Introduction

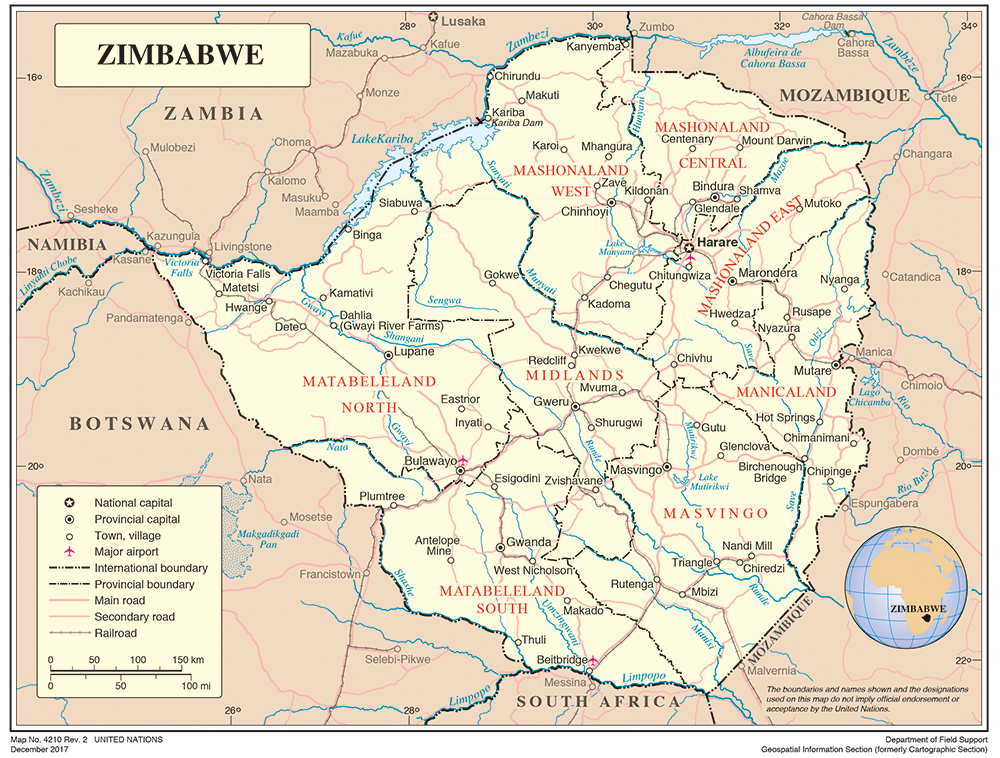

Electoral disputes have long played a role in directing political conflicts towards the attainment of ephemeral peace in both Zimbabwe and Lesotho – two countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. Zimbabwe’s Global Political Agreement (GPA) helped to end conflict in the country, further establishing a government of national unity (GNU) with institutional mechanisms and conditions that enabled transition to a more peaceful context. A decade later, Zimbabwe is still at a crossroads, facing almost the same political and economic hardships that it did in 2008, when the GPA was signed. The current political stand-off between the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) is a manifestation of the deep-seated political problems in the country, and proof that the GNU did not enable lasting solutions to Zimbabwe’s politico-economic crisis.

Lesotho has had three consecutive GNUs since 2014. The first two GNUs barely lasted two years beyond their dates of constitution, while the third is already presenting signs of possible disintegration. The examples from these two countries prove the need to reconceptualise GNUs as a strategy for lasting conflict resolution in Africa. This article establishes the sources of disharmony among GNU parties, using the cases of Zimbabwe and Lesotho.

A GNU is a power-sharing government comprising of major political parties that coalesce their efforts to end conflict, and is designed specifically to accommodate all opposing political players to participate in government structures.1 The assumption is that the equitable participation of the different contenders will diminish the potential for conflict and enhance the prospects for good governance, development, integration and effective delivery of social goods to citizens. GNUs are preceded by peace agreements that set the framework for their creation and for monitoring success. As part of the post-conflict reconstruction system, GNUs have five dimensions that can be programmed to cumulatively inform sustainable peace, and these are political transition, inclusive participation, human rights, rule of law and resource mobilisation.2

Where they are properly instituted, GNUs potentially enable various political parties to bury their political differences and strive to build democratic societies. Wrongly instituted GNUs, on the other hand, can be delicate and discordant transitional institutions with the potential to disintegrate and create more political strife. Given the varied historical experiences of African countries and the limited support available to propel GNUs to viability for effective conflict transformation, it can be argued that the establishment of GNUs should be regarded as an exception only to applicable contexts, rather than a norm to all contexts.

