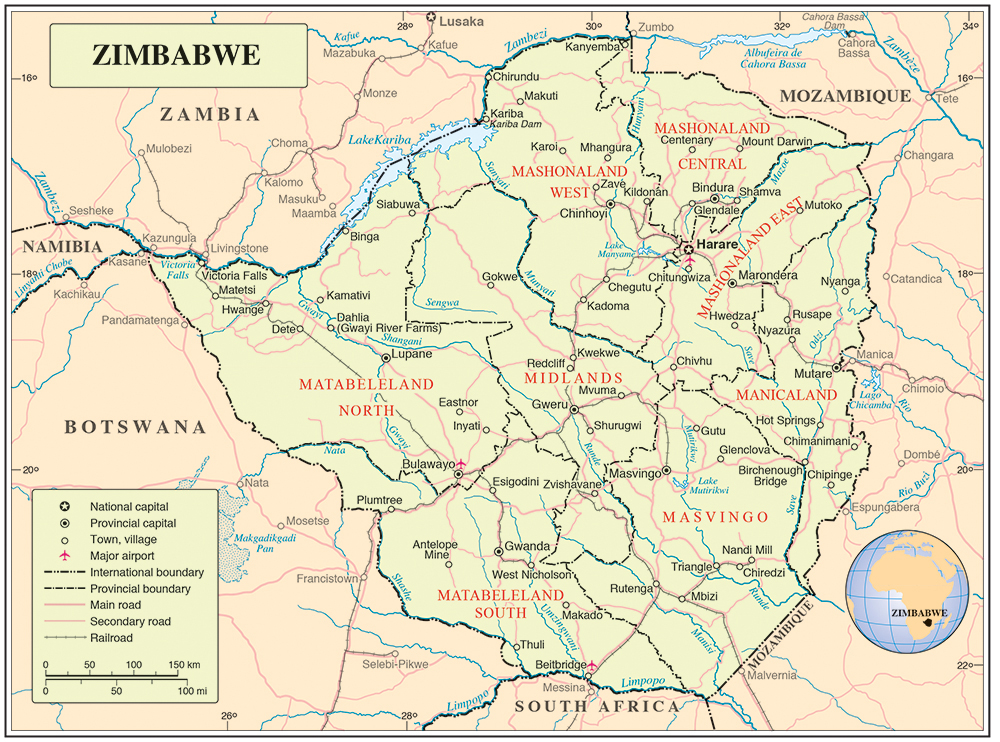

The Tandi chiefdom is in the Makoni District of Manicaland Province and about 170 km south-east of the capital city, Harare. The chiefdom has 46 villages, with households ranging from seven to over 40 per village. As the area is semi-barren and overly populated, villagers grow mainly maize on small pieces of land. Some own small heads of cattle. Not surprisingly, many villagers in the chiefdom survived the 2008–2009 drought through food aid.

Presenting emergency food aid support funds to the World Food Programme (WFP), Dave Fish, head of the United Kingdom’s aid programme to Zimbabwe, said:

The UK has given $6.7 million for food aid that will help reach 1.8 million of the poorest and most vulnerable Zimbabweans in the lean months.3

Feeding the poorest and most vulnerable is indeed a noble deed. However, the experience of the Tandi chiefdom demonstrates that the reality on the ground is a far cry from this noble ideal; accurately targeting the most vulnerable is a complex and difficult task.

Village politics, characterised by backstabbing, corruption and jealousy,4 has compromised the “poorest and most vulnerable” principle of the food aid distribution system. Not infrequently, some of the poorest and most vulnerable fail to access food aid, while some of the relatively rich receive the aid, thereby widening the gap between the rural poor and the rich.

Flaws of the Food Aid Distribution System

In theory, the WFP humanitarian food aid distribution programme is based on the “poorest and most vulnerable” principle. The most vulnerable are defined as poor families with no source of income – usually comprised of orphans, young children, widows, the elderly and the disabled. However, this system is flawed and is open to abuse by villagers, and has many other negative unintended consequences.

