Introduction

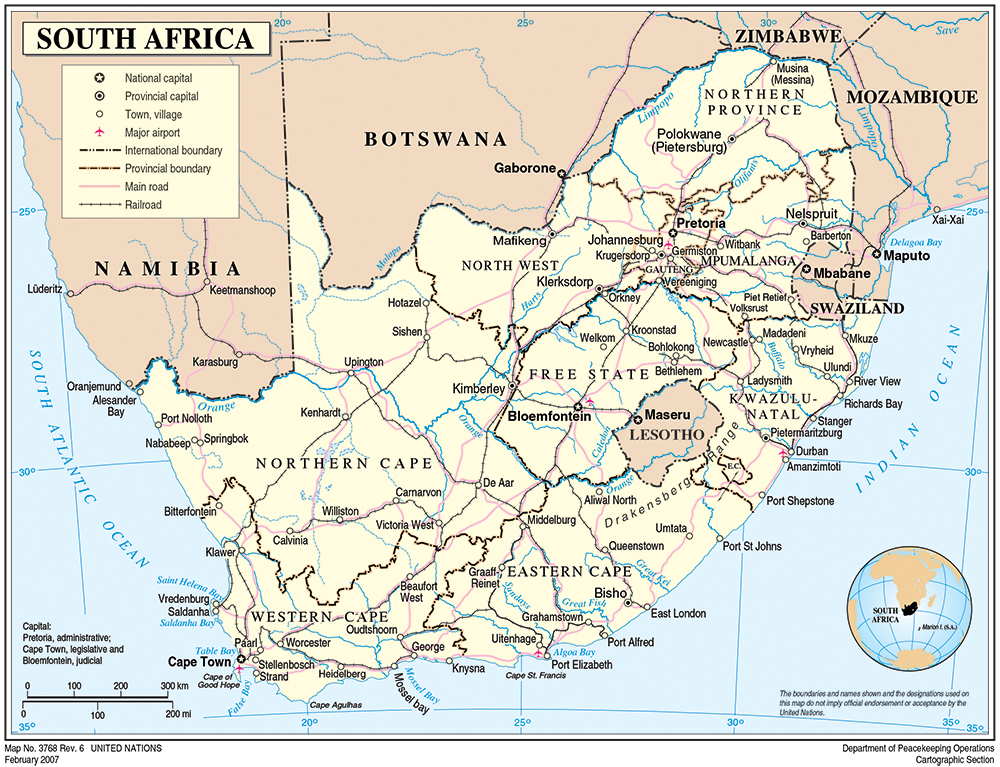

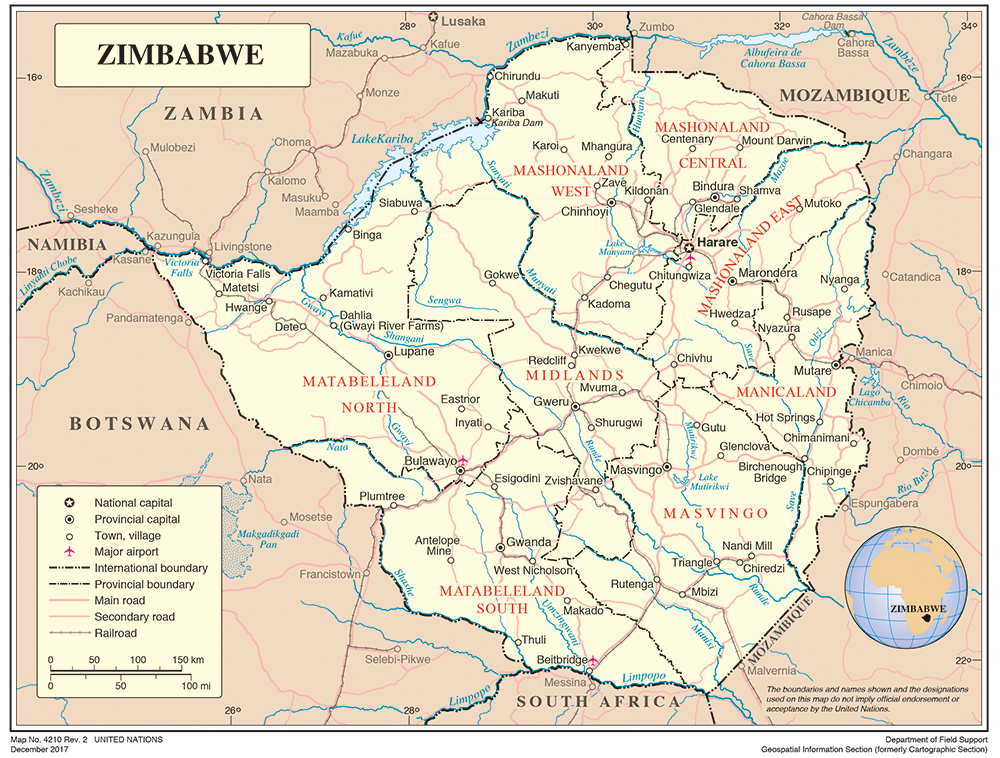

Human rights violations continue to dominate Zimbabwe’s social and political spaces. Despite being a signatory to continental and global human rights conventions, Zimbabwe’s commitment to human rights remains questionable. As there remains a rift between the African Union (AU), some member states and the International Criminal Court (ICC), the South African government tabled a motion in parliament to withdraw from the Rome Statute in October 2019. This followed an earlier attempt in October 2016 to withdraw, one year after the then AU chairperson, Robert Mugabe, insisted that its members must not cooperate with the ICC, as it was accused of being anti-African.1 South Africa initially rejected the call for non-cooperation but, in 2015, refused to arrest Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir, with the ICC’s powers of universal jurisdiction, signalling contempt of court.2 Given this context, this article contends that it will not be South Africans who will bear the consequences if the country eventually succeeds and withdraws from the ICC, but other African people living under regimes without good human rights records, such as Zimbabwe. While the dimension of South Africa’s geopolitical interests in Africa has sufficiently been analysed by Isike and Ogunnubi,3 I argue that the implications for human rights of the country’s withdrawal have not been exhausted.

South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC can have both negative and positive consequences for human rights in Zimbabwe. It could lead to more human rights violations in Zimbabwe, as South Africa might remain silent on issues of accountability on international crimes to win allies. However, South Africa could push for the ratification of the Malabo Protocol, as has been predicted,4 which would compel it to hold Zimbabwe accountable for human rights violations, with international crimes enunciated in the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR). The justification for linking South Africa’s withdrawal to Zimbabwe lies in the fact that whenever there is a crisis in Zimbabwe (persecution of human rights defenders, violence and economic collapse), many Zimbabweans seek refuge in South Africa. Victims without proper documentation face refoulement, often preceded by counter-accusations between the two states and less diplomatic commitment to address undocumented refugees.

The article proceeds with historical antecedents of international criminal trials and the ICC’s works in Africa since its conception. There is no shortage of literature in this area, but it helps to understand the background of South Africa’s willingness to cease to be a signatory of the Rome Statute. Following an analysis of South Africa’s grounds for leaving the ICC, the article discusses the implications for human rights in Zimbabwe – itself a signatory to the Rome Statute, but not a party member of the ICC. Zimbabwe benefits from South Africa’s involvement, largely due to the socio-economic and political ties that exist between these two southern African neighbours.

