Introduction

This article reflects on the review of United Nations (UN) peace operations by the UN High-level Independent Panel, appointed by the UN Secretary-General in October 2014, and on its implications for Africa and the Training for Peace (TfP) in Africa Programme. Africa’s security environment has deteriorated, with difficult security challenges defying solutions. Contemporary conflicts are riddled with evolving hybrid and asymmetric threats that weave a complex pattern of interconnected terror, mayhem and destruction. These threats continue to undermine the human security platform and destabilise African states and their citizens. The UN, African Union (AU) and regional economic communities/regional mechanisms (RECs/RMs) are courageously working to respond to these challenges.

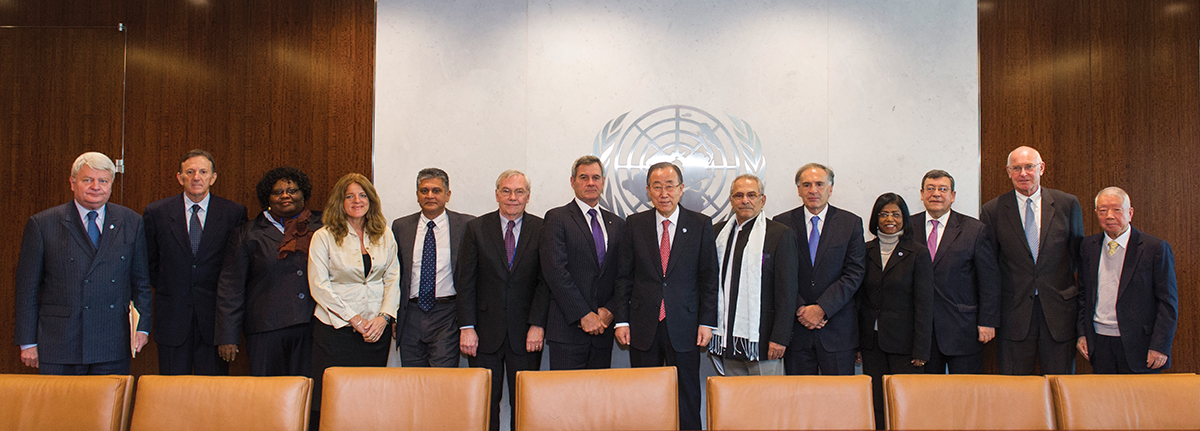

“The world is changing and UN peace operations must change with it if they are to remain an indispensable and effective tool in promoting international peace and security.”1 These words were spoken by the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki Moon, when he announced the establishment of the UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations on 31 October 2014. The UN Panel was tasked with undertaking a comprehensive assessment of the state of UN peace operations to date, and identifying the needs of the future. In its terms of reference, the UN Panel was tasked to cover the changing nature of conflict, evolving mandates, good offices and peacebuilding challenges, managerial and administrative arrangements, planning, partnerships, human rights and the protection of civilians, and the capabilities of the uniformed services for peacekeeping operations.

Peacekeeping Challenges on the African Continent

The African continent has not been immune to new and emerging conflict dynamics. If anything, Africa has been worst hit by these new phenomena compared to other regions. Making comparative reference between the rest of the world and Africa over the past 40 years and commencing with the 1990s genocide in Rwanda; the Burundi crisis; the clan wars of Somalia; the Eritrea–Ethiopia war; the Sudanese civil war; Morocco and the Polisario Front; the Darfur conflict; the civil war in South Sudan; the unending carnage in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); the devastating civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia; the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya; the Comoro Islands, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Central African Republic (CAR) conflicts; the Lesotho electoral dispute and a few more that remain latent, Africa has numerically witnessed more conflicts than any other region of the world.2 African conflicts have been characterised by extreme violence and atrocities committed against innocent and defenceless civilians.