First, targeting the poorest and most vulnerable only may not be the most effective strategy for addressing persistent poverty. Among other things, focus on poverty only allows other important issues – of economic injustice and development policy, for instance – to slip out of view. Therefore, to effectively assist the poorest and most vulnerable, vulnerability assessments should be more detailed, holistic and inclusive.

Second, the exclusive focus on the individual and the “numbers game” of counting heads in a poor household is problematic. Not only is accurately ascertaining the level of individual vulnerability difficult and costly, but also by focusing on the individual, the selection criteria ignore family and class background. Thus, individual orphans are considered the most vulnerable, yet it is their family and class background that determines their level of vulnerability and standard of living. Through inheritance as well as assistance from extended family members, orphans from rich families are better cushioned against poverty than children of living poor families: a late “rich dad” can be a much better provider than a living “poor dad”.

Third, allocating food aid to the individual child contributes to the disintegration of the family by undermining the authority of elders. In the past, elders had control of economic resources. Now, with the donor perceived as the new rich godfather, that source of power and authority is being eroded. Some children who receive food aid are becoming rebellious against their pauperised guardians, claiming the right to do whatever they wish with “their” food aid; some end up stealing and selling it.

Fourth, because of the focus on age – namely, young children and the elderly – young adults are excluded from the food aid programme on the fallacious presumption that they are still energetic and productive, and therefore able to fend for themselves. The reality is that owing to the economic crisis of the last decade, most young rural adults have never had formal employment, and indeed are among the poorest and most vulnerable of the rural people. Unlike some of the elderly, who are either supported by their adult children and/or own bride wealth cattle as well as rented houses in towns, young unemployed adults do not own any valuable assets. In one village, for example, the focus on age led to an absurd situation in which elderly but relatively rich villagers – a family that owns the biggest shop at a local business centre, and another that owns a farm, a truck and rental houses in Harare – qualified as beneficiaries, while the poor young adults who do casual work for these families were disqualified.

A fifth shortcoming is the insensitivity to gender, and especially to the plight of young single mothers. In traditional Shona society, women are considered minors, and this means that poor single mothers living with their parents are not eligible for food aid in their own right. Rather, whether or not they receive food aid depends on the eligibility or otherwise of their guardian. In one such case, a poor single mother, her child and two orphan cousins all had to depend on the meagre pension of their great grandfather, who they live with – all pensioners (and workers) are ineligible for food aid. Poor, vulnerable and discriminated against, some of these young women end up as sex workers, thereby exposing themselves to HIV/AIDS and premature death (as happened to the young woman in this case). All this gives further momentum to the vicious circle of poverty.

A sixth challenge relates to village size. There seems to be a threshold number of people in a village that donors are comfortable feeding at a given time. When this number is exceeded, and regardless of the degree of vulnerability, the “excess people” are denied food. In other words, the relatively well-off in smaller villages stand a better chance of receiving food aid than the relatively poorer in bigger villages; in the smallest villages, everyone usually gets food aid.

A seventh challenge: giving bigger families more food, while understandable, encourages the poor to have bigger families – which, in turn, exacerbates the problems of poverty and hunger. For example, when bulgur wheat – considered a delicacy by the poor – was only given to families with six or more children, some of those with smaller families openly wished they also had bigger ones too. When the poor keep over-procreating, the hope of ever breaking the vicious circle of poverty diminishes. Finally, the automatic privileging of disability without assessing the level of disability may “disable” the selection system’s capacity to reach the most vulnerable. Some relatively well-off people with minor disabilities that only marginally affect their productive capacity have been regular food aid recipients. One such recipient – a partially disabled but relatively rich farmer – is able to sell his produce because he receives food aid all the time. The point is: disability is not synonymous with inability, and its extent should therefore be assessed accurately.

