In the heart of Central Africa, the management of transboundary water resources stands as a pivotal arena where the complexities of national interests converge with the imperative of conflict prevention and regional peacekeeping. The equitable distribution of shared rivers, lakes, and aquifers necessitates collaborative frameworks to navigate the intricacies of interdependence among riparian states. This article delves into the nuanced landscape of transboundary water governance, with a keen focus on the regulatory measures implemented in the Lake Chad and Congo Basins. Emphasising the integral role of community legal instruments in mitigating potential conflicts, the discussion extends to the challenges that hinder comprehensive adherence to international water conventions. Against this backdrop, the narrative unfolds to reveal the dynamic interplay between national interests and the overarching goal of regional harmony. As we traverse this exploration, the article not only sheds light on the emerging trends in Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) in Central Africa but also proposes strategies for conflict prevention and the promotion of enduring peace within the region’s shared water ecosystems.

Introduction

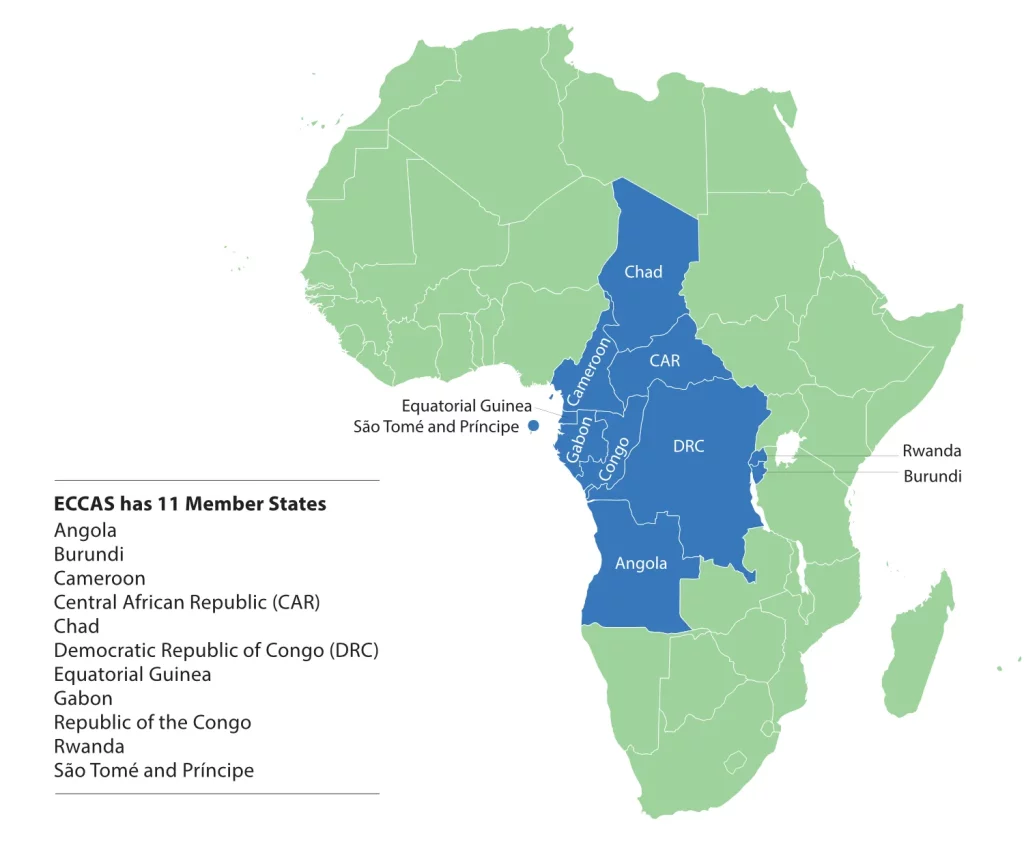

The equitable and sustainable management of transboundary water would require cooperation as it involves many interdependencies. Indeed, the problem of water sharing has strong repercussions at the international level, be it through threats of war, the exacerbation of power relations, or the consolidation and/or weakening of alliances.1Allouche, Jérémie and Daoudy, Marwa (2010) ’L’hydropolitique et les relations internationals’, Dynamiques internationales, 2: 1–4. For the optimists,2Ayeb, Habib (1998) ‘L’eau au Proche-Orient: la guerre n’aura pas lieu’, Karthala-CEDEJ, Paris; Wolf, Aaron (1998) ‘Conflict and Cooperation along International Waterways’, Water Policy, 1(2): 251–265; Selby, Jan (2005) ‘The Geopolitics of Water in the Middle East: Fantasies and Realities’, Third World Quarterly, 26(2): 329–349; Selby, Jan (2005) ‘Oil and Water: The Contrasting Anatomies of Resource Conflicts’, Government and Opposition, 40: 200-224; Trottier, Julie (2003) ‘Water Wars: The Rise of a Hegemonic Concept – Exploring the Making of the Water War and Water Peace Belief within the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’, in Hassan, Fekri A. (Ed.), History and Future of Shared Water Resources, Paris: UNESCO, pp. 51–64. the war for water is too costly to be undertaken and non-cooperation does not benefit the riparian countries. Thus, cooperation between riparian states in Central Africa would be the best option to prevent conflicts through the regulation of national interests on the shared resource in community documents and legal instruments. However, the existing documents cover only two basins, while the region is made up of 16 shared rivers and five shared lakes as surface water resources, 17 aquifer systems that are shared between two or more of the ten countries in the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), or between two or more countries outside the community space as groundwater resources, and 15 wetlands classified under the Ramsar Convention. It is of interest to look at a more global framework for the prevention of water-related conflicts in the region and to analyse the States’ adherence to existing instruments.

Prevention of water conflicts in Central Africa through the regulation of national interests in their community legal instruments

