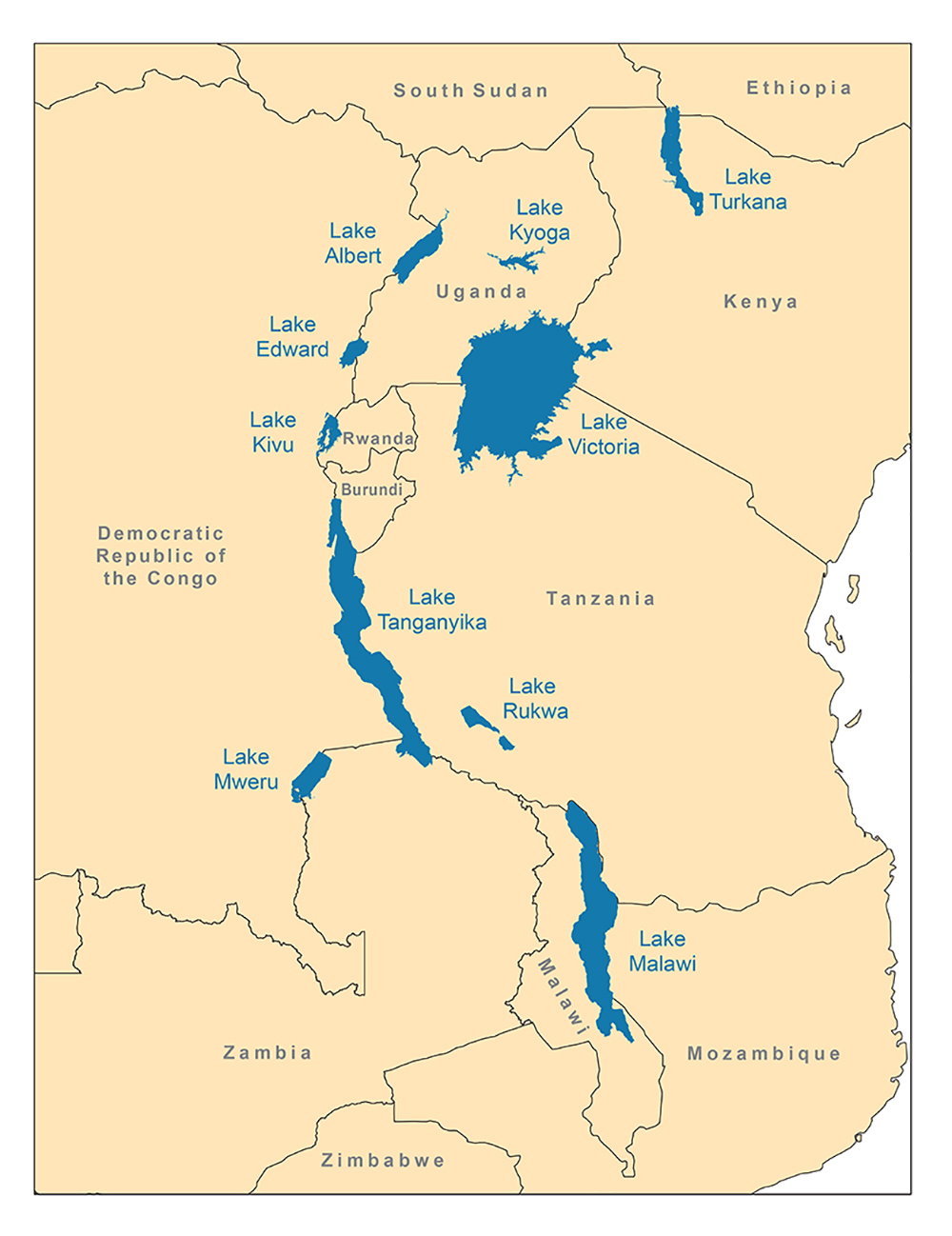

Peace, Security and Post-conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa is a bilingual compilation edited by two renowned professors of political science and history of African studies respectively. For decades, the Great Lakes region in Africa has witnessed wars and conflicts – most notably, genocide in Rwanda in 1994; liberation wars and conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), ending in 1997 and 2001 respectively; and post-electoral violence in the Central African Republic in 2016 (p. 1).

This book reveals the epistemological roots of conflicts and wars and their consequences on socio-economic and democratic landscapes, as well as peace modalities in the region. The 375-page book is a compendium of essays written by a host of scholars with vast knowledge and engagement on issues of conflict, peace and post-conflict reconstruction across the African Great Lakes countries. The book consists of 14 chapters, of which six are written in English and the remaining eight chapters are in French. This review was undertaken with the aid of a language translator.

In the first chapter (pp. 1–8), Bernard Mumpasi, Tukumbi Lumumba-Kasongo and Joseph Gahama provide background information on the series of conflict tragedies and wars that led to the breaking down of governance structures, and the economic and agricultural accomplishments of the 12 officially recognised countries of the Great Lakes region. Agentic efforts were analysed in lieu of reconstruction aimed at repositioning people, governments and society via dialogue and transformative projects. This chapter also offers introductory preambles to the other chapters in the book.

In the second chapter (pp. 9–28), Gahama attempts to historicise the evolution of conflicts and violence, specifically in Rwanda and the DRC. He extols the experiences of these countries vis-à-vis the inherent causes of conflict – which were predominantly due to political and ethnic disillusionments. It is maintained that the conflicts were characterised by the authoritarianism of the military juntas in the conflict environments of the region. In response to the conflicts, Gahama suggests preventive measures, leveraging upon democratisation and structural adjustment projects.

