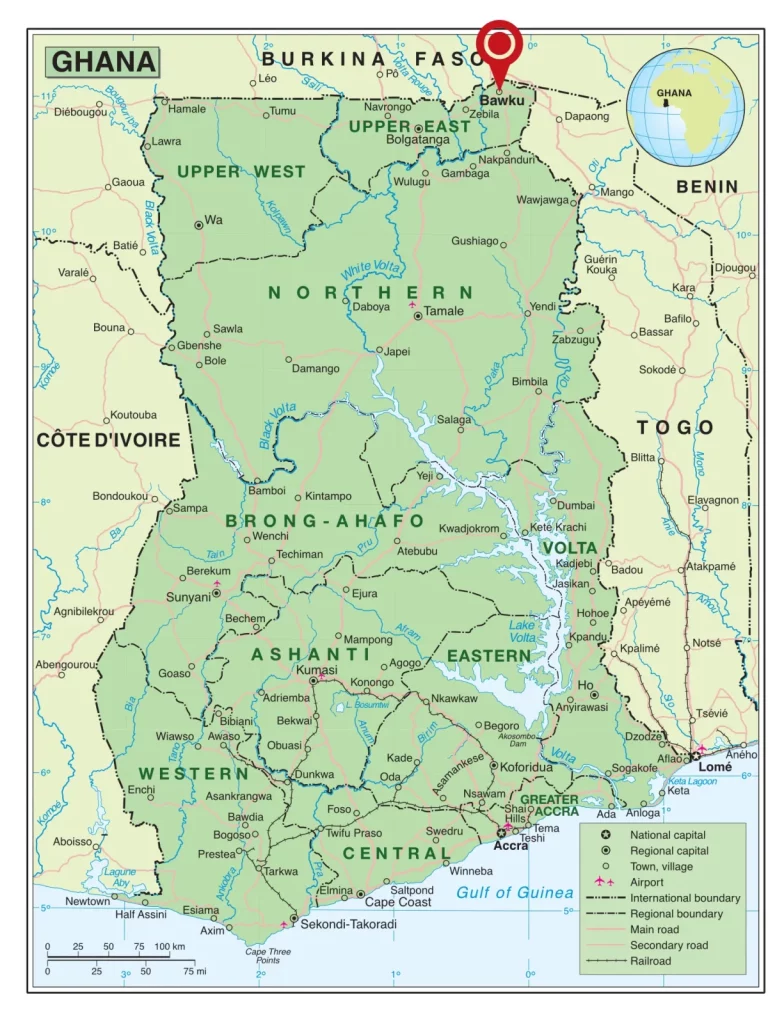

Bawku, a town located in the Upper East region of Ghana, has been gripped by prolonged tension stemming from persistent conflict, often marred by gun violence and fatalities. The deadliest periods were observed from 2007-2009 and post-2021. What sets apart the current armed conflict in Bawku is its duration, spanning over a year and a half and resulting in over 260 casualties in and around the area. The escalation is fuelled by arms trafficking and the proliferation of advanced weaponry. Unlike past clashes, which typically lasted days, this conflict persists with the use of automatic, sophisticated, high-calibre rifles, a departure from previously prevalent locally manufactured guns and small arms.1Interview with civil society, youths and police in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana; The Signal Room (2023) ‘Ghana – Let’s talk about Bawku’, 21 April, Available at: https://www.thesignalroom.com/ghana-lets-talk-about-bawku-236056119-1842092068 [Date accessed: 24 February 2024].

Linked to the use of arms, there are reports of extremist activities spilling over from the Sahel to areas like Bawku, Widnaba, and the borders surrounding the Nazinga forest in Ghana. While terrorism extends southward from the Sahel to coastal countries, Ghana has not experienced insurgent attacks compared to its neighbours. However, the government is apprehensive about potential spillover from jihadist activities in Burkina Faso, particularly with the influx of displaced Burkinabe across porous borders.2Ghana Ministry of the Interior (2023) ‘High-Level Dialogue on Burkinabe Refugees in Ghana Held in Accra’, 23 February, Available at: https://www.mint.gov.gh/high-level-dialogue-on-burkinabe-refugees-in-ghana-held-in-accra [Date accessed: 24 February 2024]. This concern is compounded by poverty in Bawku, increasing vulnerability to exploitation by criminal and jihadist groups amidst worsening economic conditions, and the proliferation of arms due to ongoing chieftaincy conflicts.3Committee on Defence and the Interior (2023) ‘Concerns raised by Committee on Defence and Interior about the proliferation of light weapons in communities in the north, especially Bawku’, Available at: http://ir.parliament.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/2723/Report%20of%20the%20Committee%20on%20Defence%20and%20Interior%20on%20the%202023%20annual%20budget%20estimates%20of%20the%20Ministry%20of%20National%20Security.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Date accessed: 20 December 2023]. Furthermore, Ghanaian state officials are worried that extremists may exploit the state of insecurity to target Ghana’s gold industry as a source of funding for their activities.4Sackitey, Daniel (2022) ‘Terrorists may take advantage of galamsey activity in Ghana – Kan Dapaah warns’, Citi Newsroom, 20 November, Available at: https://citinewsroom.com/2022/11/terrorists-may-take-advantage-of-galamsey-activities-in-ghana-kan-dapaah-warns [Date accessed: 24 February 2024].