Mapuva opines that political rivalries have the potential to bury the hatchet and work together for the common good of the nation in a GNU.3 Matyaszak, on the other hand, describes a GNU as a tool adopted to effect relief from conflict and suspend hostilities among raging political and non-political actors.4 In essence, the level at which a GNU accommodates various players for participation – including civil society, civil service and women’s groups – determines its levels of success. This article further argues that GNUs can be effective for lasting conflict transformation only if their parameters of operation are more an outcome of decisions by local actors as opposed to being impositions by external actors such as regional bodies, global bodies and external mediators.

Zimbabwe

The Zimbabwean GNU was born in 2009 on the basis of the GPA. Although there are different interpretations of the causes of the Zimbabwean conflict that culminated in the violence of 2008, there is inherent consensus that structural causes – mainly highlighted as land and property rights issues –triggered this conflict.5 The formation of the MDC in the same period pitted it against ZANU–PF by virtue of its funding modality from the West, as well as its ideological stance against the land reform exercise. As such, conflict ensued.

The SADC mediated the Zimbabwe conflict cumulatively, starting in 2000 when it mandated former presidents Thabo Mbeki (South Africa), Joaquim Chissano (Mozambique) and Sam Nujoma (Namibia) to engage Robert Mugabe, then president of Zimbabwe, on the effects of the land reform process on the country’s economy in the face of foreign-imposed sanctions and donor fatigue. These mediation efforts led to relatively credible harmonised parliamentary and presidential elections in 2008. The elections did not result in a clear winner, igniting further violence and a call for a rerun. This led to the constitutional amendment that was adopted as an outcome of the SADC mediation process, requiring the winning presidential candidate to have 51% or more of the vote.

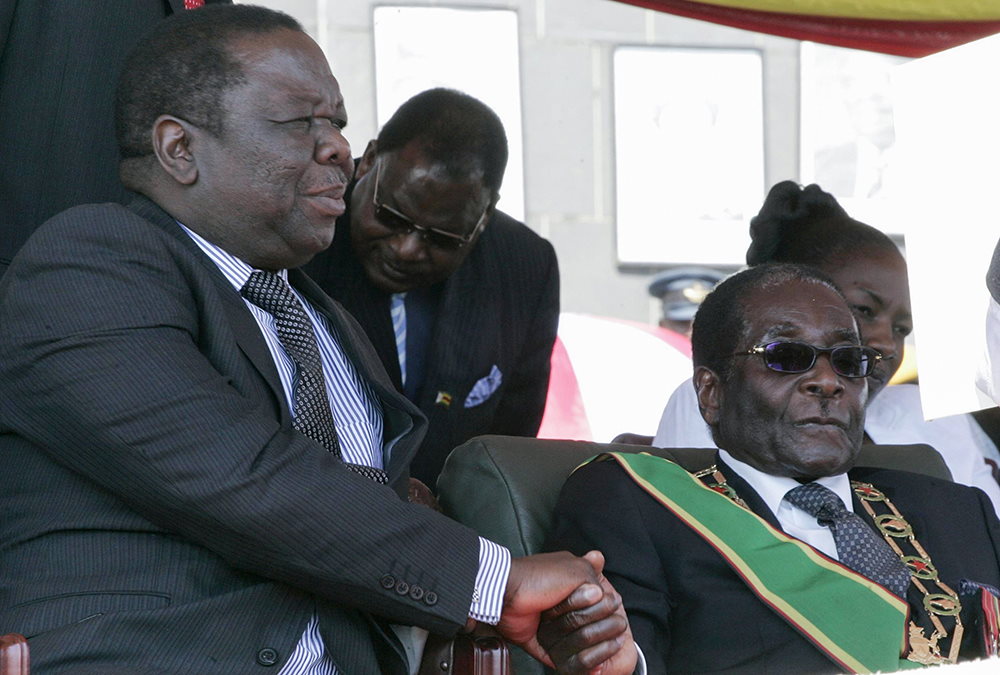

The election rerun, held in June 2008, was tainted by allegations of electoral flaws, entrenched institutionalised violence and a regression into violence, prompting the SADC to mandate Mbeki to facilitate interparty negotiations for a political solution among the key political players. The mediation concluded in September 2008 with the signing of the GPA and the formation of a GNU, comprising ZANU–PF and two MDC formations.