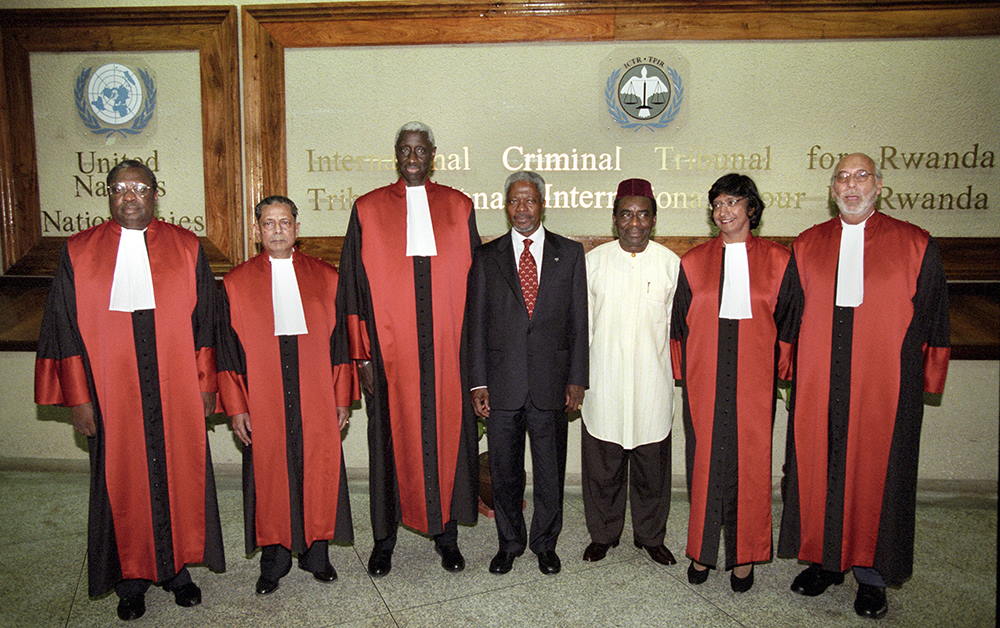

Historical antecedents of ICC trials

The ICC was preceded by ad hoc tribunals that were intended to hold perpetrators of human rights violations to account, following harrowing experiences of aggression and genocides. Serious human rights violations that were classified as international crimes were committed during the First World War and Second World War, and with genocides in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.5 The Nuremburg Trial and Tokyo Trial were designed to deal with the crimes of the Second World War following the conceptualisation of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, whilst the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 827 established the International Criminal Tribunal of the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to deal with the genocide that claimed thousands of lives during the ethnic conflicts which led to the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia.6 After the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established under UNSC Resolution 955.7 The key objective of these tribunals was to prosecute perpetrators of the genocides and war crimes so that such heinous crimes are never repeated, referred to by Mills as the “never again” stance of the UN on international crimes.8

For the UN and member states, the ICC was established as a permanent court – as opposed to the original ad hoc tribunals – to investigate and prosecute perpetrators of such crimes.9 The Nuremburg and Tokyo trials were established to address serious human rights violations in specific parts of the world. The ICC was largely concentrated in Africa during a period when most African leaders referred cases to the Court amidst serious violations during, and after, the third wave of democratisation. Of course, this does not mean that the ICC should not have acted in regions where international crimes were being committed.

ICC and Africa

As previously stated, there is no shortage of literature on the works and controversies of the ICC in Africa. The court’s record gives a sense of why South Africa is determined to withdraw its membership. At the outset, it is important to underscore that the mandate and scope of the ICC regards it as a court of last resort, as it can only prosecute if national courts are unwilling or unable to, or if the ICC is invited to by a country to do so.10 As such, in 2003, the government of Uganda referred cases in northern Uganda, involving Lord’s Resistance Army leaders Joseph Kony and others. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) did the same in 2004, resulting in arrests in the eastern part of the country, while the Central African Republic (CAR) followed with a referral in 2005 leading to the pre-trial detention of former vice-president, Jean-Pierre Bemba.11 Drexler added that these cases were less controversial because they originated from incumbent governments. But things turned controversial when the UNSC requested that the ICC indict al-Bashir in connection with the Darfur atrocities. Many scholars agree that until the attempted indictment of al-Bashir, African governments who had referred cases to the Court wanted to take advantage of incumbents to reign over political opponents. The furore originated from the long pursuance of al-Bashir, followed by Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta. This posed a threat to other African ruling elites as they could also be indicted, and they thus coalesced to withdraw from the Rome Statute.

From a transitional justice and legal perspective, when the ICC was invited to investigate, there was an acknowledgement that heinous crimes were committed and that perpetrators were expected to account for their atrocities. This does not regard whoever holds power, but who was responsible for the crimes committed. Although some African governments did not like the idea of the UNSC inviting the ICC to Sudan, the harrowing conflict experiences in Darfur were real and the atrocities could not be ignored. The UNSC itself is often accused of being anti-African, as the permanent member league of five excludes any African states. If the ICC is still being accused of being anti-African, then the December 2019 declaration by the prosecutor general to open investigations of war crimes between Israel and Palestine might change such perceptions. The prosecutor said: “I am satisfied that… war crimes have been or are being committed in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the Gaza strip.”12 Such developments might quash allegations that the ICC is anti-African. The closest meaningful explanation would be that the ICC was invited to Africa when serious crimes were being committed there. Its progression towards the Middle East and Asia shows some degree of concern for human rights violations, regardless of location.