Selection of Food Aid Recipients

Beneficiaries are selected through a rudimentary process in which the villagers identify and vote for those eligible. The selection criteria are open to abuse and manipulation by villagers. The process also exposes the limits of village democracy. Chiefs and headmen play a prominent role in identifying beneficiaries in their villages, and food aid disbursement offers them an opportunity to assert their fragile authority. It allows them to punish dissenters by excluding them from the beneficiary list, and reward supporters by including them.

Further, and with even more serious implications, villagers form alliances in vetting and voting for potential beneficiaries. In a manner not too dissimilar from vote buying by corrupt politicians, they vote for one another reciprocally, or in exchange for food and other favours. It is not uncommon for those voted for to give a portion of their food to those who voted for them. In closely knit villages, all the members, including the relatively rich, regularly receive food aid.

Poor, Vulnerable and Unpopular

The poorest and most vulnerable have great difficulty being popularly voted for, for they are too poor to afford resources (such as goods to give to neighbours) for social networking and mobilising support. In addition, poverty comes with low self-esteem, lack of confidence, and a sense of failure and being unentitled. All these factors militate against the capacity of the poorest and most vulnerable to defend their interests vis-a-vis those of the powerful.

There are quite a few categories of the poorest and most vulnerable who, for some reason, are unpopular with other villagers. For example, orphans and the elderly who are forced to stay with relatives in other villages usually fail to get food aid as they are considered outsiders. Typically, they are rejected by villagers of their new homes as “aliens” and by their old villages as “exiles”. New arrivals from other parts of the country are routinely excluded from receiving food aid and dismissed as “strangers”.

Another group that tends to be excluded from receiving food aid is the previously well-off, but presently down and out.

One such family, visibly distraught and malnourished, complained bitterly for being consistently voted out of the food aid programme. A beautiful house, built during the “good old days”, caused jealous neighbours to disqualify them for food aid.

Yet another example of a victim of village politics is that of a prophetess with three vulnerable children of her own and another three orphan wards from her deceased sister. Although they are probably the poorest family in her village, she has never been voted for to receive aid for allegedly exposing the “evil” ways of other villagers. The prophetess has had to abandon her home and relocate to a peri-urban shanty town on the outskirts of Harare. In a nutshell, the dynamics of village politics means that power, networking and alliances determine who ultimately gets food aid.

Abuse of the System

The food aid distribution system is open to abuse by many. In one case, a headman was accused of including on the beneficiary list names of deceased people, and receiving the food himself on their behalf. It is alleged that some of the new arrivals try to beat the system by getting food aid in both their old and new villages. Many more inflate the number of their dependent children, usually including independent children.

Some recipients of food aid sell it, while others use it to pay for casual farm work (or to feed chickens, in the case of bulgur wheat). Quite often, casual farm workers are the poorest and most vulnerable who fail to access food aid. In addition, the process of selecting beneficiaries generates conflict within communities.

Community Conflict

Since everyone wants to get something of the little food aid available, it is not surprising that the Hobbesian5 egoistic instinct of self-preservation looms large in food aid beneficiary selection. With villagers using food aid distribution to settle scores and/or to profit, the outcome is rising conflict. For example, a male villager spent six months in jail as a result of a physical fight with another villager’s wife over his alleged unfairness in portioning out donated rice. In another case, two village women were in a conflict after one of them revealed that the other only had one child and not two dependent children.

In another case, a woman was warned by an angry neighbour whom she had “sold out” that: “We will use the cooking oil you have received at your funeral.” The “traitor” is since deceased. Given the strong superstitious beliefs among villagers, her death was attributed to witchcraft by the one she had “sold out”. In all these examples, relations between the extended family members of the parties to the conflict became strained, and when other villagers were forced to take sides, the village became polarised.

Popular Criticisms

Popular criticism against food aid is mounting. First, donors are criticised for offering what they have and not what recipients need – for instance, rice and cooking oil instead of seeds and fertiliser. Not surprisingly, some recipients end up selling food aid to get money to buy other basic essentials not provided by donors.