This article delves into the complex relationship between armed violence in Bawku and the drivers of armed conflict and its potential links with terrorism. By examining this nexus, the article seeks to provide insights into the phenomenon that is key to informing responses that will contribute to stability in Ghana. The article begins with an examination of armed violence in Bawku and its potential links to terrorism. An analysis of the underlying drivers and the impact of armed violence on the community is provided.5The data for this article is derived from interviews with various stakeholders, comprising representatives from civil society organisations, youth groups, ethnic leaders, journalists, police officials, and traditional leaders. Interviews were conducted in Bawku, Tamale, Bolgatanga, and Nalerigu during April 2023. Additionally, focus group discussions were organised with youth groups in Bawku to delve into the socio-economic impacts of the conflict and explore youth perspectives on the subject.

Armed violence in Bawku and links with terrorism

In April 2022, communication from the police headquarters to the Upper East Regional Police Command confirmed the involvement of Burkinabe fighters from the province of Boulgou in Burkina Faso in the armed conflict. It was also confirmed that arms were smuggled from Burkina Faso, although no links with terrorist cells were proven. The communication suggested that Burkinabe fighters’ involvement in the gun battles may have been motivated by ethnic ties and financial interests.6Ghana Police Service (2022) ‘Re – Burkina national involved in armed conflict’, Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/6drp0h6ydf2mjam/PHOTO-2023-04-19-13-06-31.jpg?dl=0 [Date accessed: 15 May 2023]; Interview with ethnic group leader in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana.

The security situation in Bawku not only provides a conducive environment for jihadists and violent extremists to infiltrate and radicalise the local community but also poses a serious threat due to the influx of Burkinabe fighters from Boulgou province. Reports indicate that jihadists with family ties in Bawku are being actively recruited to join the fighting. Additionally, factions are reaching out to armed robbers and criminals on the streets, further exacerbating the security risks.7Interview with journalist and civil society in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana. Furthermore, socio-economic challenges and lack of job opportunities make young people in border communities open to joining jihadists.8Interview with ethnic youth leader in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana.

