Introduction

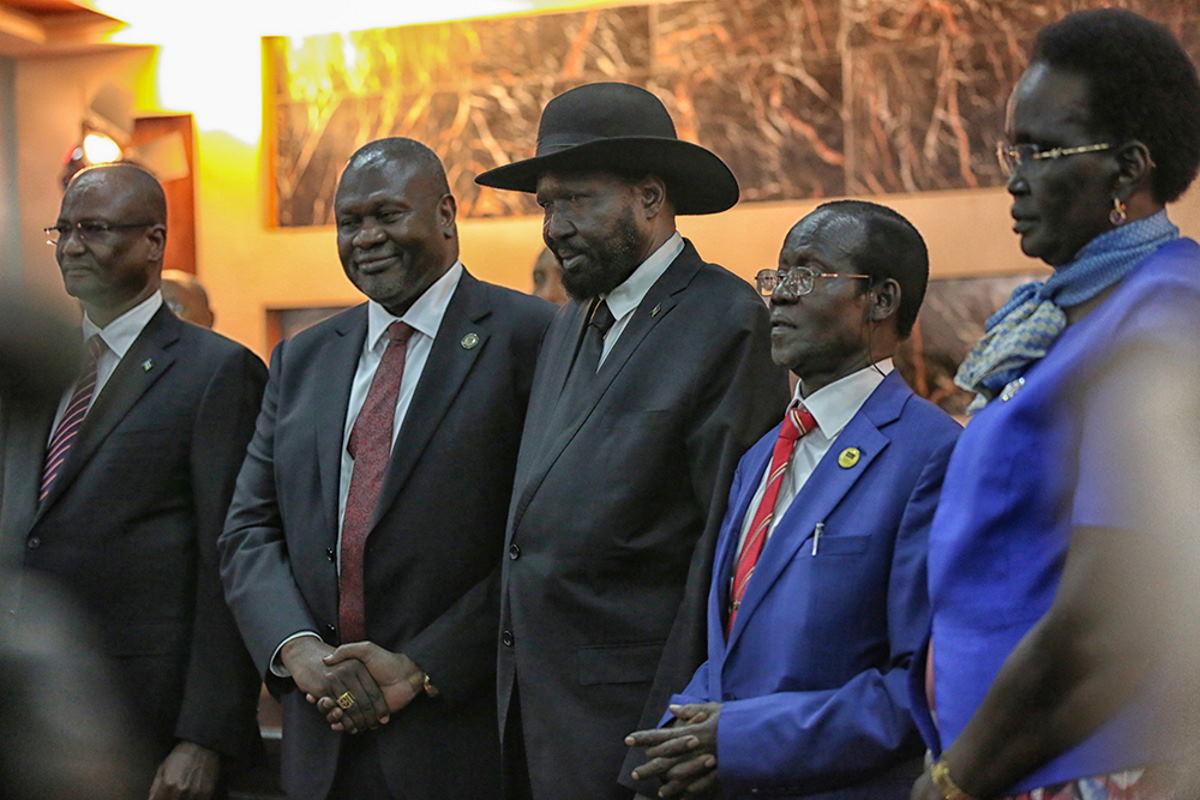

On 22 February 2020, South Sudan formed the Revitalized Transitional Government of National Unity (RTGoNU), which had long been provided for under Chapter 1 of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS), signed between the government and opposition political parties on 12 September 2018 in Addis Ababa. The RTGoNU, led by Salva Kiir Mayardit as the president, saw the swearing in of the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO), Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon, as the first vice president. Four other vice presidents were also sworn in: James Wani Igga (second vice president, from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/SPLM), Taban Deng Gai (third vice president, from SPLM-IO), Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior (fourth vice president) and Hussein Abdelbagi Akol Agany (fifth vice president, from the South Sudan Opposition Alliance/SSOA). On 12 March 2020, as part of the RTGoNU, the president appointed 10 deputy ministers and 35 members of the Council of Ministers. The unity government will also comprise 550 members of parliament, 10 governors and three area administrators. The formation of the RTGoNU was finally realised 18 months after the signing of the R-ARCSS, following mediation efforts led by the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the deputy president of South Africa, David Mabuza, as parties continued to miss deadlines agreed both in the R-ARCSS and through mediation. While South Sudan, its neighbours and the international community may be celebrating the formation of the RTGoNU as an opportunity for renewed hope and another chance to restore peace, security and stability in a country that has witnessed intermittent conflict since it seceded from Sudan in July 2011, it is equally important to have an understanding of the huge task and responsibility (as well as the accompanying challenges) ahead of the RTGoNU in finally delivering a united, peaceful and prosperous society. This is what this article presents and analyses.

