Introduction

The activities of violent extremist and terrorist groups in West Africa have been on the rise since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since January 2021, high-profile attacks by groups affiliated with the Islamic State (ISIS) and Al-Qaeda have been recorded in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Although the Sahel region of West Africa is currently the epicentre of violent extremism and terrorism (VET), the threat is gradually spilling over into the littoral States along the Gulf of Guinea (GoG).[1] Several coastal States along the GoG have recently either witnessed attacks or identified the presence of terrorist groups in parts of their territory.[2]Ghana provides a clear example of the contagion effects of VET in the coastal States, although the countryhas not witnessed any direct terrorist attacks. In July 2021, the Minister of Information, Kojo Oppong Nkrumah, affirmed this and noted that ‘terrorist groups operating in West Africa have managed to recruit some Ghanaians to aid their cause.’[3] Unlike its neighbouring countries, like Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire that are experiencing terrorist attacks, Ghana has managed so far to prevent attacks despite its vulnerabilities. This raises critical questions about Ghana’s seeming resilience against the risk of VET and how it is responding to the scourge. This article probes these questions by examining the factors that render Ghana vulnerable to, and at the same time resilient to, VET. It also assesses Ghana’s response to the threat and concludes with some policy recommendations.

Ghana’s Vulnerability to Violent Extremism and Terrorism

The factors that make Ghana vulnerable to terrorist attacks are complex and wide-ranging. However, for the purpose of this discussion, six factors are briefly explained.

