The Western Sahara conflict has been described as a ‘frozen conflict’ and as ‘decolonisation’s last stand.’ Despite the multiple ceasefires throughout its history, the conflict has not been fully resolved. Since 1974, Western Sahara has been on the shortlist of non-self-governing territories. However, it is the only one on the list that has not condoned this status. The Polisario Front spent 50 years fighting for the independence of the Sahrawi Arab Republic from Morocco, mostly using arms and guerrilla warfare. This period of violence was followed by a ceasefire between the two stakeholders. Nonetheless, in 2020, Morocco’s response to the Sahrawi protests resulted in a resumption of fighting by the Polisario Front, essentially reopening ‘Pandora’s Box’ and showing that, despite the ceasefire, a permanent solution is urgently needed. This would need to happen within the broader African security landscape, which is currently experiencing a shift amidst the weakening of United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations, the growing presence of various private military companies (PMC), and the emerging role of countries such as Russia and Türkiye in African conflict situations. Considering the aforementioned changes, this article seeks to assess whether these shifts in the African security landscape will influence the situation in Western Sahara by maintaining the status quo or revitalising the efforts to resolve or exacerbate the existing tensions.

Background

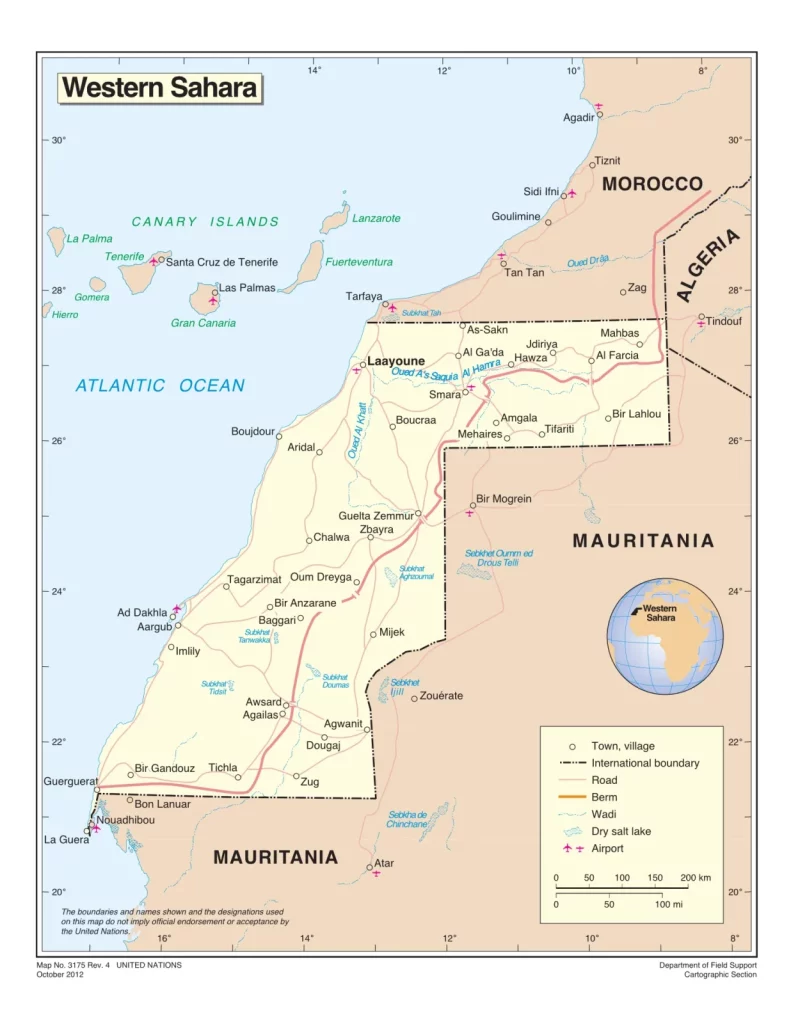

Western Sahara, a region with people mainly of Arabic origin and related to those of Mauritania and Morocco, was occupied during the colonial era by Spain. The Spanish era lasted from 1884 to 1974, after which Western Sahara was incorporated into Spanish Morocco.1Shelley, T. (2004) Endgame in the Western Sahara: What future for Africa’s last colony, London: Zed Books. As the wave of decolonisation spread across Africa, Sahrawi students in Morocco started organising and agitating for the independence of Western Sahara. However, in 1975, following the Green March of Moroccan civilians, both Mauritanian and Moroccan troops entered Western Sahara to annex parts of the territory.2Weiner, J.B. (1979) ‘The green march in historical perspective’, Middle East Journal, 33(1), 20–33. This was met with dissatisfaction from the Polisario Front, the pro-independence group formed by Sahrawi students in Morocco. The Polisario Front thus embarked on a campaign of guerrilla warfare, which was backed by Algeria and eventually led to the withdrawal of Mauritania from the region in 1979.3Besenyő, J.; Huddleston, R.J.; and Zoubir, Y.H. (Eds) (2022) Conflict and Peace in Western Sahara: The Role of the UN’s Peacekeeping Mission (MINURSO), London: Taylor & Francis. Morocco, however, remained and hostilities continued until 1990 when, under the auspices of the UN, a settlement plan was initiated and a peacekeeping mission, namely the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), was established. The ultimate aim was to hold a referendum on independence for the Sahrawi people. The referendum was originally scheduled to take place in 1992, but is yet to come to fruition. Instead, the region has seen interspersed periods of turbulent warfare and ceasefires.