Background

The RTGoNU formed on 22 February 2020 was an unfulfilled provision of the R-ARCSS signed by warring parties in South Sudan on 12 September 2018. It was designed to revive the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) of 17 August 2015, which was meant to bring an end to the civil war that erupted on 13 December 2013 in the country.

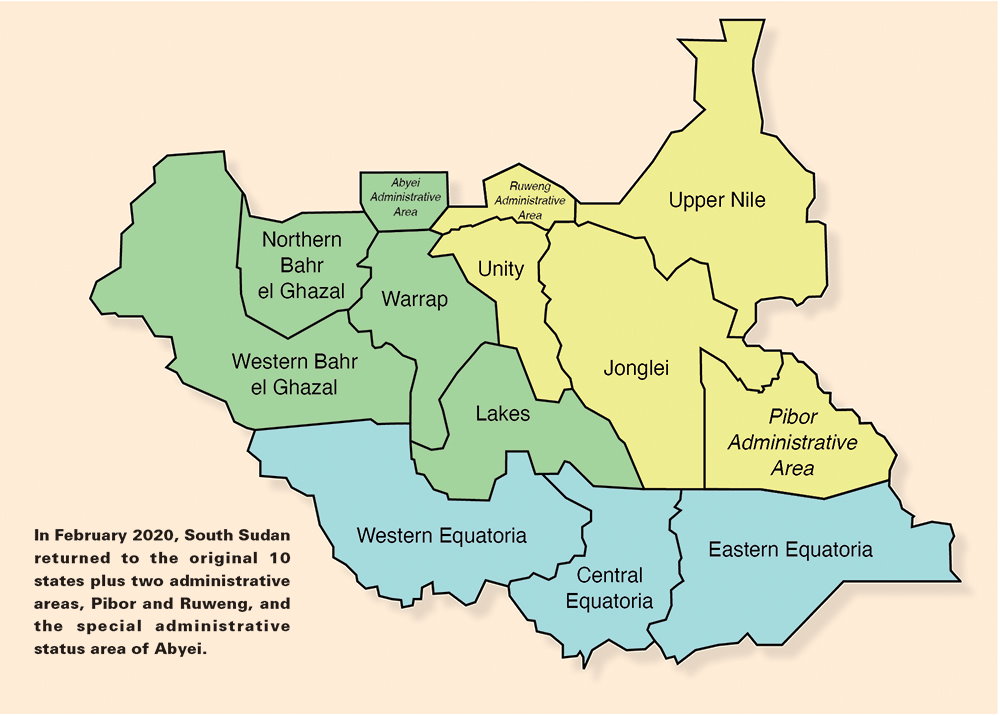

Since the signing of the R-ARCSS, Machar expressed his unresolved issues, which he demanded that Kiir address before Machar agreed to be part of the RTGoNU. There were several meetings mediated by the IGAD, with the main contentious issues revolving around the reduction of the number of regional states – which stood at 10 at independence in 2011 and were increased to 28 in 2015, and further increased to 32 in January 2017. Other issues included security arrangements, governance issues and the integration of fighting forces.1 On the issue of regional states, Kiir had previously insisted on maintaining the 32 regional states on the premise that it allowed for the devolution of power, governance and resource mobilisation, as opposed to centralising governance in Juba. However, he later compromised to return the regional states to the pre-2015 arrangement of 10 states, although three administrative areas were added. There was no progress on the integration of forces into a unified trained national army, as agreed under the R-ARCSS. Specifically, Machar and other opposition parties expressed displeasure at Kiir’s disbursement of less than US$30 million of the US$100 million pledged towards the implementation of the R-ARCSS, arguing that in the absence of a trained unified national army, the country would relapse into full-scale conflict.2 Another issue that was outstanding related to Machar’s personal security, although it was finally agreed that Kiir would take over this responsibility.