The pursuit of national interests over shared resources can be a source of conflict. However, in the Lake Chad Basin and the Congo Basin, there are framework texts that contribute to the regulation of national interests and the prevention of conflicts.

Regulation of national interests for conflict prevention in the Convention of the Lake Chad Basin Commission

The Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) involves regulatory measures addressing the national interests of Member States on both substantive and procedural levels. Substantively, these measures pertain to the management, use, exploitation, and sharing of water resources. Procedurally, they encompass the establishment and overall governance of the LCBC. Article 5 of the bylaws states that: ‘Member States undertake to refrain from taking, without prior consultation with the Commission, any measures likely to have an appreciable influence on the extent of water loss, the shape of the annual hydrograph and limnograph, and certain biological characteristics of the fauna or flora of the basin.’

The 1964 Convention and Statutes Relating to the Development of the Chad Basin introduced principles of equitable and reasonable use, akin to the customary principle (that was not enshrined), and laid the groundwork for Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), as seen in the Dublin Conference. This means that the Lake Chad Basin Charter, by adding details to the agreements established in 1964, enhances the rules and principles related to water resource management in the region. It promotes an approach that considers sustainability, integration, and collaboration in the management of the water basin.

However, the Charter clarifies and complements the 1964 founding instruments and integrates the sustainable, integrated and concerted management of the basin’s water resources. It ensures the protection of shared waters, which is in the common interest of the Member States ‘Considering that the sustainable management of the Basin must closely associate the main stakeholders, namely users, managers, political decision-makers, experts from the scientific world and civil society organisations.’ The Charter, therefore, contributes to the regulation of national interests for at least two reasons. On the one hand, it takes into account the universal conventional and customary rules and principles of the general law of international watercourses, as codified in the 1997 Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, while ensuring that the relationship between the regional and the universal is maintained. On the other hand, it contributes to the channelling of the national interests of the Member States through the promotion of IWRM. The Charter encourages IWRM by focusing on collaboration among various actors, such as water users, water resource managers, policymakers, scientific experts, and civil society organisations. This collaborative approach aims to prevent potential conflicts related to water use and management in the Lake Chad Basin region.

Regulation of national interests for conflict prevention in the Agreement Establishing a Uniform River Regime and Creating CICOS and its addendum

The pursuit of a common interest inherently serves as a mechanism to reconcile national interests concerning shared resources, as exemplified in the Vienna Convention. Article 108 of this Convention stipulates that States through which the same watercourse flows are obligated to resolve any matters pertaining to this aspect through mutual agreement.3Parry, C. (1969) ‘Act of the Congress of Vienna, signed between Austria, France and Great Britain, Portugal, Prussia, Russia and Sweden, 9 June 1815’, Consolidated Treaty Series, 64, P 490, New York: Oceana Publications.