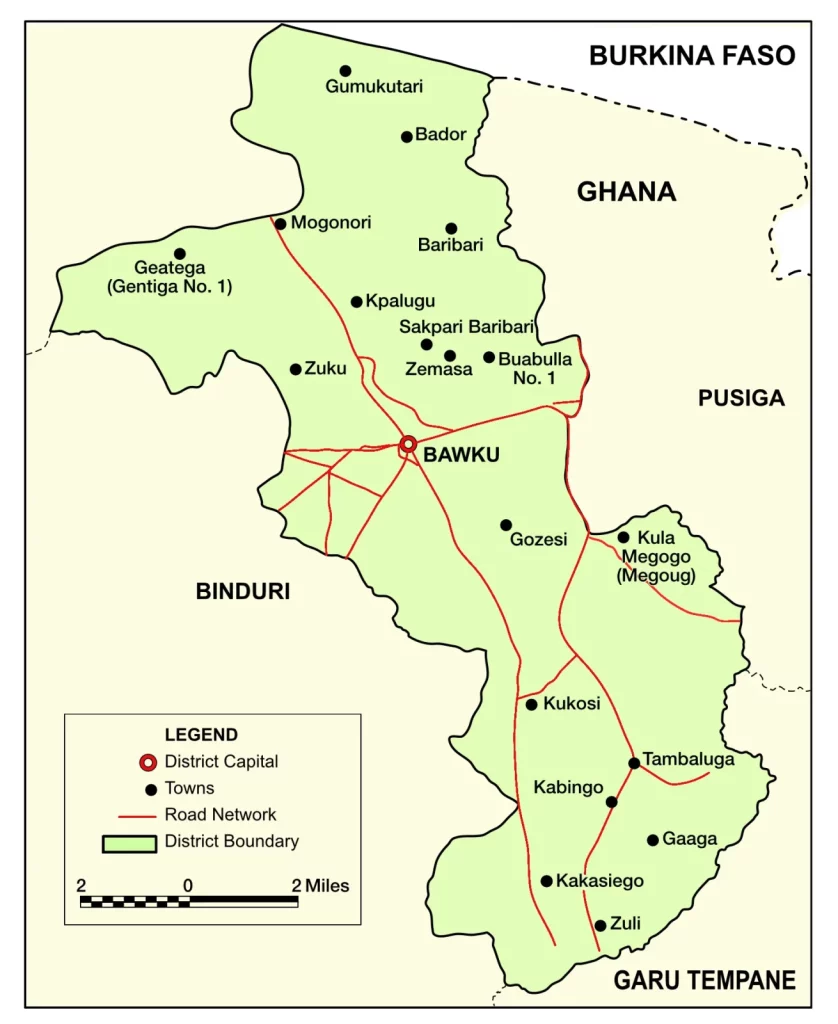

Jihadist terrorists in Burkina Faso are attempting to infiltrate some of the border areas of the Upper East. In the areas around Pusiga, Pulmakom, Kulungungu, Widnaba, Widana, etc., jihadist cells and hideouts have been confirmed by numerous high-level sources.9Nartey, Laud (2022) ‘Soldiers deployed to Kulungungu, others near Bawku over suspected Jihadist attack’, 3News, 31 January, Available at: https://3news.com/news/u-e-soldiers-deployed-to-kulungungu-others-near-bawku-over-suspected-jihadist-attack [Date accessed: 15 May 2023].

In February 2023, chaos broke out in the Pinda community, close to the Paga border with Burkina Faso, after the local populace purportedly spotted many armed men on motorcycles in a nearby forest. In a related incident on 23 April 2023, the Burkinabe army conducted air strikes in the Boulgou province along the Ghanaian border near Widnaba in the Upper East region. The army announced that it had targeted a terrorist cell and killed several suspected terrorists at the border. This was after reports of active recruitment by a Togolese Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) fighter along the Ghanaian border.10Burkina Information Agency (2023) ‘Burkina: Terrorists neutralised in their comfort zones, 23 April 2023’, Available at:https://www.aib.media/2023/04/23/burkina-des-terroristes-neutralises-dans-leurs-zones-de-confort/?fbclid=IwAR2p0qnhCL3YuBwsLybTLWoXSylJe85e6QbK-Hh2KJ5kygENtWh4G1h7M0o [Date accessed:15 May 2023]. In addition, studies estimate that 200 to 300 Ghanaians have been recruited by jihadists across the border for training and then sent back to their home villages to engage in religious proselytisation.11Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (2023) ‘The Jihadist Threat In Northern Ghana and Togo: Stocktaking and Prospects For Containing The Expansion’, Available at: https://www.kas.de/documents/261825/16928652/The+jihadist+threat+in+northern+Ghana+and+Togo.pdf/f0c4ca27-6abd-904e-fe61-4073e805038a?version=1.0&t=1652891434962 [Date accessed: 16 June 2023].

Ghana remains the preferred location for the sale of stolen or confiscated firearms. In this regard, JNIM is rumoured to have numerous meeting points and hideouts on the Ghanaian side of the borders with Togo and Burkina Faso. JNIM also relies on Ghanaian couriers and dealers for its oil supplies, although there are no indications of imminent plans to attack or engage in violent aggression in Ghana. The Ghanaian security forces in the Upper East region conducted an ‘in-road’ operation on Burkinabe territory, arresting and delivering more than ten terrorist suspects to the Burkinabe government. There are fears that the influx of Burkinabe12In February 2019, 275 people fled to Ghana due to chieftaincy clashes and associated violence in Burkina Faso. In February 2023, more than 4 000 Burkinabes emigrated from their homeland to Ghana to seek refuge as a result of Jihadist assaults. They gained entry into Ghana by crossing the borders in the towns located in the Upper East and Upper West Regions of Ghana. from the southern border of Burkina Faso (namely Bugri, Zouga and Asongo) into Ghana, specifically Soogo in the Bawku West district, poses a serious threat to Ghana’s security due to reported attacks by jihadists. The seriousness of the insecurity in Burkina Faso is such that weapons have been handed over to Burkinabe volunteers within communities to defend themselves against jihadists, which may fuel the trafficking and illicit circulation of small arms and explosives.13Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Tamale, Ghana.