Having been a product of compromises on politically sensitive issues around the demarcation of regional states, security arrangements, governance, personal security and integration of forces, the formation of the RTGoNU on 22 February 2020 can be considered as a golden opportunity and viable option to usher in peace in South Sudan. With South Sudanese and the broader international community having travelled a long journey, mired with devastating conflicts and interrupted by episodes of short-lived relative peace since independence in July 2011 (see Table 1 below), there are high hopes that the RTGoNU will deliver. It is undeniable, however, that the road ahead for the RTGoNU will be bumpy, due to a profusion of challenges that are political, socio-economic and technical in nature.

Table 1: The Nine-year Road to Peace in South Sudan, from January 2011 to February 2020

| February 2020 | The RTGoNU formed. Machar reappointed (for the third time since independence) as first vice president, with other four vice presidents also appointed. |

| November 2019 | The day set to form the RTGoNU was 12 November 2019. This was a failure, as Machar and Kiir could not agree on outstanding issues. IGAD extended the deadline by 100 days and continued to mediate negotiations. South African vice president, David Mabuza, also contributed to the mediation process as President Cyril Ramaphosa’s special envoy to South Sudan. |

| September 2018 | The R-ARCSS was signed between the government and opposition parties to revive the ARCSS. Machar delayed his return to Juba from exile over outstanding issues. This further delayed the full implementation of the powersharing agreement. |

| July 2016 | Kiir and Machar’s bodyguards engaged in a shootout at a press conference in Juba, and subsequent clashes occurred across the city. Machar fled into exile in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), then South Africa and later in Sudan. |

| April 2016 | Machar was reappointed into government (for the second time since independence) as vice president. |

| August 2015 | The ARCSS peace agreement was signed between the government and opposition. |

| December 2013 | President Kiir fired Machar as vice president, accusing him of attempting a coup d’état. There had been a political power struggle between Kiir and Machar. |

| July 2011 | South Sudan declared independence, after 98.83% of the population voted in favour of secession/independence from Sudan in a referendum held between 9 and 15 January 2011. |

Key Priorities and Tasks of the Revitalized Transitional Government of National Unity

The principal task of the RTGoNU is to fully implement the R-ARCSS signed on 12 September 2018 in a way that restores permanent and sustainable peace, security and stability in South Sudan. The Transitional National Legislative Assembly (TNLA) has to be restructured and reconstituted. To ensure that the RTGoNU executes its mandate efficiently, economically and effectively, the presidium has to make sure that all the institutions provided for under the R-ARCSS are put in place with urgency and are consistent with the constitution and other relevant enabling legislations. According to the R-ARCSS, the RTGoNU was initially mandated to rule South Sudan for a transitional period of 36 months. Between now and the next elections, the RTGoNU is thus mandated to carry out the following activities, as provided for in Chapter 1 (Section 1.2):3

- facilitate the rehabilitation and reintegration of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and returnees;

- facilitate national reconciliation and national healing;

- complete the process of making a permanent national constitution;

- consolidate peace and stability in South Sudan;

- undertake public finance management radical reforms and transformation;

- ensure effective, transparent and accountable management of national resources;

- undertake radical civil service reforms;

- design and implement security sector reforms;

- rebuild and recover destroyed physical infrastructure;

- conduct a national population and housing census; and

- devolve powers and resources to state and local government levels.

Over and above these key priorities, the RTGoNU has to ensure that there is agreement and consensus in the full resolution of all outstanding issues that delayed the formation of the unity government. This will ensure that there is unity, harmony, cohesion, trust and political will in the RTGoNU, especially within the presidium and Council of Ministers.

The Road Ahead for the Unity Government: Challenges and the Way Forward

The execution of the key priorities and tasks of the RTGoNU will be difficult. The political and conflict history of South Sudan has shown that without adequate political will and the commitment to building lasting peace, stability and prosperity, opportunities are always lost as tensions are triggered by what appear to be minor disagreements among the top leadership, resulting in anarchy and conflict resurgence. This was the case in both December 2013 and July 2016, when conflict erupted as a result of disagreements between Kiir and Machar. The first task of the RTGoNU has to be that of resolving all outstanding issues that delayed the formation of the unity government. This task will be made difficult if the leadership in South Sudan decides to address these issues with the objective of consolidating political power and amassing political capital, instead of putting national development motives first.