In the meantime, the main responses from the international community in pursuit of a permanent resolution to the dispute came from the level of the UN, specifically in the form of the Baker plans. The Baker I Plan was introduced by special envoy James Baker in 2000 and offered an option for Western Sahara to be an autonomous state within the Moroccan jurisdiction. The Sahrawi government would have control over all of its policies, except for defence and foreign policy. It was accepted by Morocco but rejected by the Polisario Front. In continuation of these efforts, in 2003, the Baker II Plan was proposed by the United States of America (USA) for a fully self-governing Western Sahara. Morocco clearly rejected this proposal, while the Polisario Front ostensibly accepted it as a basis for negotiations. The next round of discussions occurred in 2007 and 2008 in New York during the Manhasset negotiations. The result was a stalemate, with Morocco advocating for autonomy and Western Sahara favouring full independence.

Regional and international responses

The key regional factor that contributes to the continued resistance of the Polisario Front to full annexation by Morocco is the support of Algeria. The Algerian town of Tindouf was the birthplace of the Polisario Front and where the declaration of the Sahrawi Arab Republic took place in 1976.4Guindo, M.G. and Bueno, A. (2017) ‘The Role of Sahrawis and the Polisario Front in Maghreb-Sahel Regional Security’, In Ojeda-Garcia, R.; Fernández-Molina, I.; and Veguilla, V. (Eds), Global, Regional and Local Dimensions of Western Sahara’s Protracted Decolonization: When a Conflict Gets Old, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 165–186. Ever since, Algeria has rejected territorial claims by Morocco over Western Sahara and, as a result, broke diplomatic ties with Rabat. In addition, Algeria supported the Polisario Front militarily during the 1980s and 1990s by providing tanks and arms.5Ramadhini, M. (2014) ‘The Continuous Support Of Algeria Towards Western Sahara’s Self-Determination Proposal (2007-2014)’, Bachelor’s thesis, Fisip UIN Jakarta. It should be noted, however, that the official stance from Algiers is that it currently does not provide military support to any Sahrawi entity.

Reflecting on this situation, it can be understood that Algeria’s role has been critical in this conflict. On the one hand, the positive side to Algeria’s involvement is that it provides a haven for a group that is demanding territorial sovereignty, which no other state actor or international institution has done. On the other hand, the negative impact is that its support to the Polisario Front fuels the existing conflict, rather than helping to find a peaceful resolution.

Regarding the international community, as mentioned, the UN has proposed the referendum on independence as a potential solution, without any success in this regard.6Diallo, G. (1993) Mauritania – the other apartheid? Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. The convening of the two sides at the negotiating table and agreeing to a ceasefire in 1991 has been the only successful intervention by the UN, with only statements of hope for a successful negotiation from UN envoys coming in the succeeding years.

Other international actors whose involvement has been crucial are Spain and the USA. Spain has pursued actions against the demands of the Polisario Front. In 1975, it facilitated the Madrid Accords, which divided Western Sahara between Morocco and Mauritania.7Khakee, A. (2014) ‘The MINURSO mandate, human rights and the autonomy solution for Western Sahara’, Mediterranean Politics, 19(3), 456–462. Since then, Spain has remained mostly idle in this conflict. This changed in 2020, when Madrid followed Washington’s stance after the signing of the Abraham Accords with Morocco. The Abraham Accords saw the USA formally recognise Western Sahara as part of Morocco, with Spain following suit. This type of involvement chiefly serves to increase tensions, as such a stance in favour of one party alienates the other and causes them to seek more forceful solutions.8Naylor, P.C. (1987) ‘Spain and France and the Decolonization of Western Sahara: Parity and Paradox, 1975-87’, Africa Today, 34(3), 7–16.