Proximity to Countries Affected by Violent Extremism and Terrorism

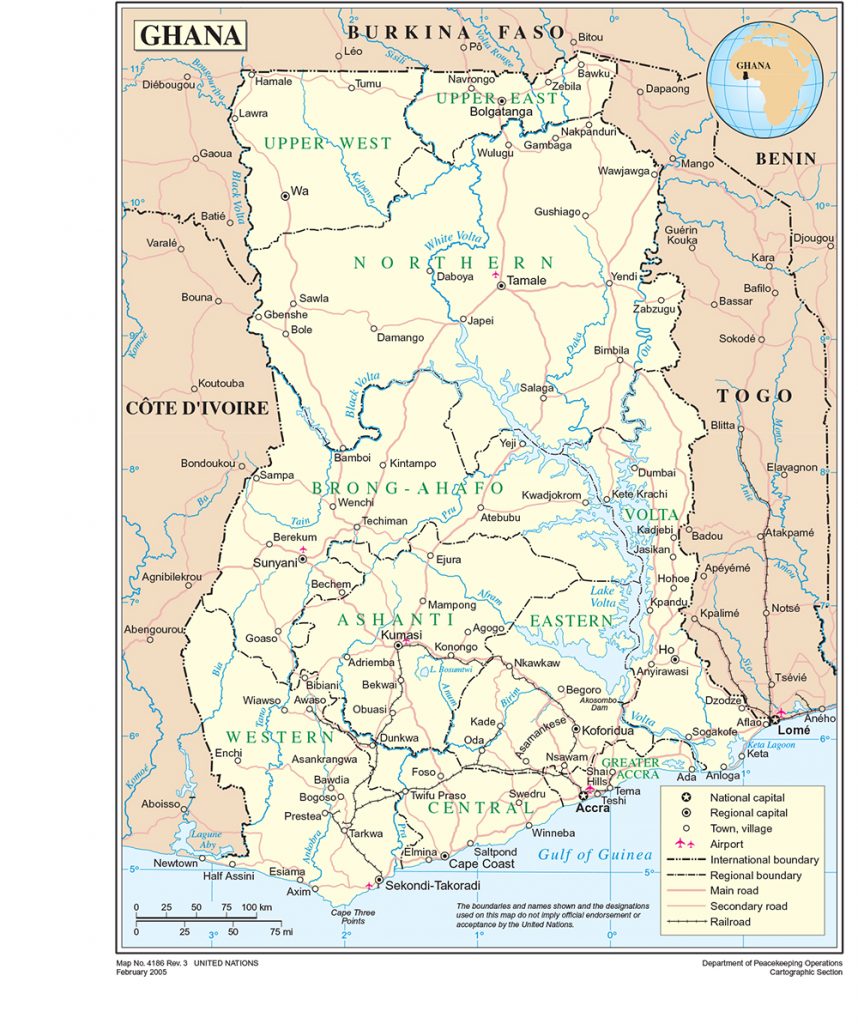

The first obvious factor is Ghana’s proximity to countries where groups such as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam waal Muslimeen (JNIM), and Ansarul Islam operate. Burkina Faso, for instance, is a strategic location for terrorist groups because it is situated at the junction of the Sahel and the GoG, sharing borders with Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Togo. The strong historical, cultural, trading, and political links between Burkina Faso and these coastal countries make each of them vulnerable to terrorist attacks. The 2016 Grand-Bassam attack in Côte d’Ivoire by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is an example of how violent extremist groups could strike a coastal State beyond their haven in the Sahel. The leaders of JNIM (Iyad Ag Ghali, Djamel Okacha, and Amadou Koufa) have on countless occasions called on militants and Fulani people in West Africa to mobilise for the Jihadist cause not only in Mali, but also in Burkina Faso, Niger, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Ghana, Senegal, Nigeria, and Cameroon.[4] In line with this grand agenda, many Salafi-Jihadist groups have migrated southwards, exploiting the fragility of some coastal States. For example, extremist elements have been reported in north Benin, Togo, and Ghana following the Otapuanu Military Operation[5] in south-eastern Burkina Faso in March 2019.[6]

The Threat of Home-grown Terrorism

The second factor is the threat of home-grown terrorism by Ghanaian foreign terrorist fighters who have or will in future return home.[7] The recruitment of Ghanaians by ISIS through social media propaganda and violent extremist groups operating in Burkina Faso is not a secret. In 2015, a 25-year-old Ghanaian university graduate, Mohammad Nazir Nortei Alema, was recruited by ISIS but later died in Syria.[8] In October 2017, there were reports that about 100 Ghanaian migrants joined ISIS in Libya, with some forcefully conscripted and others joining voluntarily for financial rewards and safety.[9] Anecdotal reports suggest that most of the surviving Ghanaian foreign terrorist fighters are returning home. The risk of home-grown terrorism is currently low. However, the danger is that ISIS can direct some of these Ghanaian returnees to carry out attacks in Ghana when they face difficulty gaining access. Furthermore, ISIS can use them and their local agents to create terrorist cells, recruit more people, and launch surprise attacks in the future.

Growing Influx of Irregular and Labour Migrants

The third factor is the growing influx of irregular and labour migrants into the country from Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and the Middle East. The presence of Burkinabe migrant labourers in the Upper West Region of Ghana has, for instance, exacerbated chieftaincy and intercommunal violence related to land access and the migration of farmers and herders. Communities such as the Doba and Kandega, Kologo and Navrongo, and Bavungnia and Wusungu along the borders with Burkina Faso have all experienced disputes. Due to the tribal links between the border communities, local conflicts in Ghana have often affected neighbouring communities in Burkina Faso. The concern is that JNIM, ISGS, and their affiliates can exploit these localised conflicts by either supporting and aligning themselves with marginalised communities or manipulating identity affiliations to develop support.