The issue of reducing the number of regional states from 32 to 10 has already sparked disagreements and tensions. Whilst the 32 regional states have been reduced to 10 as agreed, the parties have since failed to reach an agreement on the allocation of the 10 states and the three administrative areas of Abyei, Greater Pibor and Ruweng. Whilst the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC) – which is mandated to monitor and oversee the implementation of the R-ARCSS – has attempted to mediate the impasse through interparty consultative meetings with all parties to the R-ARCSS since 27 March 2020, the parties failed to reach a consensus on how responsibility will be allocated at state and local government levels.4 Notwithstanding the lack of consensus, on 8 May 2020, Kiir proceeded to allocate the states, with six of these regional states (Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Warrap, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal and Unity) allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – in Government (SPLM-IG); three states (Jonglei, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria) allocated to Machar’s SPLM-IO, and Upper Nile State allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOP).5 This is already sparking conflict within the RTGoNU, as Machar and other opposition parties are contesting the unilateralism displayed by Kiir, arguing that the decision does not consider and acknowledge the relative prominence of the political parties within the respective states and administrative areas.6 It is such decision-making and problem-solving approaches that produce disunity and mistrust among parties to the R-ARCSS and in government. Moreover, the responsibility of sharing states should be motivated by the rationale to ensure effective decentralisation and devolution for better governance, rather than be driven by non-productive politics of power and control. The RTGoNU rests on a fragile unity of long-time political adversaries and antagonists. Therefore, rebuilding mutual trust, collegiality, confidence and coherence would require the presidium and ministers to ensure consensus and effective consultation before politically sensitive decisions are made.

Ending conflict and community tensions should be another priority for the RTGoNU. However, despite the existence of a permanent ceasefire agreement, intercommunal clashes persist. For example, at the end of April 2020, the RJMEC reported violent communal clashes, cattle raids and revenge attacks that resulted in massive deaths, injuries and destruction of property in areas such as Abyei, Greater Bahr el-Ghazal, Equatoria, Greater Upper Nile, Jonglei, Lakes and Unity.7 On 20 March 2020, the United Nations (UN) also reported that the Dinka Bor, Lou Nuer and Murle communities in the eastern and central parts of the country were engaging in escalated intercommunal fighting, with evidence suggesting that political and traditional leaders were instigating the clashes through mobilising armed youth and exploiting pre-existing communal tensions over access to natural resources (such as tensions over cattle movement, and access to water and grazing land), which left hundreds of people dead and thousands displaced.8 The RTGoNU has to bring an end to this conflict by addressing the root causes and ensuring justice, including restoring the rule of law and the effective functioning of regional states and local governments to deal with localised militias. It would be helpful for the RTGoNU to ensure the demilitarisation of all cities and villages, and the disarmament of civilians, as part of the critical R-ARCSS security arrangements.

Other contentious issues, such as the formation of a unified trained national army that integrates government soldiers with armed opposition fighters into a single national army, as agreed under Section 2.2.1 of the R-ARCSS,9 should be prioritised. It is commendable that there is already progress being made by the RTGoNU in this regard. By the end of April 2020, at least 78 500 troops had been registered at different cantonment sites, training centres and barracks for screening, so that they could be selected for training and redeployment to the envisaged Necessary Unified Forces (NUF), whilst over 45 000 troops from the government and the opposition were moved from cantonment sites to training centres to commence training and redeployment to the NUF, as provided for under the R-ARCSS.10 Related to the unification of forces and the training of Very Important Persons (VIP) Protection Forces, the RTGoNU has to undertake security sector reforms. These include implementing the disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) of forces through the DDR Commission and recently announced Transitional Committee for Coordination of the Implementation of Security Arrangements, as provided for under Chapter 2 of the R-ARCSS, to ensure that South Sudan has unified, stable, professional, cohesive, efficient, effective and well-governed security services. The DDR Commission is reported to have now drafted a revised DDR Strategic Plan and Programme, and plans are underway to establish eight DDR transit sites across the country.11

However, executing transitional security arrangements, including the unification of forces and security sector reforms, is undoubtedly an expensive undertaking, and challenges may be faced in raising a budget sufficient enough to cater for the material, logistical and technical expenses. For example, training and cantonment sites for screening, training and unification in Western Equatoria12 and Wau State13, which are hosting opposition troops and government-controlled South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF), are facing challenges in providing adequate food, water, sanitary services, medicines, other support facilities and dignity kits for female trainees, as they lack adequate funding.14 Raising the requisite resources requires reprioritisation, political will and commitment to the task.