The third chapter is authored by Lumumba-Kasongo. He provides a theoretical explanatory tool for studying conflict that hinges on seven “mostly adopted” theories in social sciences (p. 34), with a view to simultaneously identifying and explaining the causes, trajectories and manifestations of conflicts, as well as their socio-economic implications on different societal strata. Notably, the general discourse remains comprehensive for students of conflict analysis.

Patricia Gaboua, in the fourth chapter (pp. 49–82), analyses the strategies for economic diversification in the Great Lakes countries. These strategies are tagged as factors of stability and development, with examples in Burundi, Republic of Congo and the DRC. She maintains that diversification and interdependence trades have the economic propensity to establish positive correlation between sociopolitical stability and development prospects in the region.

Chapter five (pp. 83–106) was contributed by Peter Wekesa, who uses a comparative lens to view land resources, livelihoods and ethnic mobilisation in Bunyoro, Uganda and Turkana, Kenya. This comparative approach allows for dynamic analysis of the recent oil discoveries in the two sampled localities. The author affirms that ethnic mobilisation stands at the centre of people’s resilience, the stability of the state and issues of legitimacy, among other dynamics in the region.

Jean-Marie Katubadi-Bakenge, in chapter six (pp. 107–156), concentrates on the theoretical analysis of the economic community in Burundi and the DRC. He carefully considers the study of public space, led by Jürgen Habermas and the Foucauldian analysis of government. On these themes, Katubadi-Bakenge stresses that socio-economic and demographic enquiries should be made on what seems problematic within the economic communities of the region.

In chapter seven (pp. 157–184), John Baligira examines land policy and conflicts in Uganda, using the example of Kibaale District. This chapter is methodologically clear in its sampling procedure and research instrument. The author analyses the interactions among parties claiming land rights. He submits that fragmentations of land conflicts were largely being influenced by politics in Uganda.

Earlier in the book, Gaboua emphasises interdependence trades as a factor for economic stability and development. As a follow-up to this, chapter eight (pp. 185–208), written by François-Xavier Mureha and Idrissa Ouedraogo, investigates the reciprocal impact of interdependence trades on civil conflicts in the Great Lakes region. This was conducted via symbiotic inquiry of the two variables, namely interdependence trades and civil conflicts. The authors maintain that there is a significant cause–effect relationship between the interlinked variables.

In chapter nine (pp. 209–236), William Tayeebwa contributes to a shift from a conventional model of journalism to the new frameworks in peace journalism, using the examples of Burundi and Uganda. His shift in analysis is based on proposals from peace journalism specialists, which sought to deconstruct conventional journalism that favours conflict reportage, and promote new frames for communal harmony (p. 209). The author’s writing reveals, on the one hand, that the conventional model appears satisfactory to media outfits because violent stories sell fast but are detrimental to human peace. On the other hand, there is a dearth of well-formulated frameworks in new peace journalism for peace enhancement.

In chapter 10 (pp. 237–270), Félicien Mbambu affirms the threats of armed conflicts in the DRC and other countries in the Great Lakes region. The proliferation of militias has strengthened these armed conflicts, as is evident across the forest areas in the region. The author argues that understanding conflict dynamics is an inclusive action for the environmental management of forest areas and climate change in the region.

David-Ngendo Tshimba, in chapter 11 (pp. 271–298), discusses how peace can be endangered by community narratives of precedent massacres, as related to two conflicting clans in Mucwini, Kitgum District of northern Uganda. Ethnological inquiry was conducted with a view to identifying how best to resolve past wrongs from the perspectives of the perpetrators and victims of massacres. Tshimba suggests restorative justice as a means to engendering peace and harmonious co-habitation in post-massacre communities.

Chapter 12 (pp. 299–326), written by Célestin Tukala, underscores the privatisation of security in the Great Lakes region. This is illustrated through two cities in the DRC, Goma and Kinshasa. Security privatisation is considered problematic due to identifiable weak state structures.

Jean Liyongo-Empengele, in chapter 13 (pp. 327–358), evaluates the effect of radio programmes in relation to the promotion of culture and peace in Burundi and the DRC. The methodology used was survey research, conducted in selected regions of the two countries. It was clearly stated that community radio has a notable influence in the promotion of peace in the study areas.

Conclusively, in the last chapter (pp. 359–366), the editors maintain that there are hard-won achievements in governance and economic prospects in the region. However, they posit that “the situation in the Great Lakes region is still worrisome” (p. 359). They therefore conclude by charting ways for sustainable peace, security and reconstruction across countries in the region. They recommend the re-enforcement of African peacebuilding capacities, integrative economic purposes, strong interdependence in key service areas, the principles and values of good governance, the establishment of welfarist political regimes and the introduction of peace education across systems.

Overall, Peace, Security and Post-conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa deepens the discourse of post-conflict reconstruction in the Great Lakes region. It provides in-depth historical analysis and theoretical dispositions with comparative inclusions, and addresses issues more comprehensively that have only been tangentially explored in different articles. However, there are a few discussions manifestly absent from the book. These include the role of gender-based institutions in post-conflict reconstruction processes; the hybrid engagement of local, state and non-state institutions; and advanced comparative lessons from other regions on the African continent. Another limitation is that the citation format is not uniform in the book. It is clear that the majority of chapters combined endnotes and references, but this was not consistent throughout. In addition, an appendix should have been created for the abbreviations used in the book.

Notwithstanding these minor challenges, Peace, Security and Post-conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa is an insightful book and a great resource. It is of significant relevance to research in peace and conflict studies, as well as policy framing in post-conflict reconstruction. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to interested scholars in the study of peacebuilding in post-conflict countries in Africa and beyond. It would also be useful to students of history, policy analysis, international studies, governance and development studies, social work, and peace and strategic studies at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, as well as media practitioners, security officials and other practitioners in related fields.