The Zimbabwean GNU achieved a number of successes when it was implemented. First, it prevented the country from descending into chaos, thereby altering the enemy images among the political parties, ZANU–PF and the two MDC formations.6 Second, the institutionalisation of a national infrastructure for peacebuilding through the Organ on National Healing, Reconciliation and Integration (ONHRI) and the Joint Monitoring and Implementation Committee (JOMIC) provided the building blocks for an ephemeral peace in the country. The work of the ONHRI and the JOMIC in the various communities influenced the elimination of the then-existing direct forms of violence, paving the way for the institutionalisation of reforms in the political and economic spheres in the country. Article 7 of the GPA also provided for gender equality in peacebuilding processes.

Economically, the Zimbabwean GNU was established at a time when the country was facing hyperinflation, a sustained period of negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates, and massive devaluation of the currency. Article 31(a) of the GPA prioritised the restoration of economic stability and growth in Zimbabwe. The Government of Zimbabwe came up with two Short-term Emergency Recovery Programmes: STERP 1 and STERP2. Between 2009 and 2012, following the introduction of these two economic policies, the economy rebounded, registering significant growth averaging 10.5% per annum.7

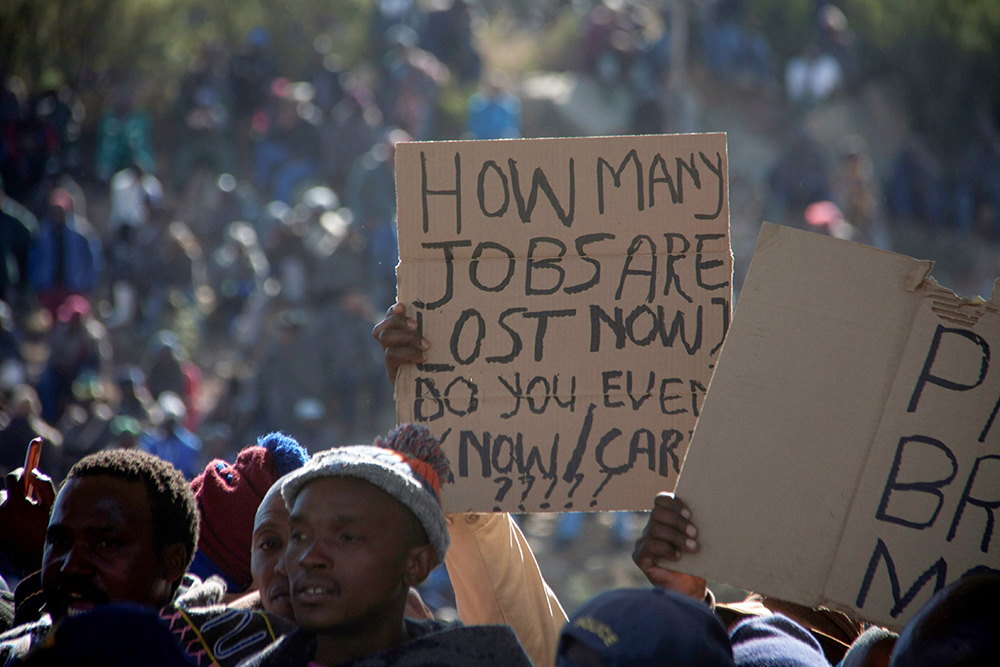

Contrary to the highlighted achievements, a number of conflict undercurrents among the political parties resulted in disagreements and disengagements among the government’s key actors. This indicates that the Government of Zimbabwe failed to effect complete conflict transformation in the country. Socially, citizens continue to suffer massive water and power cuts, poor health facilities, the collapse of the manufacturing industry and a skills flight, five years after the implementation of the GNU.

Politically, leaders from all parties focused more on political partisanship and self-aggrandisement at the expense of improving the economy. The GNU Cabinet included 41 ministers – a rise from the former composition of 31 ministers8 – prompting overexpenditure on salaries and related packages. The appointment of the attorney general before the installation of the MDC’s Morgan Tsvangirai was also a violation of the GPA, which provided for the prime minister to be appointed before the appointment of the attorney general. This showed a disregard for the rule of law, even at the onset of the GNU.