The Malabo Protocol

In 2014, the AU adopted the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to extend its jurisdiction to crimes under international law and transnational crimes.13 Amnesty International acknowledged that the contents of the Protocol are praiseworthy, with the inclusion of respect for human rights, sanctity of life, rejection and fighting impunity, peace, stability and the prevention of serious crimes seen as progressive.14 It is important to note that the AU accelerated its efforts to ratify the Protocol following the warrants of arrests against al-Bashir, Kenyatta and William Ruto, among other sitting leaders, giving an impression that the ACJHR would replace the ICC in Africa to make sure that sitting presidents are not indicted. This departure would more likely extend impunity, given that more often than not, incumbents, with state power behind them, are usually the perpetrators of heinous human rights violations. However, it might be premature to conclude that it will be difficult for the ACJHR to address human rights violations without the indictment of heads of states.

South Africa’s mooted withdrawal from the ICC

South Africa intends to withdraw from the ICC because it claimed that “the ICC was incompatible with its efforts to mediate peace in Africa”.15 The South African government also stated, in its withdrawal notification, that “the ICC as a judicial body has lost its credibility because of its relationship with the UNSC and also because of perceived focus on African states notwithstanding the clear evidence of violations outside Africa”.16

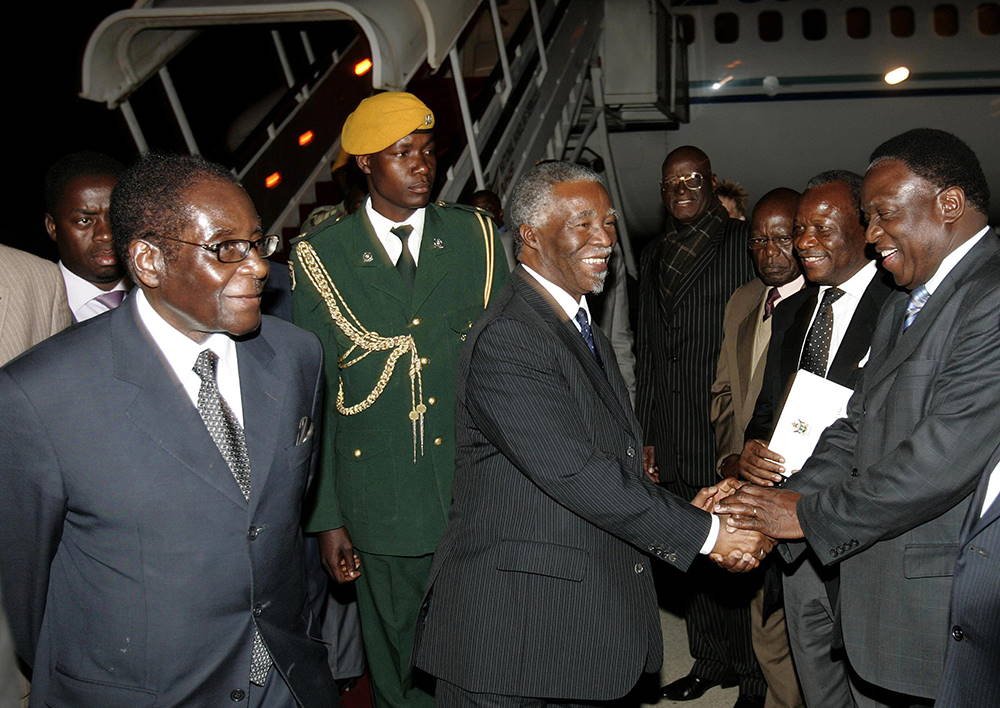

Some see economic interests as a primary reason for why South Africa wants to leave the ICC. As Africa’s economic giant, many countries would be expected to support South Africa’s interests. However, South Africa has also long been accused of being “condescending to other African countries, rendering its attempt to assume the moral high ground regarding the ICC patronizing at best”.17 It would be interesting to see how African nations react to the withdrawal of their so-called “patronizing friend”. South Africa may also want to prove that it can impartially mediate peace in Africa. Of course, the country previously deployed peacekeeping missions in the DRC and the CAR, among others, after the ICC had already started prosecuting in Africa. This suggests that South Africa can still be effective in mediating conflicts in Africa with the ICC present. South Africa mediated between political parties in Zimbabwe in 2008 to bridge the worsening human rights situation following a disputed election, but its stance on accountability for human rights violations committed was not clear. This could be the reason why Isike and Ogunnubi concluded that South Africa’s intentions are centred around winning back African trust.

South Africa, Zimbabwe and withdrawal from the ICC

When post-electoral violence broke out in Zimbabwe in 2008, the then South African president, Thabo Mbeki, played a crucial role in brokering dialogue between political parties that had participated in the election. On the economic front, Zimbabwe gets 49.4% of its total imports from South Africa, making South Africa Zimbabwe’s largest trading partner.18 The two countries share economic and political interests in the region. A crisis in Zimbabwe – be it humanitarian or human rights violations – therefore affects South Africa, too. Mbeki returned to Zimbabwe in December 2019 to persuade political parties to talk and to halt the worsening human rights, economic, social and political crisis. These relations could imply that Zimbabwe would support its neighbour’s intent to leave the ICC. However, such support could have unforeseen consequences for Zimbabwe’s own human rights situation.