Changes in the landscape

The evolution of PMCs, the cases of Russia and Türkiye, and regional military cooperation

The past decade has seen a shift from state military personnel to the deployment of private and contracted personnel in the form of PMCs. Out of these, one group has drawn particular attention: the Russian Wagner Group, previously led by the late Yevgeniy Prigozhin. Its presence has been notable in countries such as Niger, Mali, and Sudan, as well as in the provision of contracted personnel in countries such as the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Chad and Guinea, among others.9Dworkin, A. (2022) ‘North African standoff: How the Western Sahara conflict is fuelling new tensions between Morocco and Algeria. European Council on Foreign Relations’, Available at: https://ecfr.eu/publication/north-african-standoff-how-the-western-sahara-conflict-is-fuelling-new-tensions-between-morocco-and-algeria/#_ftn1 [Date accessed: 8 February 2024]. This alone is not a great change, but combined with the weakening presence of UN and European forces in Africa, it can be considered massive. In the past two years, European Union (EU) Member States such as France have withdrawn their armed forces from Niger, Mali, Mauritania and Burkina Faso. At the same time, the UN stabilisation missions in DRC, CAR, and Mali are facing opposition from local communities and the government. In addition, several challenges have been reported with financing the UN peacekeeping forces and their sustainability. While European countries are gradually reducing their support, there have also been statements by former USA President Donald Trump who, if elected again, said he would cut substantial funds earmarked for the UN, suggesting funding for the UN in Africa may be bleak.10Fasanotti, F.S. (2022) ‘Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, commercial concessions, rights violations, and counterinsurgency failure’, Brookings report, 8 February. Another change is the introduction of new military players in the region. Such examples include Türkiye, which, having seen development in its military industry capacity, is exercising hard power diplomacy across the globe. Finally, it is important to note that international players are not the only ones involved in Africa’s security landscape. Examples from African nations, such as the involvement of Rwanda in a regional conflict in the Great Lakes, are expected to continue emerging.

The new security landscape unfolding in Africa differs considerably from the one with which the frozen conflict initially started. The involvement of new state actors and the introduction of contracted personnel to support the governments in many countries has brought changes in the Sahel, East Africa, and the Horn of Africa. As part of this, there are many considerations about whether the Western Sahara will be affected and if there will be a change to the current status, either for the benefit or disadvantage of the Sahrawi people. In order to have a better understanding, it is important to examine the trajectory of each newly introduced actor, especially with regards to Western Sahara.

Russia

Russia, as mentioned, has been the main actor in the private military personnel trend in Africa. Its presence in West Africa is substantial, showing the interests of Moscow in engaging in the region for reasons beyond purely military ones. The Kremlin sees the resource-rich region of Africa as a place to continue exerting influence in the global metal and mineral markets. In Guinea, extraction of copper is taking place by Russian firms, whereas the coup in Niger is bringing the gold mining industry closer to companies with Russian interests. Western Sahara is resource-rich, as it has deposits of iron, gold, uranium, petrol, gas and phosphate, making it an increasingly attractive partner for Russia. However, the involvement of Moscow in Western Sahara has been an exception. Russia has been actively engaging with the Polisario Front and Algeria, as well as other military actors in the region, even providing military support through arms deals.11Nikonov, S. (2022) ‘Russia and MINURSO’, In Besenyő, J.; Huddleston, R.J.; and Zoubir, Y.H. (Eds), Conflict and Peace in Western Sahara: The Role of the UN’s Peacekeeping Mission (MINURSO), London: Taylor & Francis.

Nonetheless, this is inconsistent with the Russian pattern for two reasons. The first is that military support comes in the form of arms directly from the state, so contracted personnel are completely missing from the picture.12Giles, K. and Akimenko, V. (2019) ‘Use and utility of Russia’s private military companies’, Journal of Future Conflict, 1(1). Second, in contrast to Moscow’s position in countries such as Mali and Niger, the Kremlin has been very vocal and continuously advocated in favour of a referendum in Western Sahara with an independent organising committee led by the UN. Russia signed strategic agreements with Algeria and Morocco in 2002 and 2005, respectively, and wants to maintain relations with both parties, which can be seen as the main driving force behind its positive neutrality stance. In 2016, Russia asked for a revision of the MINURSO mandates so that they call for immediate action from both parties, with the ultimate objective of resolving the problems that have led to the current impasse and made carrying out the UN resolution impossible.13Plank, F. and Bergmann, J. (2021) ‘The European Union as a Security Actor in the Sahel: Policy Entrapment in EU Foreign Policy’, European Review of International Studies, 8(3), 382–412. Thus, it can be argued that Moscow is unlikely to change its balancing stance. The war in Ukraine has also depleted Russia’s financial, military and human resources. Hence, pursuing active support of either the Polisario Front or Morocco seems a relatively remote possibility.