The power tug-of-war between Mugabe and Tsvangirai is enough proof of failure of political leaders to move their political interests from the individual to the collective. Mugabe refused to cede power to Tsvangirai, offering him the position of third vice president – while, on the other hand, Tsvangirai was adamant that he would accept nothing less than the position of prime minister with full executive powers in a two-year transitional government.9

Lesotho

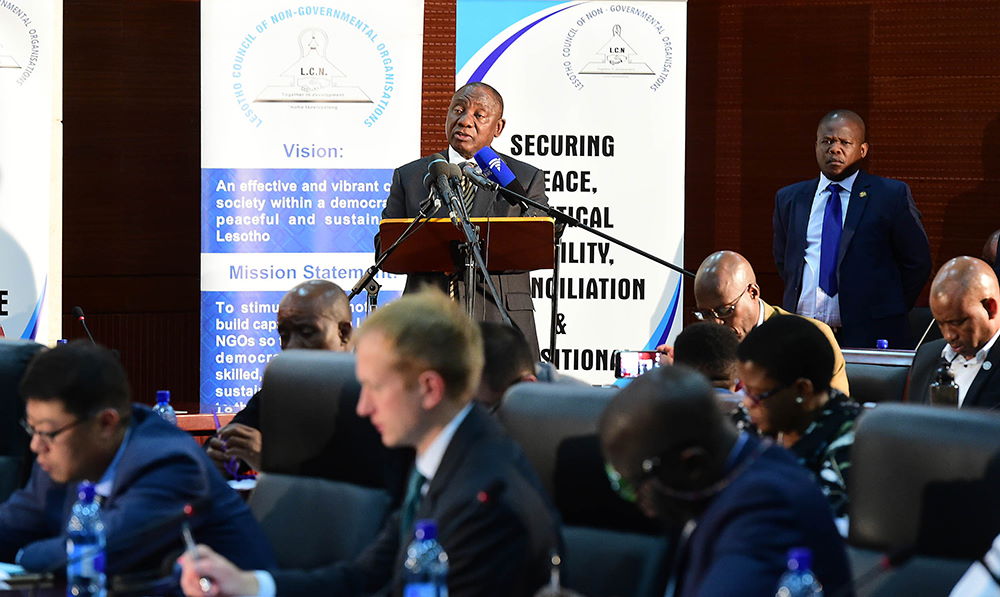

Lesotho held its third election in five years in June 2017 – a sure sign of deep-seated instability in this mountain kingdom. This election was triggered by a vote of no confidence against Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili, which was passed in March 2017. Instead of resigning, Mosisili advised the king to call for snap elections – in which his opponent, Thomas Thabane of the All Basotho Convention, emerged as the winner of 48 parliamentary seats, but short of the 61 needed to form a government.10 According to the Constitution of Lesotho, when a motion of no confidence against the government and the prime minister succeeds in Parliament, the incumbent has to resign within three days or advise the king to call for elections. The parties later agreed to form a coalition government.

Effectively, Lesotho has had three governing coalitions since 2014, all of which have failed to last beyond the first two years of their supposed five-year terms. The first coalition – made up of the All Basotho Convention, the Lesotho Congress for Democracy and the Basotho National Party – collapsed in 2014 after only two years. This was followed by the February 2015 snap elections that ushered in the Mosisili-led seven parties’ coalition, thereby removing Thabane from power. The Mosisili-led coalition gave way to the current coalition after the June 2017 elections.

The current GNU in Lesotho has succeeded in transforming the political character of the Basotho from that of strife among the political parties, enabling them to work together to achieve peace for the first time in history. The fact that Lesotho, with a population of fewer than 2 million people, has had a significant number of political parties, is a sign of the political discord that exists. However, the ability to form a coalition government without receding into escalating conflict signifies a positive outcome of the current GNU.

There are, however, major issues of discontent among the citizenry over Thabane’s links to the Chinese, who now dominate the business space and possess more business contracts than local businesspeople in Lesotho. The current GNU is also accused of the mismanagement of state funds, corruption and a failure to provide employment and social services, such as health and education.