These conflicts have elicited responses from the AU, but interventions have not guaranteed sustainable peace. Most conflicts continue to simmer, and electoral processes bring to the surface the deep-seated, underlying social and political tensions that manifest in identity, ethnic, religious and cultural dimensions. The recent election-related tensions in Lesotho and the current tensions in Burundi preceding the upcoming elections are cases in point. The African continent has been challenged to its full capacity to respond, and this has necessitated a review of the African peace operations capacity and responses to conflicts, and associated guiding mandates. In essence, the traditional tool provided for under Chapter VII of the UN Charter3 has become ineffective in response and has therefore pushed Africa to craft a ‘fit for purpose’ response that is more realistic. The ‘stabilisation approach’ – armed military intervention that seeks peace in a volatile environment – has produced better results, and has thus become the modus operandi and tool of choice for Africa.

As conflicts escalated in Africa, the Heads of State and Government Summit of 2003 decided to establish the African Standby Force (ASF), believing this to be the most appropriate and ideal method to respond, manage and hopefully remove the rising scourge of conflict from the continent. It was decided then that the five main regions in Africa would establish standby formations that would constitute the building blocks of the ASF. The preference for peaceful intervention to conflicts through preventive diplomacy, mediation and negotiation also called for the establishment of mediation mechanisms and capacities in the RECs/RMs. By 2005, four of the five regions had established standby structures that included mediation mechanisms.

The UN peace operations review came at a most opportune moment in the history of conflict management on the African continent. The AU was considering carrying out a similar assessment of its peace operations, following the findings and recommendations of an independent panel of experts in a 2013 assessment of its peace and security structures, when the UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations conducted its assessment.4 It was therefore only logical that the findings of the UN Panel be adopted for further analysis, consideration and use by the AU.

The Transformation of Peace Operations in Africa

A widely recognised lesson is that in the African security landscape, the traditional principles of multidimensional UN peacekeeping missions no longer fit because virtually all African peace operations are deployed in places where there is no peace to keep, due to continued violent conflict. Deploying stabilisation missions characterised by robust peacekeeping to stop the fighting, stabilise the security situation, and protect civilians and the peacekeepers themselves, has thus become the norm. This new realisation justified a review of the operational tactical approach. The changing conflict dynamics inevitably foster reform of the current approaches to peace operations by encouraging innovative and widely consultative considerations and flexible adaptation to new circumstances, adopting best practices and lessons learned from elsewhere and own operations, conducting constant reviews and thoroughly monitoring and evaluating operations.

While the conduct of operations planning is not yet fully systematic, despite significant training on the multidimensional character of contemporary peace operations, the skills acquired in the ASF are beginning to influence understanding within authority structures, for the need, relevance and value of coordinated and integrated planning. The ASF, which has consistently been building peacekeeping capacity over the past two decades, is a structure of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), and this signifies African recognition of the importance of collaboration, cooperation and coordination among the AU, RECs and the UN.

Coordination and Cooperative Partnerships among African Peace Operations Stakeholders

Closer consultation, collaboration, cooperation and coordination among all AU peace operations stakeholders should generate trust, confidence and ownership of peace operations on the continent. The complex relationships between terrorism and criminal networks have reduced the impact of traditional peacekeeping, because such hybrid and asymmetric threats challenge existing peacekeeping capacities, skills and capabilities. However these threats can be diffused with dedicated cooperation.5 Terrorism transcends borders and conflict hotspots are not predictable, hence the greater need for cooperation and coordination among states and regional organisations. This should be enhanced by timely information-sharing among the key role players to enable effective responses to the diverse threats evolving in Africa.6

Robust peace operations capabilities have so far managed to contain aggression and ensure basic stability. This should not be viewed and taken as an end in itself, because political problems require political solutions that ensure the establishment of sustainable solutions. African peace operations capacities have developed considerably with the facilitation of the UN through the UN Office to the AU (UNOAU) mission support, which has enabled the deployment of a significant number of peacekeepers in Africa in recent years. In 2014, the UNOAU Commission’s Peace and Security Department signed a Joint Framework for an Enhanced Partnership in Peace and Security, which is an effective tool that frames, promotes and guides joint work, coordination, cooperation and support in responding to conflict challenges on the continent.7

The AU – the body with the ultimate authority on continental matters – has also recognised the value of partnerships with the RECs/RMS and signed legal instruments that govern relationships within the framework of the APSA. However, there should be a shared need between the AU and RECs/RMs to see improved cooperation and collaboration among the APSA partners. Partnerships are therefore central to the interventions designed in response to conflict challenges. Collaboration among African partners should be pursued relentlessly, and the relevant coordination structures should be established beforehand. The UN Security Council, in Resolution 2167,8 underscored the importance of developing effective partnerships in the area of peacekeeping between the UN and regional organisations.