For South Africa to argue that the ICC’s work in Africa is not compatible with its mediation efforts in Africa is confusing, given that South Africa was one of the countries which played a critical role in conceptualising the ICC informally before 1998, as it was determined to avoid the horrors of apartheid.19 As South Africa is seen as a leader in many regards, including having a progressive bill of rights and hosting world-class sports events and global political leader forums, for example, its move might lead to massive African withdrawals from the ICC.20 Amnesty International went further to predict that this may lead to impunity through the Court of Justice and Human Rights.21 The rights watchdog believes that African leaders will not want to see fellow sitting leaders being prosecuted if Africa finally leaves the ICC. With Zimbabwe’s non-membership in the ICC, it is possible that South Africa may not hold its neighbour accountable in the event of human rights violations. It did not speak boldly against massive military shootings in the aftermath of the 2018 elections, neither did it rebuke the same in January 2019. For a country as isolated from the international community as Zimbabwe, when South Africa remains silent, human rights defenders and citizens may suffer. For South Africa, the goal might be to retain Zimbabwe as a geopolitical partner in its bid to be a continental leader at all costs, possibly jeopardising the security of defenceless citizens in the process. Human rights could be sacrificed to preserve the strong economic ties that exist between the two countries.

However, South Africa has been touted as a progressive human rights nation. Its withdrawal from the ICC does not totally cast doom on its northern neighbour. South Africa may push for the ratification and operationalisation of the ACJHR – which, on paper, is a progressive document just like the Rome Statute, encapsulating international crimes. While human rights organisations22 warned that impunity to the same leaders who are responsible for heinous crimes might be the greatest undoing of the mooted ACJHR, the court may be effective in ending human rights violations in Africa through various peer monitoring mechanisms.

African luminaries such as Mbeki and Mahmood Mamdani have been advocating for political processes to end conflicts and human rights violations, as opposed to courts.23 In this vein, South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC could present an opportunity for the country to lead in domesticating peacebuilding mechanisms that are supported by the AU’s Peer Review Mechanism (PRM) and, more specifically, the Transitional Justice Policy (TJP) that was adopted in February 2019. The PRM encourages member states to assess each other in areas of democracy, human rights and other related issues, although some scholars criticise it for being Eurocentric. Having mechanisms such as the ACJHR, PRM and TJP could mean more support to grassroots conflict transformation and human rights initiatives. Objective 2 of the TJP clarifies that it is “an African model and mechanism for dealing with not only the legacies of conflicts and violations, but also governance deficits and development with a view to advancing the noble goals of the AU’s Agenda 2063, The Africa We Want”.24 While this might be a cryptic acknowledgement of the continental body’s failure to address past violations adequately, there is renewed resolve to address them the African way, without advancing impunity. The implementation of the TJP by member states will stand the test of time. With the TJP in place, South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC could be an opportunity to help fledgling democracies such as Zimbabwe to uphold human rights. With an ACJHR that may be headquartered or have a regional office in South Africa, Zimbabwe’s human rights record might improve. It is likely that there will be more international attention and focus by South Africa on human rights issues, and therefore the encouragement of adherence to the provisions of the ACJHR for countries such as Zimbabwe.