The national reconciliation and national healing process continues to be undermined by limited progress in the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms, including the Hybrid Court of South Sudan (HCSS); the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing (CTRH); and the Compensation and Reparation Commission (CRC) provided for under Chapter 5.1 of the R-ARCSS. In the absence of strong institutions of justice and accountability, war crimes and human rights abuses persist. The UN Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan for the period between February and March 2020 notes that serious crimes and human rights abuses continue with impunity in South Sudan, including the forced recruitment of children into armed conflict, sexual and gender violence, abduction of women and girls, pillaging, destruction of property, and intentional starvation of civilians as a weapon of war.15 The RTGoNU has to attend to this with urgency, since genuine national reconciliation and healing, reparation and compensation are key in ensuring restorative and retributive justice to facilitate trust, peacebuilding and national unity whilst nurturing a culture of accountability, responsibility, rule of law and constructive politics. There is a high likelihood, however, that resistance from some elite politicians and army personnel will continue as they seek to evade prosecution, justice and accountability. Collective commitment and national consciousness, political energy and political will are essential to drive the process and progress in this regard.

The reintegration of IDPs and refugees, as well as national reconciliation and national healing, remain important tasks of the RTGoNU. Article 3.1.1.5 of the R-ARCSS provides that the rights and dignity of refugees and IDPs to being repatriated, protected, resettled, rehabilitated and reintegrated should be guaranteed. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that by 30 April 2020, refugees and asylum-seekers from South Sudan stood at 2 254 341 in Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, the DRC and Kenya, with over 75% of refugees in Uganda and Sudan.16 Related to this, the humanitarian situation has to be addressed in South Sudan. By March 2020, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that 52% of the South Sudanese population was suffering from severe acute food insecurity immediately after the harvest period as a result of conflict-related livelihood disruptions, climate shock, displacements and economic crisis.17 It was stated that between May 2020 and July 2020, an estimated 6.5 million people (55% of the national population) will be in severe acute food insecurity,18 with the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimating that about 1.3 million children below five years of age will be suffering from acute malnutrition.19 The situation is worsened by the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic. In a report on 17 April 2020, titled COVID-19: Protecting African Lives and Economies, the Economic Commission for Africa estimated that over 300 000 Africans may lose their lives due to COVID-19, adding that the pandemic may push close to 27 million people into extreme poverty. It thereby called for a US$100 billion stimulus package or health and social safety net for Africa at a time when the majority of African economies are already struggling.20 As of 7 June 2020, South Sudan had recorded 1 317 confirmed cases of COVID-19,21 and this is expected to rise in line with continental and global trends. Thus, the government’s budget will be further strained by health spending to procure COVID-19 personal protective equipment, testing kits, quarantine facilities and equipment (such as ventilators and beds, infrared thermometers and medical aprons, among others). The RTGoNU has to address issues including the food security concerns of vulnerable communities, COVID-19 and access to basic social services such as health, water and sanitation by creating sustainable social safety nets and implementing economic reforms. Although several humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) operating in South Sudan will complement the government, the RTGoNU will still need to allocate sufficient funds towards progressively boosting food security and social protection.

Looking ahead, a critical task of the RTGoNU will be to steer economic development and reconstruction. Granted, the root causes of conflict in South Sudan include the struggle and contestation for political power, tribal animosity, proliferation of arms, perceptions of insecurity, issues of cattle-related conflict (cattle raids, counter-raids and fights over grazing land) and the breakdown of cultural values and norms. However, it is the lack of economic opportunities for the general population, the lack of economic development and poor social service delivery that have largely sustained political instability whilst creating the necessary conditions for the manipulation of local communities by factional leaders and militias to engage in conflicts.

