Introduction

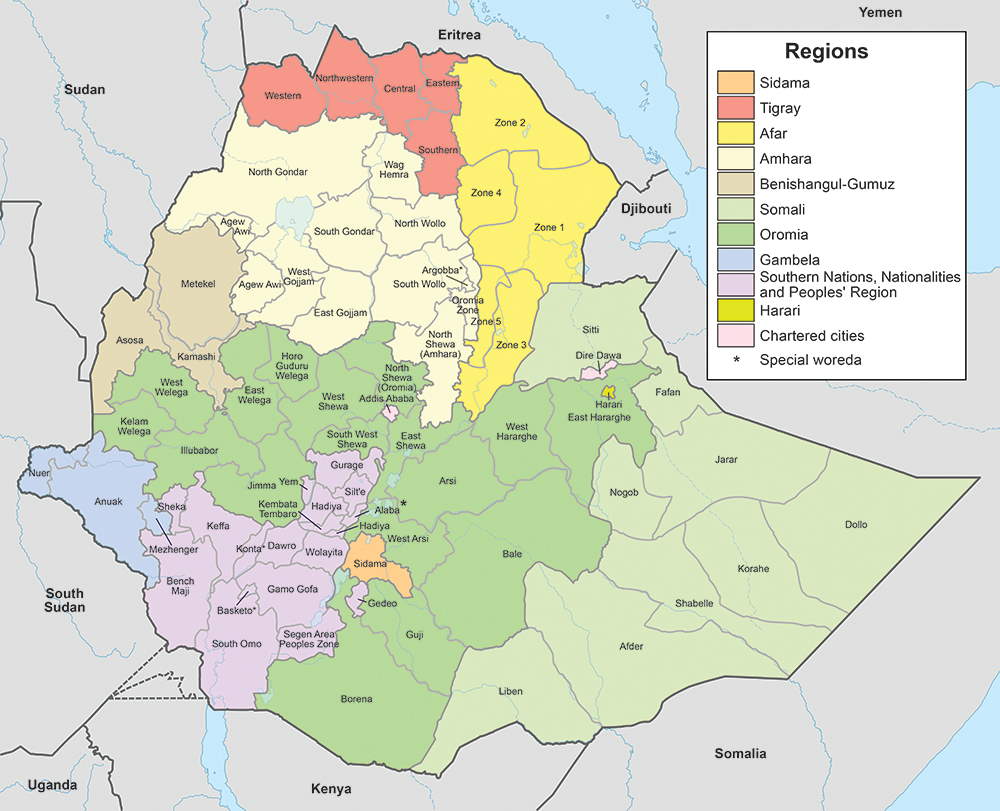

This article1 presents an overview of the seven most salient fault lines that confront Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in his attempt to transition Ethiopia towards democracy since taking power in 2018. Internally, Oromo, Amhara, Tigray, Somali and the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region each present their own challenges, which are difficult for any leader to reconcile. Externally, relations with Egypt and Eritrea are most consequential in determining where Ethiopia’s fragile transition to democracy is headed. A number of troubling developments, both in Ethiopia and within the region, raise concerns over how the country’s elections, now scheduled for 2021, will unfold. Ahmed mayhave entered the scene with good intentions, but is now faced with the enormous difficulties inherent in managing multi-ethnic states in Africa during transitions to democracy. The dilemma is that many of the necessary moves to democratise and quell the protest movements have concurrently weakened the state, unleashing various forms of group conflict. Ahmed’s recent efforts to re-exert the state’s power have involved various repressive tactics, such as silencing critics, arrests and internet shutdowns, which have also heightened tensions.

Challenges

Unrest in Oromia

First, Ethiopia’s unrest has been most acute in Oromia, where protests erupted in 2014 because of the federal government’s plan to increase Addis Ababa’s jurisdiction over parts of the Oromia region. More broadly, demonstrators were motivated by the rising cost of living and rampant unemployment, the Tigray People Liberation Front’s (TPLF) dominance within the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the pliant nature of the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO) within the EPRDF and the region’s history of being neglected and exploited by successive central governments in Addis Ababa. Waves of protests forced the EPRDF to formally abandon its “Master Plan” in January 2016 and to change the OPDO leadership, appointing Lemma Megersa as OPDO chairman in September 2016.2 A month later, anti-EPRDF protesters took over the annual Oromo Irreechaa festival in Debre Zeit. Security forces fired into the crowd, setting off a deadly stampede. On 9 October 2016, after protesters blocked the main roads in Oromia and then attacked government properties and foreign businesses, the government declared a state of emergency.3