Conclusion

The ICC still has much to prove in that it is not anti-African, by investigating cases outside Africa. That it has started hearing cases in Myanmar, and has indicated that it would soon investigate Israel and Palestine for possible war crimes, is a step in the right direction. It may have come too late, pushing countries such as Burundi, The Gambia, Kenya and South Africa to seek withdrawals. South Africa, seen as an economic and political giant in the continent, believed that its efforts to mediate peace were being thwarted by the ICC. Accordingly, it might rigorously campaign for the ratification of the Malabo Protocol, which would give powers to the ACJHR to address international crimes with home-grown approaches. For Zimbabwe, its human rights record could improve, given that the ACJHR will be closer to home and will also inculcate African ways of transitional justice and accountability. However, it must be cautioned that if political and economic interests are prioritised over accountability, South Africa’s possible withdrawal from the ICC could lead to more human rights violations and impunity in Zimbabwe, which remains a signatory but non-party member to the ICC.

Endnotes

- Mangu, Andre Mbata (2015) The International Criminal Court, Justice, Peace and the Fight against Impunity in Africa: An Overview. Africa Development, 40 (2), pp. 7–32.

- South Africa refused to arrest Omar al-Bashir with powers of universal jurisdiction issued by the ICC when he visited the country in 2015 in connection with the Darfur atrocities.

- Isike, Christopher and Ogunnubi, Olusola (2017) The Discordant Soft Power Tunes of South Africa’s Withdrawal from the ICC. Politikon, 44 (1), pp. 173–179.

- In 2014, the AU adopted amendments to include international crimes in the African Court.

- Imoedemhe, Ovo Catherine (2017) Complementarity Regime of the International Criminal Court. Cham: Springer, pp. 10–17.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mills, Kurt (2012) Bashir is Dividing us: Africa and the International Criminal Court. Human Rights Quarterly, 34 (2), pp. 404–447.

- Ibid.

- Drexler, Michael (2010) Whither Justice: Uganda and Five Years of the International Criminal Court. Interdisciplinary Journal of Human Rights Law, 5 (1), pp. 97–106.

- Ibid.

- Trew, Bel (2019) ‘Israel Set to be Investigated for War Crimes in Palestinian Territories, ICC Announces’, Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/israel-war-crime-palestine-icc-hague-netaynahu-idf-investigation-a9255246.html> [Accessed 3 January 2020].

- Amnesty International (2016) Africa: Malabo Protocol: Legal and Institutional Implications of the Merged and Expanded African Court. Amnesty International, 22 January. Index number: AFR 01/3063/2016.

- Ibid.

- Essa, Azad (2016) South Africa’s Withdrawal from the International Criminal Court Reeks of Hypocrisy. Washington Post, 26 October.

- Ssenyonjo, Manisuli (2018) State Withdrawal Notifications from the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: South Africa, Burundi and the Gambia. Criminal Law Forum, 29 (1), pp. 63–119.

- Ibid.

- globalEDGE (n.d.) ‘Zimbabwe Trade Statistics’, Available at:<https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/zimbabwe/tradestats/> [Accessed 14 January 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- African Union (2019) ‘African Union Transitional Justice Policy’, Available at: <https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=A0geK9n4aYBeltIAvhdXNyoA;_ylu=X3oDMTEycm81cXI4BGNvbG8DYmYxBHBvcwMxBHZ0aWQDQjk1MzZfMQRzZWMDc3I-/RV=2/RE=1585502841/RO=10/RU=https%3a%2f%2fau.int%2fen%2fdocuments%2f20190425%2ftransitional-justice-policy/RK=2/RS=XkdFzn0zL9cQqHJMHfpCz09Azc4-> [Accessed 9 January 2020].