Participation of Suspected Terrorists in Artisanal Gold Mining

Reports suggest that suspected terrorists participate in artisanal gold mining in the northern part of the country. Examples of where this occurs are in the forest between Wuru in the Sissala East District of Ghana and across the border in Kunu in Burkina Faso. The presence of migrant labourers has sometimes caused renewed intercommunal tensions due to the racist rhetoric against Burkinabe and other Sahelian migrants. While the mining sector in Burkina Faso and other parts of the Sahel has been targeted by JNIM and ISGS for revenue mobilisation and recruitment, the link between artisanal gold mining in Ghana and terrorism is weak. Nonetheless, mining communities in the border regions where the State lacks authority could become a source for terrorist recruitment due to local grievances over government’s offensive operations against illegal miners, known locally as galamsey, which has left many young people unemployed. Drawing from the experiences in the Sahel region, the increased local awareness of resource predation by local and foreign mining companies as the economic gap widens could serve as an entry point for violent extremist groups to manipulate local grievances by encouraging those affected to attack the symbols of exploitation.

Multi-layered Issues

The fifth factor which lies at the core of VET in West Africa is the multi-layered issues of unresolved localised conflicts, poverty, unemployment, injustice, political and social marginalisation, poor governance, lack of the rule-of-law, weak border controls, and limited State presence in peripheral communities. Others include weak State institutions, endemic corruption, arms proliferation, and transnational organised crime, such as drug trafficking, kidnapping for ransom, and maritime piracy. At present, there are some unresolved intercommunal conflicts in communities such as Saboba and Chereponi, the Kussasi-Mamprusi ethnic violence in Bawku, the separatist rebellion in the Volta region, and the farmer-herder conflicts. There are concerns that the Zongocommunities (settlements of Hausa -speaking traders) could devolve into hotbeds of radicalisation and VET due to their intrinsic ties to Islam in the Sahel, their perceived marginalisation, poverty, and high unemployment. Hausa is also a language they have in common with Sahel-based jihadist groups. Due to their predominant immigrant status and insufficient integration into Ghanaian society, there are concerns that these communities could serve as entry points for more extremist Muslim rhetoric and anti-State sentiment. Most often, violent extremist groups take advantage of the structural vulnerabilities and public discontent to present themselves as an alternative to the State by providing humanitarian services and socioeconomic interventions, such as providing boreholes, food and jobs, and building schools and clinics in remote areas. By doing so, they can gain local support, and communities often accept them as a means of survival, even when their ideology is not approved of.

Ignorance and Limited Public Awareness

VET thrives on ignorance and a lack of awareness among the population. In Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, Jihadist groups exploit the ignorance of the populace and use subtle strategies to recruit people, radicalise them, and then carry out attacks. In Ghana, public knowledge about the causes, recruitment strategies and implications of terrorism is very low. A research report on the ‘Risk or Threat Analysis of Violent Extremism in Ten Border Regions of Ghana’ published by the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) in June 2021 revealed a lack of citizen understanding and appreciation of risk factors underpinning violent extremism.[10] This poses a danger to the country.

Ghana’s Resilience to Violent Extremism and Terrorism

Despite its vulnerabilities, Ghana has so far warded off terrorist attacks. The 2021 Global Peace Index Report, therefore, ranked Ghana as the second-most peaceful country in Africa.[11] In this article, it is argued that Ghana’s resilience to VET can be attributed to the country’s democratic and good governance credentials, robust security sector with several years of international peacekeeping experience, vibrant media, active civil society, strong traditional system, religious and ethnic tolerance, and general culture of peace among Ghanaians. Four of these factors are examined further.

Interfaith Tolerance and Cooperation

Ghana has an enviable tradition of interfaith tolerance and cooperation, especially between Christians and Muslims. Admittedly, while sentiments of religious discrimination against Muslims in Christian missionary schools exist, it has rarely translated into actual interfaith conflict. Christians and Muslims host their counterparts for major festivals like Easter, Christmas, and Eid al-Adha. In 2019, for instance, the National Chief Imam, Sheikh Osman Sharubutu, attended the Christ the King Catholic Church in Accra for Easter service as part of his 100-year birthday celebrations.[12] Moreover, churches and mosques offer social services to people of all faiths. The ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) has adhered to a tradition of having a Muslim running-mate alongside a Christian presidential candidate for over two decades. All these actions have promoted peaceful coexistence and religious harmony, despite the sentiments of some minority religious groups.