Türkiye

Another state actor that has increased its military influence on the continent is Turkiye. Ankara has signed military agreements and deployed military attaches in more than 20 African countries over the past five years. Its flagship project in the defence industry in Africa has been its military base in Somalia, ensuring a presence in a passage of great strategic importance, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, which has increased in importance amidst the Houthis attacks and the conflict in Gaza. Trade volumes with Africa have increased from $5.4 billion in 2003 to more than $38 billion in 2022, which shows a clear intention of further engagement in other areas, the defence sector being just one.

Ankara has followed a rather pragmatist stance in its foreign policy in West Africa and the Sahel. President Erdogan recalled his ambassador from Morocco following remarks that clearly favoured Rabat regarding Western Sahara when he stated that the dispute is ‘purely artificial.’ At the same time, Turkiye is increasing its cooperation with Algeria, while maintaining its alliance with Morocco, in an attempt to maintain a balance. However, changes on a global scale might affect this stance.14Bradford-Adams, K. (2019) ‘Resistance and Complacency: Cold War Legacies and the Geopolitics of the Western Sahara’, Honour’s thesis, Seattle University. The conflict in Gaza has led President Erdogan, in several cases, to take a position in favour of Palestine, predominantly because of his endeavour to emerge as a leader of the Muslim world. The case with the Sahrawis is different, nonetheless, as the conflict concerns two Muslim peoples. However, the fact that one group is deprived of its sovereignty might eventually lead to a clearer stance on the independence of the Sahrawi Republic. The chances of this happening are small, although still more likely than the chances of a military intervention by Russian PMCs.

Regional military interventions

The final new trend that has emerged is the regional military support for state actors that face an internal crisis, such as where non-state actors are compromising the country’s security. Such examples include Southern Africa, where the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has supported the Mozambique government in the conflict against insurgent groups operating in Cabo Delgado. This pattern has already taken place in West Africa, with the Multinational Joint Task Force being an international actor of primarily military purpose and the end goal of combating the threat of Boko Haram, with the participation of Nigeria, Niger, Benin, Chad and Cameroon. Another example is the G5 Sahel, which attempted to resolve broader security matters in the region. The G5 was unsuccessful as, following the wave of changes to governments in three participating states, it has been left with Chad and Mauritania as its only members. Overall, such initiatives have not seen much success in West Africa, but it is of interest to see whether this can change in the case of Western Sahara.

There are two reasons why regional military interventions have the lowest likelihood of taking place. The first one is the contested status of Western Sahara. Unlike the previous cases, the Sahrawi Arab Republic is not recognised by all the states in the region. Hence, an intervention from its key ally, Algeria, would be highly controversial, even for the supporters of its independence. The chance of intervention to support Morocco may be higher, but questions remain about which regional countries would be prepared to intervene. Virtually all the regional powers rank below the 100th position in the Global Firepower Index, with Ivory Coast being the only one marginally above that mark. Nigeria is a strong military power and could theoretically intervene; however, its internal and border disputes would make this highly unlikely. Finally, a potential intervention would be tied to broad consensus on a regional level with regard to the status of Western Sahara and the need for intervention. This seems highly unlikely, as several countries are facing internal disputes, meaning there is a lack of appetite for regional intervention in Western Sahara.

Conclusion

In summary, the conflict in Western Sahara can be seen as unique, with regional and international actors lacking policy options to deal with the issue permanently. This paper indicated the main dynamics to look out for over the next years that might impact the Sahrawi situation. Currently, we are experiencing a historic shift, where new security guarantors are being introduced, with increasing participation of the private sector and new state actors coming to the fore in defence and security in Africa. Amidst these changes, it is of utmost importance to examine whether the West African stalemate will be affected. This paper has found that there remains a very small possibility for change to the current status quo. However, one must not rule out the emergence of new foreign policy forces that exercise hard power, such as Turkiye, as well as the possibility of regional actors with good development indicators, such as Ivory Coast, emerging as mediators. Finally, despite the weakening of Russia and its PMCs amidst the war in Ukraine, their involvement in the frozen conflict must not be ruled out.

Dimitris Symeonidis is an energy policy and geopolitical risk analyst, researcher and advisor. He is the founder of the Decentralised Solutions Global Network, where he specialises in geopolitical risk analysis and research of partially recognised states in Eurasia and Africa.