Reports indicate that violent extremist groups came from Burkina Faso to Sapeliga and Soogo and warned Burkinabe citizens who migrated to Ghana to return the arms given to them by the Burkinabe government to protect themselves. There are also reports of people believed to be jihadists who were shot and killed in the Kayoro forest (located approximately 57 km (35 miles) away from Bolgatanga).14Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Bolgatanga, Ghana; Focus group discussion with youth group in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana.

In another example of jihadist incursions, several community sources confirmed the arrest of four people at one of the border crossings at Widana in the Upper East Region. According to community sources who witnessed the arrest in Bawku, the four people are suspected jihadist militants who were on their way to the Ivory Coast from Burkina Faso. According to the same sources, the suspects were armed and in possession of 36 million Central African francs (CFA) (equal to almost US$60 000 at the time of writing). According to these sources, the suspects were flown from Bawku to Accra and handed over to the National Bureau of National Investigations. At the time of writing, no official statement had been issued, as Ghana’s security services do not inform the public of their counter-terrorism efforts in the north. It is also unusual for local suspects in the Bawku theatre to be taken to Accra for further investigation.15Interview with journalist in April 2023 in Nalerigu, Ghana. On 18 April 2023, a traditional leader from Bawku stated: “We will not allow them to cow us in. We will sacrifice all we have to buy guns to protect ourselves. About seven people have died in my community from August 2022 till March 2023.”

The drivers of armed violence

Chieftaincy, political considerations, perceived slow response by state security forces, commercial interest, and the apparent influence of illicit actors have been driving arms trafficking in Bawku. These factors will be described in this section.

Chieftaincy: The protracted chieftaincy conflict had triggered the trafficking and use of sophisticated arms. First, parties to the conflict believe that without sophisticated weapons, they will be overpowered by the other. As a result, warring factions solicit funds from family members outside Bawku and abroad to purchase weapons or request that weapons be sent to them. Young people also believe that the possession of weapons acts as a deterrent against attacks from an opposing group and that stockpiling arms is key to preparing adequately for future clashes. Despite relatively low income levels, community members are reported to contribute to the purchase of weapons for the community to be used by the youths in preparation for possible attacks. When this happens, other ethnic groups in the minority conflict contribute out of fear of being victimised.16Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Tamale, Bolgatanga and Bawku; Interview with police and youth group in April 2023 in Bawku. Groups are also armed by their tribespeople outside Bawku to display solidarity and support for their ethnic group.17Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Bolgatanga, Ghana. This strategy was used in 2019 during the ethnic (Chokosi-Konkomba) conflict in Chereponi, where tribespeople and non-tribespeople from Togo were recruited by both sides to fight.18Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Tamale, Ghana; Peace FM Online (2019) ‘Togolese Arrested Over Chereponi Conflict’, 26 March, Available at: https://www.peacefmonline.com/pages/local/news/201903/378739.php [Date accessed: 15 May 2023].

Political: During the transition of political regimes from one political party to another after an election, ethnic elites from both factions (the Mamprusi and Kusasi) mobilise their respective populations and resort to violence when the political climate is favourable. Elites from different groups may use legal processes to demand equality, redistribution of resources, bureaucratic access, power, or natural resources. The political strategy used by political parties in power leads the people to believe that they have been subjugated, oppressed, and denied justice or access to their rights. This generates feelings of anger and resentment. Armed conflict thus erupts when the capacity and opportunity exist. There is political control as armed men depend on the support and goodwill of political actors from Bawku and adjoining towns. The political actors capitalise on the conflict for political gains.19Tseer, Tobias; Sulemana, Mohammed; and Marfo, Samuel (2022) ‘Elite mobilisation and ethnic conflicts: evidence from Bawku traditional area’, Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), art. no. 2123137.

In addition, political actors and ethnic elites in Bawku mobilise people along ethnic lines in favour of specific political parties. This often creates political favouritism for each ethnic group, depending on the political party that emerges victorious in elections. Ethnic groups expect the political parties they support to use state powers via security forces or court processes for their political gain.20Tseer, Tobias and Halidu, Musah (2023) ‘Ethnic plurality, political mobilisation, social divisions and the formation of conflict structures in North-Eastern Ghana’, Political Science International, 1, 1–10. For example, in 1983, the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) junta allowed the Kusasi group to reclaim the Bawku chiefdom. In total, 37 people were killed when the Mamprusi attacked the National Democratic Congress (NDC) celebration. After the decision and the violence, the NDC and Kusasi formed a local alliance. Kusasi people became members of the NDC and used their influence to promote their interests in trade, markets and the flow of goods in Bawku, exacerbating tensions between the Kusasis and Mamprusis. Bawku was further politicised in 1992 with the formation of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP). To reverse the 1983 NDC move, the Mamprusi supported the NPP.