The Ghana National Peace Council (NPC) is the embodiment of the religious harmony in the country. The NPC, which facilitates and develops mechanisms for conflict prevention, management, and resolution to build sustainable peace, has a membership that cuts across the key religions in the country – Tijahaniya Muslims,Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission, Al-hasuna Muslims, Ghana Christian Council, Catholic Bishops Conference, Ghana Pentecostal Council, Ghana Charismatic Council, and the African traditional religion. Through mediation and dialogue, advocacy, networking, and peace education, the NPC has promoted peaceful coexistence among Ghanaians and resolved conflicts with the potential to plunge the country into civil war. For example, NPC interventions helped reduce tensions and violence during the contested presidential elections in 2012 and 2020.

Ethnic Tolerance and a Culture of Peace

Ghana is a heterogeneous society with diverse ethnicities that include the Akan, Ewe, Ga- Adangbe, Mole-Dagbani, Guan, and Gurma. Although there are some intra- and inter-ethnic disputes, the tensions have rarely caused major national political or social problems. The multi-ethnic composition of society and a general culture of peace has been a key determinant of harmony and national cohesion due to the consciousness of ‘one nation, one people, and one common destiny’ among Ghanaians. Thus, most Ghanaians generally express tolerance for people of different ethnicities. There is intermarriage among different ethnic groups, and as the 2015 Afrobarometer report rightly points out, ‘in each of the country’s regions, one can identify residents of different religious and ethnic backgrounds, and in some cases, small ethnic groups have their own traditional heads who are well-recognized by the traditional leaders in the host regions.’[13] The implication of this level of tolerance is that it has made it difficult for violent extremists who fan ethnic and religious intolerance to pursue their agenda.

Active Civil Society

Ghana has an active civil society with thousands of registered civil society organisations (CSOs) operating in many sectors, including the security, humanitarian, peacebuilding, governance, development, education, and health sectors. CSOs largely operate in a free and open civic space and do not suffer from persistent State interference or harassment. The likes of the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), Centre for Democratic Development (CDD), and Institute for Democratic Governance (IDEG) are worth mentioning. Most of these CSOs work on programmes that promote peaceful and inclusive societies and mitigate structural conditions conducive to the spread of VET through peacebuilding, early warning and response, good governance and human rights, addressing gender issues, interfaith dialogue, and youth engagement. Some CSOs like WANEP work with marginalised groups in periphery areas to promote political participation and provide outlets for addressing community grievances. Through service delivery, advocacy, and watchdog roles, CSOs have contributed to deepening Ghana’s democracy, government effectiveness and accountability. The active role of CSOs has generally helped to safeguard peace in the country.

Vibrant Media

Ghana’s public and private media (both conventional and new media) has been a critical pillar in the democratisation and governance processes. It has continually set the agenda on critical governance and development matters, sustained the discourse with the active participation of citizens, and brought pressure to bear on government to effect change and act on critical national issues. The Ghanaian media has been a custodian of the freedom of speech, the right to information, and the representation of different opinions in political discourse. While admitting that some media houses have been politicised and irresponsible in their reportage, they have largely not been used as a tool to spread hate speech and incite hatred and violenceagainst ethnic or religious groups. The vibrancy of the media has been possible due to constitutional provisions in the 1992 Constitution of Ghana ensuring a free and independent press, including laws against censorship, government interference, and harassment.

Ghana’s Response to Violent Extremism and Terrorism

Ghana’s response to VET can be categorised according to legal, operational, and multilateral responses.