Thus, throughout the Agreement Establishing a Uniform River Regime and Creating the International Congo-Ubangui-Sangha Commission (CICOS), along with its addendum, there is a clear intention to prioritise the common interest over national interests. Countries are provided with the option to enter into bilateral agreements in specific cases. In the initial chapter, Article 1 not only defines the term ‘riparian State’ to encompass the founding Members but also extends the scope to include other States whose territories are partially or entirely covered by a waterway of the Congo-Oubangui-Sangha basin. This inclusion of additional riparian countries signifies a commitment to considering all interests, particularly in navigation and related fields. Moreover, the endorsement of community management for shared waters, as outlined in these foundational instruments, represents a proactive measure in preventing water conflicts.4It may be noted that several cases in the field of water have been brought by certain commissions and basin organisations’ Member States. These include the advisory opinion on the competence of the European Commission of the Danube between Galatz and Brăila (1927) and the case concerning the territorial jurisdiction of the Oder (1929).

Given the increasing intricacies associated with shared water usage, CICOS deemed the regulation of such usage imperative. This commitment is manifested in specific articles addressing crucial aspects, such as the right of transport (Article 5), the right and taxation of navigation (Article 6), the obligation for the maintenance and improvement of waterways (Article 7), and the regulation of water flow (Article 3). Article 15, titled ‘Benefit of Solidarity,’ underscores the concept of sovereign sacrifice for the community’s welfare, illustrating CICOS as a platform where dialogue and collaborative actions transcend political contingencies. The primary focus remains on the sovereign interest in this shared resource. Furthermore, an addendum revised the original Agreement to actively ‘promote integrated water resources management in the Commission’s area of jurisdiction.’

Despite the aforementioned factors, it is evident that certain areas lack institutionalisation, underscoring the importance of adhering to international and regional conventions to pre-empt conflicts over shared water resources. It is crucial to highlight that Chad and Cameroon are the sole countries in the region that have ratified an international water convention. Consequently, the challenge of averting long-term water conflicts persists.

The challenge of preventing water conflicts in Central Africa

Alternative measures for averting water conflicts in Central Africa include engagement with international water conventions and the ECCAS Convention. Nevertheless, there is hesitancy among countries to commit to these instruments.

Analysis of the non-adherence of Central African States to international water conventions

The attainment of independence by African countries endowed them with international competencies, including the authority to engage in treaties. The ratification of such conventions necessitates a specific act by public authorities (law, decree, proclamation, etc.), as per the constitutions of these countries, integrating them into domestic law and potentially impacting national interests. Therefore, whether concerning water conventions or other types of agreements, States retain sovereignty in deciding whether to join a specific convention, contingent upon economic and social considerations. The conditions, including priorities and interests, must be carefully considered.

In the specific case of these two conventions, the issue of accession must be contextualised within a global framework. These conventions address transboundary cooperation and incorporate mechanisms to prevent conflicts. The management of water resources that traverse borders introduces significant complexity, given that each State holds a distinct perspective on resource management, utilisation, and investment projects. Cooperation necessitates collective action and the imposition of regulations, contrasting with a unilateral approach where a country can independently manage the resource for its benefit. These complexities are evident in the prolonged negotiations spanning two decades on the adoption of rules under the 1997 Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. Furthermore, during the final vote, not all States endorsed the Convention, and it took an additional 17 years to reach the quorum of 35 States for it to enter into force, as specified in Article 36.

The challenges may also stem from the difficulties posed by Articles 5 to 7 in the 1997 Convention, addressing equitable and reasonable use, as well as the obligation not to cause damage and to compensate. These clauses, likely contributing to challenges in the comprehensive adoption of the New York Convention, could impede States’ commitment due to potential conflicts between upstream and downstream countries along international watercourses.5In 1991, a first draft of 32 articles received comments from governments and was adopted by the International Law Commission (ILC). It was only three years later that the ILC adopted a draft of 33 articles and a resolution on transboundary groundwater. Since its entry into force in 2014, three States have been added, making 38 States worldwide. ILC (1993) ‘The law of the non-navigational uses of international watercourses’, ILC Yearbook, II(1): 93–143.

The Helsinki Convention has a distinctive history, using the pan-European region as a testing ground to assess its effectiveness and relevance. States in this region actively contributed to refining and demonstrating the practicality of the Helsinki Convention’s mechanisms through agreements. Amendments to Articles 25 and 26 expanded the Convention’s scope, enabling United Nations (UN) Member States outside the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) region to become parties. Notably, out of 56 States, 41 had joined before Chad, Senegal, Cameroon and Ghana, the sole African countries to date to have joined.