The state of emergency led to the creation of a Command Post, dominated by the army, to essentially replace the cabinet. This had the power to deploy the army nationwide, shut down communication lines, limit freedom of speech and make arbitrary arrests. The government’s heavy-handed response, which included police shootings of protesters, the arrest of about 12 500 people and declaring two states of emergency, did not quell the unrest.4 In response, the government announced a major cabinet reshuffle in November 2016 and began releasing a number of political prisoners in January 2018. Despite these concessions, an Oromo youth movement, called Qeerroo (meaning “young bachelor” in Afaan Oromoo), tried to block the capital’s main streets. On 15 February 2018, the crisis forced Hailemariam Desalegn to resign as both prime minister and EPRDF chairman. Megersa, as OPDO chairman, was part of a team that selected Ahmed as prime minister. Many in Oromia celebrated Ahmed’s April 2018 ascension to the premiership, believing he would deliver a greater share of political power and economic growth.5

Since Ahmed took power, strikes in Oromia have been linked to the negotiated return to Ethiopia of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in August 2018, which was accompanied by rioting Qeerroo youth groups in the capital and its outskirts in Oromia.6 Addis Ababa and the Oromia region were hit by another wave of violence after the 29 June 2020 assassination of a prominent Oromo musician and political figure, Hachalu Hundessa. Qeerroo youth staged protests, destroyed property and attacked members of other ethnic groups, prompting non-Oromo communities to mobilise in self-defence. Hundreds of deaths resulted from clashes between armed gangs and the police. The government’s response was to shut down the internet and to deploy the military in the streets of Addis Ababa. Police also detained Jawar Mohammed and Bekele Gerba, two leading members of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), during a confrontation between security details.7

The three most significant political parties in Oromia are the OFC, OLF and Oromo National Party (ONP). The OFC, led by Gerba and Merera Gudina, also includes Mohammed – a formerly exiled journalist who played a leading role in mobilising protests in Oromia from 2014 to 2018 – within its ranks. The OFC leadership initially supported Ahmed but has recently become more critical, reproaching the new prime minister for centralising power, promoting a nationalising vision (“Ethiopiawinet”) that threatens Oromo identity and not fulfilling his promises to Oromia since taking office. The OLF is a former rebel movement, established in 1973, which was among the groups that defeated Mengistu Hailemariam’s communist Derg regime in 1989. The OLF soon came into conflict with the incoming EPRDF regime and was forced into exile, until Ahmednegotiated a deal in 2018 that allowed the group’s leaders to return to Ethiopia. The front’s former military wing, the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), parted ways with an already fragmented and splintered OLF in October 2018. The ONP party was established in November 2018 by Kemal Gelchu, a former senior OLF figure.8

Ahmedis trying to thread the needle between pleasing the protesters in Oromia while not alienating the country’s other ethnic groups. The aspirations of Oromo nationalists include enhanced devolution of power from the centre, ending the region’s economic marginalisation and establishing a formal role for the opposition in planning the next election. Many Oromo leaders accuse Ahmed of promoting a “neo-Neftegna” mentality. This is a nebulous and highly contentious term that once referred to Amhara riflemen, but is now associated with Amhara dominance over Oromia and of Ethiopian politics. Non-Oromo people often accuse Ahmed of favouring his own ethnic constituency by showing leniency in dealing with Oromo abuses, the OLF insurgency and provocations from hardliners like Mohammed. In January 2020, the OFC, OLF and ONP formed the Coalition for Democratic Federalism, with the goal of presenting a united front in the upcoming elections. The solidification of this alliance among Oromo factions would present a challenge to the electoral prospects of Ahmed’s Prosperity Party in Oromia.9

Protests in Amhara

Second, a parallel wave of protests swept across the Amhara region in mid-2016. As in Oromia, this was driven by land disputes and the resentment of Tigrayan domination within the EPRDF. Ethno-territorial sentiments in Amhara were heightened following the July 2016 arrest of Demeke Zewdu, a leading member of an organisation that opposed the 1995 allocation of the Welkait Tegede region to the Tigray regional state. The arrest of Zewdu, and of activist Nigist Yirga, precipitated a wave of protests in Amhara. A salient narrative among the Amhara presents the EPRDF’s system of ethnic federalism as a TPLF-dominated project aimed at subjugating the region. The grievances of the Amhara and Oromo, the two largest groups in Ethiopia, therefore converged to reject the TPLF-led federal government and, in the process, ushered Ahmed into power.10