Legal Response

Ghana has adopted several legal frameworks in line with regional and international conventions and protocols. Key among these are the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2008 (Act 762), the 2014 amendment to the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2008 (Act 749), and the Organized Crime Act of 2010. These Acts include provisions against the financing, recruitment, and support of terrorist activities. To complement these Acts, the government adopted the National Framework for the Prevention and Countering of Violent Extremism and Terrorism (NAFPCVET) in 2019. The NAFPCVET aims at preventing terrorism and minimising the threat to Ghana and its interests. It operates through four mutually reinforcing pillars, namely:

- Prevention measures to counter violent extremist and terrorist attacks by addressing the root causes, minimising vulnerability, and building resilience.

- Pre-empting activities to detect and deter violent extremist and terrorist threats.

- Protection measures to safeguard vulnerable infrastructure and spaces.

- Response activities to mitigate the impact and recover from violent extremist activities and terrorist incidents.

The operationalisation of the NAFPCVET has resulted in coordination across ministries, departments, and agencies to prevent VET.

Operational Response

At the operational level, the Ministry of National Security, Ghana Police Service, Ghana Armed Forces, and other allied security agencies have conducted several capacity-building programmes and counterterrorism simulation exercises to test their preparedness in the event of any terrorist attacks. Additionally, the government has occasionally deployed ‘Operation Conquered Fist’, a counterterrorism operation, to the border areas to combat transnational crimes and deter possible terrorist attacks. This operation has contributed to maintaining a resolute, robust front that has arguably deterred potential attacks. Nonetheless, Ghana’s response has so far been overly security-oriented. Socioeconomic and political measures to address the root causes of VET have been insufficient. CSOs, media and citizen participation in the implementation of government’s counterterrorism initiatives are also limited. Overall, this has affected local ownership and citizen engagement in the NAFPCVET implementation.

Multilateral Response through the Accra Initiative

Ghana is a leading member of the Accra Initiative which was launched in 2017 as a multilateral cooperative and collaborative security mechanism. The Accra Initiative, which includes Ghana, Burkina Faso, Togo, Benin, and Cote D’Ivoire, with Mali and Niger as observers, seeks to prevent the spillover of terrorism from the Sahel and to address transnational organised crime and violent extremism in the border areas. It operates with a central coordinator and permanent secretariat in Ghana’s national security secretariat, and focal points in each member country. Since its establishment, the Accra Initiative has facilitated periodic meetings of ministers in charge of security, heads of security and intelligence agencies, as well as information and intelligence sharing on VET and transnational organised crime among member countries.[14]

There has been a series of cross-border security operations among Member States as well. In May 2018, Operation Koudanlgou I was jointly conducted by Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Togo in their border areas. Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana also conducted Operation Koudanlgou II in November 2018. A year later, Togo and Ghana jointly conducted Operation Koudanlgou III. These operations have led to the arrest of suspected militants and temporarily halted terror groups’ activities and movements. But it has been ad hoc, limited in duration (usually four to five days’ deployment) and geographic reach. Moreover, the language barrier between English-speaking Ghana and its Francophone counterparts has occasionally hindered effective communication. The Accra Initiative is also predominantly military-oriented with limited attention to socioeconomic, political and governance challenges.[15]

Conclusion and Recommendations

Ghana has managed to maintain its long history of peace and stability in a generally turbulent region characterised by political crises, armed conflicts, and VET. Apart from the lessons that Ghana’s experience presents to other countries in the region, it demonstrates how proactive responses could deter potential terrorist attacks, at least in the short to medium term. Nonetheless, the activities of violent extremist groups in Ghana’s immediate neighbouring countries serve as a continued reminder of the potential threat terrorism poses to the country. To strengthen the country’s resilience against the threat, the following recommendations are made:

- The government should adopt a balanced approach, combining both military and non-military interventions and addressing the socioeconomic, political and governance challenges at the root of VET.

- Citizens, communities, civil society, the media, and religious and traditional authorities should be actively engaged in the implementation of the NAFPCVET through a whole-society approach to promote local ownership and participation.