South Sudan remains highly dependent on oil, and the majority of jobs are created in the oil sector and low productive and unpaid agriculture and pastoralist work.22 The dramatic fall in global oil prices due to COVID-19 will heavily affect South Sudan. A study by the Economic Commission for Africa has revealed that Africa’s oil-exporting countries’ export revenue may shrink by US$101 billion in 2020 due to COVID-1923 as a result of subdued global demand. This will definitely affect South Sudan, since the country’s crude oil accounts for more than 95% of exports24 and oil exports contribute over 40% to the national gross domestic product (GDP).25 The World Bank’s South Sudan Economic Update: Poverty and Vulnerability in a Fragile Environment report of 2020states that “four out of five South Sudanese live in absolute poverty and economic mismanagement and lack of prioritized investment in productive sectors of the economy has been suppressing economic growth”26. The RTGoNU has to fully implement the South Sudan National Development Strategy (June 2018–July 2021) and prudently utilise oil-sector revenue to diversify the economy. As recommended by the World Bank, the RTGoNU has to invest in efforts towards comprehensive macro-economic reforms, diversifying the economy, strengthening economic governance institutions, reducing inflation (which fell from 83.5% in 2018 to 24.5% in 2019), building social and economic multi-modal infrastructure, civil service reforms, transparent and accountable management of national resources, prioritising rural development and employment creation, and creating a conducive environment for foreign direct investment (FDI).27 Creating a conducive climate that attracts FDI will also entail undertaking policy, legal and regulatory reforms, since South Sudan is currently ranked 185 out of 190 countries on the 2020 World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index.28 All this will be complicated by the fact that South Sudan remains a fragile state with weak social and political cohesion, economic instability, compromised state legitimacy, poor social service delivery and demographic pressures. Currently, South Sudan is ranked third out of 178 countries in the world on the 2020 Fragile States Index,29 with Yemen and Somalia in the first and second positions respectively. Corruption may also affect the performance of the RTGoNU, with South Sudan currently ranked as the second-most corrupt country in the world, ranking 179 out of 180 countries (only surpassed by Somalia) on the Corruption Perceptions Index for 2019.30 The acknowledgement of these challenges will be a great stride in overcoming them in pursuit of the national development agenda for the RTGoNU.

Conclusion

The formation of the RTGoNU remains a golden opportunity to revive the South Sudan hope for peace, stability and prosperity. The main tasks and priorities of the RTGoNU should be to resolve outstanding issues that have delayed the formation of the unity government; bring an end to conflict; facilitate national healing and reconciliation; implement security sector reforms, economic development and stabilisation; and improve the lives and livelihoods of South Sudanese people. The RTGoNU will, however, be confronted with many political, economic and security challenges. All these challenges should be embraced as opportunities for implementing socio-economic and political reforms that have the potential not only to transform the lives of South Sudanese, but also to reposition the country’s strategic foreign relations with other members of the international community, especially foreign economic engagements. “Unity” is the hallmark of all governments of national unity. Therefore, nurturing cohesion, mutual trust, cooperation and genuine commitment to a shared national vision will be some of the essential factors for a successful RTGoNU in South Sudan.

Endnotes

- Africa Renewal (2019) ‘UN Chief Welcomes Decision to Delay Formation of South Sudan Unity Government’, 12 November, Available at: <https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/un-chief-welcomes-decision-delay-formation-south-sudan-unity-government> [Accessed 2 March 2020].

- Mohamed, Hamza (2019) ‘South Sudan: What’s Delaying the Unity Government?’, Al Jazeera, 12 November, Available at: <https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/2019/11/south-sudan-causing-delay-forming-unity-government-191110072933497.html> [Accessed 8 March 2020].

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) (2018) ‘Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS)’, 12 September, pp. 2–3, Available at: <https://igad.int/programs/115-south-sudan-office/1950-signed-revitalized-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-south-sudan> [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (2020a) ‘Report by H.E. Amb. Lt. Gen. Augostino Njoroge Interim Chairperson, RJMEC on the Status of Implementation of the R-ARCSS Submitted to the 71st Extraordinary Session of the IGAD Council of Ministers’, 23 April, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/jmec-statements/item/510-report-by-h-e-amb-lt-gen-augostino-s-k-njoroge-interim-chairperson-rjmec-on-the-status-of-implementation-of-the-revitalized-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-the-republic-of-south-sudan-submitted-to-the-71st-extraordinary-session-o> [Accessed 9 May 2020].