Significantly, the interaction between the UN and the AU is better now, due to cooperation and consultation among the leadership and officials. The successes of the AU-mandated responses in the Comoros, Mali and CAR signify positive consultations and collaboration within the leadership levels and show progressive improvement of peace operations capacity on the continent. The tensions that characterised the UN, AU and the Economic Community of West Africa (ECOWAS) during the Mali and CAR interventions will not resurface at any time if all the underlying inequalities and asymmetries in power are clarified in good time. However, it would be important for the UN and AU to understand that the RECs, with their in-depth subregional and local knowledge, are important partners and provide a good platform to respond to conflict timely, holistically and effectively.

Peaceful Resolution of Disputes

The AU’s Constitutive Act calls for the peaceful resolution of disputes – but most often dialogue or mediation have not been the first tools of choice by the AU to intervene in the pursuance of peaceful outcomes. The UN and AU have both encouraged the formation of regional mediation structures,9 which should work together with the AU Panel of the Wise10 to intervene and help resolve conflicts peacefully. Most African conflicts revolve around electoral disputes and issues of democratic governance, so there should be scope for peaceful intervention first. Like the UN, the AU equally has the authority and mandate to ensure that member states adhere to the principles of good governance, democracy and human security to minimise potential for conflict.

Mediation is one of the preferred conflict resolution approaches that has been adopted by the AU. The recent launch of the Pan-African Network of the Wise (PanWise)11 complements the efforts of the Panel of the Wise, special envoys and diplomats, and good offices. PanWise aims to promote a much broader mediation approach that ensures the involvement of local, national, civil and regional actors in building sustainable and competent conflict resolution capacities on the continent.

The African conflict landscape is volatile, and professional knowledge and expertise in conflict intervention and management has been marginal. Mostly, African interventions are cushioned in a strong belief in political and military power. As such, the few intervention attempts on the continent have yielded staggering successes. Despite dialogue and mediation being recognised as useful tools for conflict prevention and resolution, not enough time and resources are committed to the development of these skills when compared to the massive investments made in building military capacities. The need for capacity-building training and experience-sharing workshops, aimed at deepening the knowledge and skills of AU mediators and building a pool of high-level mediators on the continent, is critical. Further, appointed mediators, who are often deployed in highly complex environments, should have the considerable support of country and regional analytical, thematic communications and management, and administrative and financial expertise, for them to be effective.

The exclusion of women from mediation activities within the African intervention framework undermines and robs Africa of the value and benefit that women bring into conflict intervention efforts.12 However, the appointment of Bineta Diop as AU Special Envoy for Women, Peace and Security has been a significant indicator that the AU is promoting the visibility and status of women in continental peace and security matters. Another significant contribution by women in issues of high-level diplomacy, under the auspices of the AU, was Graça Machel’s13 intervention in the Kenyan crisis, which served to douse the anger of women by ensuring their involvement in the search for peace. The Report of the Secretary-General on Women, Peace and Security clearly outlines the UN’s efforts to address gender imbalances in mediation, peace and security. The AU and RECs/RMs have also taken a cue from such UN efforts.

Mission Support Capacity

Despite the current weaknesses in AU mission support to its peace operations, the Peace and Security Division (PSOD) works tirelessly to improve resource support to peace operations. The cooperation between the UN and AU through the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and the UN Support Office to AMISOM (UNSOA) has been embraced as a model that will gradually empower and capacitate the ASF in mission support through knowledge transfer. While working hard to build internal capacity to support deployed missions effectively, the AU may still need international assistance for its deployed missions. However, only recently – with the adoption of Agenda 2063 that opens a new chapter in cooperation between the AU and the private sector – is there recognition of the relevance of the private sector to freeing Africa from dependence.