- Increase education and awareness of the causes, motivations, modus operandi, and implications of VET to individuals and communities to safeguard and protect the unity of the State.

- Enhance tracking and intelligence-gathering on Ghanaian foreign terrorists to prevent the growth of home-grown terrorism.

In conclusion, Ghana cannot be complacent with its relative stability. The durability and risk of VET in West African coastal States call for increased local resilience and enduring national responses.

Dr Festus Kofi Aubyn is the Regional Coordinator of Research and Capacity Building at the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP) regional office in Ghana. He previously worked with the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) in Ghana as a Senior Research Fellow.

Endnotes

[1] Théroux-Bénoni, Lori-Anne and Adam, Nadia (2019) ‘Hard Counterterrorism Lessons from the Sahel for West Africa’s Coastal States’, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/hard-counter-terrorism-lessons-from-the-sahel-for-west-africas-coastal-states [Accessed 29 July 2021].

[2] UNDOC (2021) ‘UNODC Holds a National Consultative Meeting with Counter-terrorism Focal Points of Ghana’, Available at: https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/2020-09-28-ghana-counter-terrorism.html [Accessed 27 July 2021].

[3] Asaase Radio (2021) ‘Terrorist Groups are Recruiting in Ghana, says Oppong Nkrumah’, Available at: https://asaaseradio.com/security/terrorist-groups-are-recruiting [Accessed 29 July 2021].

[4] International Crisis Group (2019) ‘The Risk of Jihadist Contagion in West Africa’, Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 149.

[5] Operation Otapuanu or ‘Rain of Fire or Lightning’ in Gulmacema is a counterterrorism operation.

[6] Jeuneafrique (2019) ‘Des Jihadistes Présents au Bénin, au Togo et au Ghana, Selon les Services Burkinabè’ [‘Jihadists Present in Benin, Togo and Ghana, According to Burkinabe Services’], Available at: https://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/762638/politique/burkina-des-jihadistes-de-lest-se-seraient-refugies-au-benin-au-togo-et-au-ghana [Accessed 28 July 2021].

[7] Zulkarnain, Mohammed (2020) ‘Nature of Home-Grown Terrorism Threat in Ghana’, Journal of Terrorism Studies, 2 (2).

[8] BBC (2015) ‘Ghanaian Man “Joins Islamic State” Militants’, Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-34056871 [Accessed 26 July 2021].

[9] Ghanaweb (2017) ‘100 Ghanaians Join ISIS – Minority’, Available at: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/100-Ghanaians-join-ISIS-Minority-589477 [Accessed 30 July 2021].

[10] NCCE (2021) ‘Risk or Threat Analysis of Violent Extremism in Ten Border Regions of Ghana’, Available at: https://www.nccegh.org/publications/view/62-risk+threat+analysis+of+violent+extremism+in+ten+border+regions+of+ghana.pdf[Accessed 18 October 2021].

[11] Institute for Economics and Peace (2021) ‘Global Peace Index 2021: Measuring Peace in a Complex World’, Available at: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GPI-2021-web-1.pdf [Accessed 10 October 2021].

[12] Nunoo, Favour (2019) ‘Ghana’s 100-year-old Imam Who Went to Church’, Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48221879 [Accessed 1 August 2021].

[13] Armah-Attoh, Daniel and Debrah, Isaac (2015) ‘Day of Tolerance: “Neighbourliness” a Strength of Ghana’s Diverse Society’,Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 58.

[14] European Council on Foreign Relations (2020) ‘Mapping African Regional Cooperation’, Available at: https://ecfr.eu/special/african-cooperation/accra-initiative [Accessed 2 August 2021].

[15] Kwarkye, Sampson; Abatan, Ella Jeannine; and Matongbada, Michaël (2019) ‘Can the Accra Initiative Prevent Terrorism in West African Coastal States?’, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/can-the-accra-initiative-prevent-terrorism-in-west-african-coastal-states [Accessed 2 August 2021].