Politically, there are huge cracks in the current coalition, with Keketso Rantšo of the Reformed Congress of Lesotho alleging that her political party members have been sidelined for appointment to strategic political positions in the country. Thus, the GNU framework in Lesotho lacks a strategy for distributing power equally to all participants to ensure lasting peace. The major political parties exercise more power and control over the minor political parties when it comes to decision-making in the GNU. This situation is not peculiar to Lesotho alone – in the Zimbabwean GNU, Mugabe remained with his executive powers afforded to the presidency, and had no legal binding basis to consult Tsvangirai on appointments. For example, Mugabe’s appointment of eight retired military officials to positions in the Information and Publicity Ministry showed not only his close connection to the military but also the powerlessness of the MDC as a party to the GNU.11

Political analysis of Lesotho’s lack of GNU arrangements claims that whilst the conflict situation in Lesotho is fertile ground for the success of a GNU, the failure of coalition governments emanates mainly from a lack of congruency among the political leaders involved. Political leaders often fail to ensure fulfilment of the requirements of GNU frameworks, as well as to live up to their promises to deliver social goods to citizens.

Conclusion

Among other issues, this article demonstrates that although the GNUs in both Zimbabwe and Lesotho brought some positive developments in solving political stand-offs among rival political parties, issues of unequal power-sharing between the bigger political parties and the smaller ones remained a key challenge. This led to strained relationships between and among the political parties, and ruined prospects for positive peace post-GNU in both countries. Success of any GNU’s post-conflict reconstruction system is determined by the interaction of the specific internal and external actors present, coupled with a good understanding of the history of the conflict and the GNU framework. Furthermore, GNUs in Africa are often affected by endogenous forces, as their evolvement is often preceded by external mediation outcomes that enforce mediation before conflicts reach a hurting stalemate, breeding half-baked peace agreements. In Zimbabwe, the collapsing economy and associated violence triggered international isolation and constant calls by the SADC for the parties to dialogue peacefully to save the region from economic and political problems. Lesotho has been strong in refusing the imposition of GNUs by outside mediators. The country’s major challenge has been the failure to transcend the individual political interests of the political parties for common good.

GNUs in Africa are dominated by the interests of the leading political stalwarts, often ignoring the voices of local actors such as civil society organisations, including women’s groups, churches, traditional authorities; as well as, other minor political parties. As a result, political leaders often fail to understand the needs and aspirations of many, leading to incongruence and the collapse of their political agreements. In both Zimbabwe and Lesotho, GNU formation and implementation remained the preserve of formal politicians, without giving regard to the roles that regular citizens and civil society can play.

Endnotes

- Mukoma, Wa Ngugi (2008) A Caricature of Democracy: Zimbabwe’s Misguided Talks. The International Herald Tribune, 25 July.

- Hoste, Jean-Christopher and Anderson, Andrew (2010) Dynamics of Decision Making in Africa. Leriba Lodge, 8–9 November 2010, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Mapuva, Jephias (2010) Government of National Unity as a Conflict Prevention Strategy: Case of Zimbabwe and Kenya. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12 (6), pp. 247–263.

- Matyszak, Derek (2010) Law, Politics and Zimbabwe’s Unity Government. The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

- Raftopoulos, Brian (2011) The Global Political Agreement as a ‘Passive Revolution’: Notes on Contemporary Politics in Zimbabwe. Solidarity Peace Trust.

- Ibid.

- Nyarota, S., Kavila, W., Mupunga, N. and Ngundu, T. (2015) An Empirical Assessment of Binding Constraints to Zimbabwe’s Growth Dynamics. RBZ Working Paper Series, 2.

- Cheeseman, Nic and Tendi, Blessing-Miles (2010) Power‐sharing in Comparative Perspective: The Dynamics of ‘Unity Government’ in Kenya and Zimbabwe. Journal of Modern African Studies, 48 (2).

- Hartwell, Leon (2013) Reflecting on Positive Zimbabwe GNU Moments. The Independent, 11 July.

- Theko, Tlebere (2019) ‘The Congruency of Government of National Unity’, 13 July, Available at: <https://www.nwlesotho.co.ls/the-congruency-of-government-of-national-unity/> [Accessed 12 December 2019].

- Cheeseman, Nic and Tendi, Blessing-Miles (2010) op. cit.