Protection of Civilians

The violent nature of contemporary conflicts has emphasised the need for collective and coordinated responses to confront emerging threats. For effective responses to threats, clear and appropriately worded mandates have become a necessity, to remove the ambiguities often associated with mandates. The protection of civilians contributes to a peaceful mission environment, and protection mandates have been found to reduce human suffering in conflict areas significantly. Recent AU peacekeeping operations mandates have shown substantial change in their wording, which now contains a specific focus on the protection of civilians.

Implications for TfP

The UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations brought to the fore the need for an African debate on the future of African peace support operations. The report of the UN Panel is due to be released in June 2015, and is likely to reveal weaknesses that cut across all the peace and security structures – from the international to the continental, and to the regional and national levels. The TfP Programme was also reviewed in 2014, and it would be useful for these two reviews (UN and TfP) to be read against each other so that complementarities and synergies can be identified. Strategies for the future can then be formulated and appropriate decisions taken.

Various independent evaluations over the 20-year history of the TfP Programme have found that it has made a meaningful contribution to the development of civilian and police capacity in Africa. The evaluations also found that the TfP Programme evolved and adapted as peace operations shifted from traditional peacekeeping to integrated and multidimensional peace support operations, and that TfP has consistently been ahead of the curve. As the AU – and, to some degree, the UN – is now shifting towards stabilisation operations, TfP is already supporting the AU with the development of related stabilisation and protection of civilian courses. The work of the UN Panel and the research of the TfP Programme suggest that some of the most important attributes a programme such as TfP needs to have is the ability to be flexible, adaptive and innovative. This can only happen when such a programme has clear goals and objectives, coupled with a management structure that facilitates responsiveness to changing needs and encourages adaptation.

Endnotes

- The United Nation Secretary General (2015) ‘The Briefing Notes on the High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations’, p. 2 para. 1. Unpublished paper for the UN High-level Independent Panel, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, February 2015.

- Jackson, Richard (2002) ‘Internal Conflict and the African State: Towards a Framework of Analysis’, Available at: <http://cadair.aber.ac.uk/dspace/bitstream/handle/2160/1953/Jackson,+Violent+Internal+Conflict+and+the+African+State.pdf?sequence=1> [Accessed 14 May 2015].

- United Nations (n.d.) ‘Charter of the United Nations’, Chapter vii Article 39, Available at: <http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/intro.shtml> [Accessed 24 May 2015].

- De Coning, Cedric, Linnéa, Gelot and Karlsrud, John (n.d.) Strategic Options for the Future of African Peace Operations (2015–2025). NUPI Report, pp. 8–9.

- Okeke, Jide Martyns (2015) Redefining United Nations (UN) Peacekeeping in Africa: Lessons from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Center on International Cooperation and International Peace Institute, p. 9.

- Tardy, Thierry (2015) Case Study: European Perspective on the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Center on International Cooperation and International Peace Institute, p. 5.

- De Coning, Cedric, Linnéa, Gelot and Karlsrud, John (n.d.) op. cit. , pp. 14–15.

- United Nations Security Council (2014) ‘Resolution 2167 (2014), Adopted by the Security Council at its 7228th meeting, on 28 July 2014’, Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2167.pdf> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- African Union (n.d.) ‘Mediation Relationships between the AU, RECs and Partners: A Report Based on a Seminar Organised by the African Union Commission on 15 and 16 October 2009’, Available at: <http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/3B408148510828464925779F00068B10-AU_Mediation.pdf> [Accessed 14 May 2015].

- The Panel of the Wise is an AU consultative body, made up of five appointed members. It is mandated to provide opinions to the Peace and Security Council on issues relevant to conflict prevention, management and resolution.

- PanWise is a pan-African network, established by the AU, that brings together various mediation actors and mechanisms to strengthen, coordinate and harmonise prevention, early response and peacemaking efforts carried out by various actors in Africa under a single umbrella.

- United Nations (2011) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on Women and Peace and Security’, UN S/2011/598, Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/WPS%20S%202011%20598.pdf> [Accessed 13 May 2015].

- Kofi Annan Foundation (2009) ‘The Kenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation: One Year Later’, Report of the Meeting, Geneva, 30–31 March 2009, Available at: <http://kofiannanfoundation.org/sites/default/files/KA_KenyaReport%20Final.pdf> [Accessed 14 May 2015].