Some leaders within the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP) initially saw the protests as an opportunity to loosen the TPLF’s grip on power. In early 2018, federal authorities released Asaminew Tsige – a man who was accused of plotting a coup against the EPRDF government in 2009 – among other political prisoners. Tsige took over leadership of the ADP – a move that indicated the party had morphed from being a TPLF client into a party that represents the growing nationalist sentiments in the Amhara region. On 22 June 2019, Amhara’s regional president and two other regional leaders were assassinated in the Amhara capital, Bahir Dar. In a separate attack in Addis Ababa, a bodyguard killed the military chief of staff, who hailed from Tigray. Federal authorities caught up with Tsige 36 hours later and shot him dead, then proceeded to arrest 260 people. Those arrested included a leader and dozens of members of the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA), an Amhara ethno-nationalist party established in June 2018.11

As the country gears up for elections in 2021, Amhara ethno-nationalists such as NaMA are positioning themselves against rivals in a regional government monopolised by the ADP and loyal to Ahmed’s Prosperity Party. In addition, Berhanu Nega’s Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (ECSJ) was formed in May 2019 from the merger of the Patriotic Ginbot 7 and many other parties. Amhara politicians will surely attempt to outbid one another in vilifying Tigray’s ruling elite during the electoral campaign. Meanwhile, tensions between Amhara and Oromo have been aggravated by the appointment of Tsige and the events following Hundessa’s assassination. In April 2020, Tsige’s successor in the ADP directed federal forces to move against Amhara nationalist community-defence militias, known as Fano, which had been part of the 2016–2018 protest movement. Amid the June 2020 protests, authorities arrested Eskinder Nega, an influential Amhara opposition leader with much support in Addis Ababa, who condemns Ahmed’s government as a front for a broader Oromo power grab.12

Tensions in Tigray

Third, tensions in Tigray relate to Ahmed’s moves to dismantle TPLF power structures, border disputes with the Amhara and the TPLF’s decision to go ahead with regional elections in September 2020. After assuming power in 1991, Ethiopia’s ruling EPRDF was dominated by the TPLF, a Marxist-Leninist and Tigrayan ethno-nationalist liberation movement founded in 1975. Given that Tigray was home to only 7% of the Ethiopian population and the TPLF had minimal support among Oromo and Amhara, Meles Zenawi’s government set about constructing a coalition of ethno-nationalist movements across the country’s nationalities. The four EPRDF members and the coalition’s associated ethno-national parties became the governing parties of the nine regional states, established from 1991 to 1995. This system of ethnic federalism aimed to weaken central control over the regions – but, in practice, the federal government’s influence and that of the TPLF remained strong throughout the 1990s and 2000s.13

Ahmed came to power in 2018 with the goal of dismantling the TPLF’s power within Ethiopian politics, in response to widespread sentiments that the TPLF was responsible for decades of repression and corruption. The reform agenda included releasing political prisoners, dismissing many senior TPLF figures from federal institutions and, in 2019, transforming the EPRDF coalition into Ahmed’s own Prosperity Party. Most notably, in June 2018, Ahmed replaced two of the most powerful TPLF figures: army chief of staff, Samora Yunis, and intelligence chief, Getachew Assefa. The prime minister’s April 2018 Cabinet reshuffle left the TPLF with only one ministerial position. Ahmed also replaced nearly every influential actor in the intelligence service, military and TPLF-associated economic complex. Leaders in Tigray accuse Ahmed’s government of applying selective justice by prosecuting high-profile members of their ethnic group for corruption and human rights abuses, but ignoring similar abuses committed by top officials from other regions.14

The TPLF’s waning power has energised long-held Amhara claims over Welkait and Raya, two territories in the Tigray region. Amhara leaders claim that the TPLF annexed these territories illegitimately in the 1990s and worked to alter the demographic makeup in favour of Tigrayans. The position of Tigrayan leaders is that the status of the two territories should be decided on the basis of a referendum that only current residents would have a say in. In December 2018, Ahmed set up a federal Administrative Boundaries and Identity Issues Commission to look into such territorial disputes. Fearing that the body will rule in Amhara’s favour, Tigray leaders argue that the commission is unconstitutional. These border disputes have sparked deadly proxy violence between the Amhara and the Qimant, a minority ethnic group that has been agitating for an autonomous zone within the Amhara regional state for a decade.15