As the Central Africa region is still in the process of development, there is a considerable learning curve. Despite having institutions like the LCBC, CICOS, and the Ruzzizi Basin Authority, West and Southern Africa have more experience in transboundary management. While Central Africa is not averse to cooperation or convention adherence, there is a need for a comprehensive understanding of universal rules, promotion, explanation, and training, all of which require a progressive, time-consuming process. Adherence to these conventions is gradual, grounded in the strategic importance of water resources, with States yet to fully grasp the benefits of such cooperation.

In reality, these conventions present significant future prospects for Central African countries. Fundamentally anchored in the principle of state sovereignty (limited sovereignty), their effectiveness raises questions about protecting the watershed as a whole, transcending individual State interests.6Lasserre, Frederic and Cárdenas, Yenny (2016) ‘The entry into force of the New York Convention on the use of international watercourses: what impact on the governance of international basins?’ Revue Québécoise de droit international, 29(1): 85–106. It is crucial to recognise that contemporary water management, despite its ancient roots, is still in its nascent stages of formalisation. Basin organisations in Africa emerged post-independence, experiencing a surge in the early 1990s, yet they remain works in progress. Understanding and aligning with cooperation frameworks at various levels is inherently time-consuming, given the gradual nature of the process, contingent upon evolving circumstances and opportunities. Central Africa exhibits positive developments in adopting IWRM over nearly two decades, alongside the ongoing implementation of ECCAS on the ground.

However, the political dynamics, characterised by a non-linear progression, initiate the adherence process in most interested Central African countries. Challenges arise from internal institutional structures that prioritise promotions and assign public officials independently of ongoing processes, occasionally necessitating a restart with new actors unfamiliar with their predecessors’ work. These complexities hinder States’ adherence, underscoring the necessity to comprehend State support through the lens of foresight, sociological factors, developmental levels, prioritisation of the issue, and the eagerness to establish independent instruments.

Understanding the prospects for ratification of the ECCAS Convention on the Prevention and Resolution of Water Conflicts in Central Africa

In Africa, the longstanding tradition of crafting new legal frameworks to address continent-specific water issues is not new, providing a justification for ECCAS’s engagement in this domain. The regulatory approach to transboundary waters here is uniquely multidimensional, incorporating the universal, regional, and basin-specific frameworks that generate normative tools. This prompts a legitimate inquiry into the necessity of adherence to all these levels. Unlike other domains, such as biodiversity with the Convention on Biodiversity or wetlands with the Ramsar Convention, transboundary water management operates on a multilevel regulation model tailored to the unique characteristics of this field. Water resources, inherently geographic management entities, not only stand alone but also form part of larger management perimeters encompassing entities like the LCBC, ECCAS, and CICOS within broader global frameworks.

To foster cooperation, it is imperative to establish a set of rules at various levels. The charters adopted within specific basins, such as the Congo Basin and Lake Chad Basin, will consider the nuances of their respective spaces. Simultaneously, the ECCAS charter guarantees a certain level of harmonisation across these geographical management areas to prevent distorted rules that may lead to tensions, particularly in cases where States share different basins with other countries. For instance, Cameroon and the Central African Republic (CAR) share both the Congo Basin and the Lake Chad Basin; having distinct rules in these areas complicates arbitration and management during disputes. Through its legal framework, ECCAS provides a structure for harmonisation, general management, and regulatory rules applicable to all its sub-areas of management. ECCAS is well-defined within a region but also aligns with global regulations, ensuring consistency across regions and adhering to principles that facilitate conflict prevention. Leveraging a universal framework, ECCAS formulates its structure based on widely accepted general rules, increasing the likelihood of ratification by Member States.

Conclusion

In consideration of the above discussion, it is evident that the legal framework established by basin river organisations in Central Africa can regulate the national interests of Member States, thereby influencing dispute resolution endeavours. While drawing connections between the political and legal realms might be construed as ‘legal fetishism,’ we are not asserting that law is the sole or indispensable determinant for regulating national interests, acknowledging the potential for debate on this matter. Nevertheless, this article underscores the significance of a robust legal framework in governing national interests and, by extension, in averting water conflicts in Central Africa.

Dr Michèle Désirée Nken née Okala Abega obtained a PhD in Political Sciences and International Relations from the International Relations Institute of Cameroon. She is an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Yaoundé and a Researcher at the African Research Centre for Energy and Mining Policies.