To protect their community interests, Mamprusi and Kusasi leaders gradually supported the NPP and NDC, respectively, in the run-up to the 2000 parliamentary and presidential elections. Violence erupted during the counting of votes in Bawku after NDC and NPP officials disputed the results. The fighting, which left 68 people dead, ended with a military curfew. John Kufuor of the NPP won, but he did not change the Bawku chiefdom despite Kusasi concerns. In Ghana’s 2008 elections, which returned the NDC to power, communal tensions erupted into violence. At least five people were killed before the military was deployed and a curfew was re-imposed in Bawku. This has been the trend in political alignment by the Kusasis and Mamprusis to date.21Interview with ethnic youth leader in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana; The Signal Room (2023) ‘Ghana – Let’s talk about Bawku’, op. cit.

Perceived slow response by state security forces: The inhabitants attribute the proliferation of arms to the state security apparatus, which has failed to guarantee their protection, thus leading to the local communities acquiring their own weapons to protect themselves. During gun battles, other criminal actors loot shops, resulting in shop owners procuring guns to protect themselves and ward off looters. According to one youth group, “guns are now used as first aid before the police and military come.” This is because the state security forces are often slow to react to distress calls.22Focus group discussion with youth leader in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana.

Commercial interests: Those with commercial interests, such as businesspeople, provide funds for the purchase of arms and incite others to drive commuters and traders to the highway transport market (controlled by Kusasis) rather than the main market (controlled by Mamprusis). When this happens, “conflictpreneurs” profit from the trafficking of arms and ammunition.23Interview with traditional leader, civil society and police in April 2023 in Bawku, Ghana; Ghanaweb (2023) ‘Ambrose Dery issues warning to Bawku conflict perpetrators’, 3 January, Available at: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Ambrose-Dery-issues-warning-to-Bawku-conflict-perpetrators-1689764 [Date accessed: 15 May 2023].

Influence of illicit actors: The rise in banditry and robbery has triggered the demand for arms.24Interview with civil society in April 2023 in Tamale and Bolgatanga, Ghana.

Conclusion

The research findings shed light on the complex dynamics driving arms trafficking in Bawku, Ghana. Chieftaincy disputes, political considerations, perceived shortcomings in state security responses, commercial interests, and the influence of illicit actors have all contributed to the proliferation of sophisticated weaponry in the region.

Chieftaincy conflicts have acted as catalysts for the trafficking and use of advanced arms, fuelled by ethnic groups’ fear of being overpowered and their perception of weapons as deterrents against attacks. Political transitions have further exacerbated tensions, with ethnic elites mobilising populations along ethnic lines for political gain, leading to violence and polarisation. Perceptions of slow responses by state security forces have eroded trust in official protection mechanisms, prompting individuals and groups to arm themselves for self-defence. Additionally, commercial interests and the activities of conflict entrepreneurs have driven the demand for arms, with profit motives exacerbating the conflict. Furthermore, the influence of illicit actors, including bandits and robbers, has fuelled the demand for weapons, perpetuating a cycle of violence and insecurity in the region.

In light of these findings, addressing the root causes of armed violence in Bawku will require a multifaceted approach, including efforts to resolve chieftaincy disputes, strengthen state security responses, curb illicit arms trafficking, and promote inclusive governance and economic development. Only through concerted and collaborative action can sustainable peace and stability be achieved in Bawku and similar conflict-affected regions.

While the conflict is expected to remain localised in Bawku, there is a risk of violence spreading to other areas, including the northeast and neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso. As Ghana approaches the December 2024 elections, election-related activities in Bawku could exacerbate the violence, especially given the historical political alignment, political tensions, and economic challenges facing the country. Additionally, extremist groups may seek to expand their influence into Ghana to challenge the government’s foreign policy, potentially leading to further instability. Moreover, these groups could exploit artisanal mining sites in the north to fund their activities. Overall, the complex nexus of these factors poses significant challenges to peace and stability in Bawku and the wider region, necessitating comprehensive and proactive measures to address the root causes of conflict and mitigate the risk of further violence.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime’s (GI-TOC) Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa for supporting this work.