Second, food aid is said to make planning and budgeting difficult. As one villager complained:

It is difficult to plan and budget when you don’t know when they (donors) are coming next, and how much they are bringing.

Third, waiting for food aid – oftentimes in vain – is time-consuming and causes anxiety. Often, when rumours spread that food aid is coming, villagers flock to the food distribution point only to be sent back home empty-handed, angry and hungry. Finally, those who fail to receive food aid are scathing in their criticism, and their angry outbursts are quite revealing:

WFP should never come back again; it is promoting laziness; free food will not take us far; it is embarrassing and humiliating to keep being fed by other people; we want to farm and feed ourselves as we have always done, but now in addition to political sanctions, we also have God’s sanctions – drought.

The desire to become self-sufficient seems to run through these popular criticisms. Therefore, policy changes should create conditions for a realisation of these dreams.

The Way Forward

The politics of “who gets what and why” of the food aid – especially when too few of the many who are hungry get it – is potentially destructive and destabilising. New innovative ideas, as suggested below, are needed to deal with this challenge.

A local chief reasoned that since drought affects everyone, everyone should be given a little of what is available. Some felt that instead of providing a complete package – of cooking oil, beans/peas and maize – to a selected few, donors should provide only maize to everyone, as maize meal is the most basic staple. Others suggested that to discourage the pervasive “free dinner” mentality, the food should be sold at affordable prices.

A long-term solution should be holistic. First, it should involve capacitating the poor to become self-reliant and graduate from being “aid recipients to becoming aid providers”, as happened to the beneficiaries of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID’s) Enhancing Nutrition, Stepping Up Resilience and Enterprise (Ensure) project.6 After receiving agricultural resources, participants were able to produce surplus food, which was bought by USAID and given to the vulnerable. Second, empowering the poor should also include training them in better and environmentally sustainable farming techniques, as well as encouraging them to grow drought-resistant crops.

Finally, since the chaotic land reform process contributed substantially to a decline in food production, the subject should be revisited with a view to making farms productive again. A 1998 conference on “The Land Question in Zimbabwe”, held at the University of Cambridge, recommended a win-win outcome in which only the unused part of farms would be reallocated.7 This would have avoided the disruption of production and its catastrophic consequences, the suffering endured by displaced farmers and farm workers, the looting of farm equipment, and the need to compensate farmers. It would also have promoted racial reconciliation and even the learning of new skills by new farmers from the established farmers. Such an approach, which should involve consultations with all stakeholders, seems the only way that stability and development can be achieved.

Conclusion

Colonial land dispossession, chaotic land reform and drought have all conspired to produce food insecurity of catastrophic proportions in rural Zimbabwe. Consequently, humanitarian food aid has become a major source of livelihood sustenance for many of the country’s rural poor. The dynamics of village politics, coupled with the inherent flaws of the beneficiary selection system, mean that some of those who deserve food aid sometimes fail to get it, while the undeserving get it. To address the inadequacies of the food aid distribution system effectively, a holistic policy rethink is essential.

Endnotes

- Riley, Barry (2017) The Political History of American Food Aid: An Uneasy Benevolence. New York: Oxford University Press; and Paarlberg, Robert L. (1982) Food Policy and Farm Programs, Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, 34 (3),

pp. 25–39. - Howe, Doreen (2019) Former Aid Recipients Become Aid Providers. Newsday, 23 April.

- Fish, Dave (2009) UK’s Aid Programme to Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwe Independent, 11–17 December.

- Werbner, Richard (2011) Tears of the Dead: The Social Biography of an African Family (2nd edition). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hobbes, Thomas (1651) Leviathan. Available at: <www.eBook.Library.org> [Accessed 22 April 2019].

- Howe, Doreen, (2019) op. cit.

- The conference was organised and chaired by the author and the then Zimbabwe Ambassador to the United Kingdom, (the late) Ngoni Chideya, was the guest of honour and a key-note speaker. Chingono, Mark (1998) The Land Question in Zimbabwe: Conference Report. University of Cambridge Newsletter, July. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.