- Xinhua (2020) ‘South Sudan Opposition Leader Rejects President Kiir’s Allocation of States’, Xinhua, 8 May, Available at: <http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/africa/2020-05/08/c_139041211.htm> [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Ibid.

- Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (2020a) op. cit.

- United Nations News (2020) ‘UN Rights Chief Urges South Sudan Authorities to Address Inter-communal Violence’, 20 March, Available at: <https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1059822> [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- IGAD (2018) op. cit., p. 32.

- Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (2020b) ‘Report Summary: RJMEC Releases R-ARCSS Status of Implementation Report Covering 1st Quarter of 2020’, 20 April, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/media-center/news/item/508-report-summary-rjmec-releases-r-arcss-status-of-implementation-report-covering-1st-quarter-of-2020> [Accessed 5 May 2020].

- Ibid.

- Denis Louro, Oliver (2020) ‘Opposition and Government Forces Move to Training Site in Western Equatoria’, United Nations Mission in South Sudan, 3 February, Available at: <https://unmiss.unmissions.org/opposition-and-government-forces-move-training-site-western-equatoria> [Accessed 2 March 2020].

- Sudan Tribune (2019) ‘SPLA-IO Troops Arrive at Cantonment Site in Wau State’, The Sudan Tribune, 31 May, Available at: <https://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article67589> [Accessed 18 March 2020].

- Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (2020) op. cit.

- United Nations Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan (2020) ‘Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan’, Human Rights Council Forty-third Session 24 February–20 March, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/A/HRC/43/56> [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2020) ‘Refugees and Asylum-seekers from South Sudan – Total’, 30 April, Available at: <https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/southsudan?id=26> [Accessed 12 May 2020].

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2020) ‘South Sudan – Situation Report March 2020’, March, p. 1, Available at: <http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/emergencies/docs/FAOSituationReportSouthSudanMarch2020.pdf> [Accessed 12 May 2020].

- Ibid.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2020) ‘About OCHA South Sudan’, Available at: <https://www.unocha.org/south-sudan/about-ocha> [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) (2020) ‘Without Adequate Protection, Estimates Show that over 300,000 Africans could Lose their Lives due to COVID-19 – ECA Report’, 6 April, Available at: <https://www.uneca.org/stories/without-adequate-protection-estimates-show-over-300000-africans-could-lose-their-lives-due> [Accessed 2 May 2020].

- Africa Centre for Disease Control (CDC) (2020) ‘Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Latest Updates on the COVID-19 Crisis from Africa CDC’, 7 June, Available at: <https://africacdc.org/covid-19> [Accessed 7 June 2020].

- World Bank (2019) ‘South Sudan: Overview’, 16 October 2019, Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southsudan/overview> [Accessed 12 May 2020].

- United Nations ECA (2020) ‘ECA Estimates Billions Worth of Losses in Africa due to COVID-19 Impact’, 13 March, Available at: <https://www.uneca.org/stories/eca-estimates-billions-worth-losses-africa-due-covid-19-impact> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

- African Development Bank (2020) ‘South Sudan Economic Outlook’, Available at: <https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/east-africa/south-sudan/south-sudan-economic-outlook> [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- World Bank (2020a), op. cit.

- World Bank (2020b) ‘South Sudan Economic Update: Poverty and Vulnerability in a Fragile Environment (English)’, 1 February, Available at: <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/893571583937198098/pdf/South-Sudan-Economic-Update-Poverty-and-Vulnerability-in-a-Fragile-Environment.pdf> [Accessed 13 May 2020].

- Ibid.

- World Bank (2020c) ‘Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies’, p. 4, Available at: <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/688761571934946384/pdf/Doing-Business-2020-Comparing-Business-Regulation-in-190-Economies.pdf> [Accessed 6 June 2020].

- Fund For Peace (2020) ‘Fragile States Index Annual Report 2020’, Available at: <https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/> [Accessed 13 May 2020].

- Transparency International (2020) ‘Corruption Perceptions Index 2019’, p. 3, Available at: <https://www.transparency.org/files/content/pages/2019_CPI_Report_EN.pdf> [Accessed 13 May 2020].