Disregarding Parliament’s unilateral decision to postpone the national election due to COVID-19, Tigray went ahead with its own regional vote in September 2020. Leading up to the election, officials in Addis Ababa warned that following through on this decision may lead to conflict and would provoke diplomatic and economic punishment against the regional government in Tigray. After rejecting the merger into Ahmed’s Prosperity Party, the TPLF now stands as the only opposition bloc in the federal parliament. Some radical activists in Tigray back the idea of secession, though most TPLF veterans reject this course of action. With Amhara protesters having blocked all roads leading to Tigray since 2018, the TPLF has responded by bolstering its own security forces in Tigray. When the regional election was ultimately held on 9 September 2020, the TPLF received 98.2% of the vote and exited with 152 of the 190 seats in the regional parliament. The remaining 38 seats will be distributed among the four parties that participated in the election.16

Violence in the Somali Region

Fourth, violence escalated in the Somali region during the protests, including tensions between Oromo and ethnic Somalis along the disputed border between the two. The federal government used the Liyu police – a paramilitary controlled by the Somali regional state president, Abdi Iley – to quash dissent in Oromia. Initially formed to combat the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and Al-Shabaab, the Liyu police is one of the strongest and well-resourced regional forces. For their part, Oromo militias reportedly attacked Somali villages with the support of Oromia’s security forces. Violence erupted on 4 August 2018 in Jijiga and other parts of the Somali regional state following attempts by the Ethiopian army to dismantle the Liyu police and remove regional president Iley. Many locals accuse the Liyu police of human rights abuses, and the government views Iley as a pro-TPLF remnant. After Iley was forced to resign, some perceived his removal as an Oromo offensive against ethnic Somalis, leading to intercommunal violence.17

For decades, Addis Ababa’s relations with the Somali region, and Somalia, have been shaped by its conflict with the ONLF – a Somali separatist movement formed in 1984. The ONLF signed a peace deal with Ahmed’s government on 8 October 2018 and officially disarmed itself on 8 February 2019, based on an agreement with the regional government to reintegrate its members into the regional security forces. In September 2018, the ONLF indicated that it might push for a referendum on self-determination. The 2018 peace deal suggests that Ahmed’s government is more willing than the EPRDF to have a dialogue on this issue. The ONLF will be a strong contender in the upcoming elections with the Somali Democratic Party (SDP), which is now part of Ahmed’s Prosperity Party. The dilemma Ahmed faces in the Somali region is therefore “to curb the power of regional strongmen – whose behaviour is often a source of local grievance – without provoking an ethno-nationalist backlash, driven in part by perceptions… of Oromo chauvinism”.18

Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State Autonomy

Fifth, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State (SNNPR) is home to 45 indigenous groups and was previously ruled within the EPRDF by the fragmented Southern Ethiopia People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM). The Sidama and other ethnic groups seized on the opening caused by the EPRDF’s incoherence to press for their constitutional right to hold a referendum on establishing their own regional state. In July 2019, after months of neglecting the issue, federal authorities missed the deadline to hold the vote, causing Sidama protesters to clash with police and attack minorities. Voting eventually took place on 20 November 2019 and went off peacefully, with the Sidama opting resoundingly in favour of statehood. The Sidama are among a number of groups in the southern region whose aspirations for self-rule and greater autonomy have acquired momentum. Including the Sidama, who have already secured their statehood, 13 zones in the SNNPR have requested to become regional states.19

Egypt and the Dam Construction

Sixth, external forces also threaten Ethiopia’s fragile transition to democracy. Most notably, relations with Egypt are strained by the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia seeks to use the Blue Nile, a tributary that produces 85% of the Nile’s water flow, to accelerate its economic development. To protect its interests in the Nile water supply, Egypt has allegedly provided support to armed opposition groups in Ethiopia, particularly the OLF, ONLF and Ginbot 7. Sudan has been ambivalent, because the country stands to gain from the dam’s cheap hydropower and flow regulation, but worries about safety issues. The United States (US), European Union and South Africa, in its capacity as African Union (AU) chair, have been observing the talks between Ethiopia and Egypt. Consensus has been reached as to how Ethiopia should fill and operate the dam when there is sufficient rainfall, but outstanding issues include drought mitigation protocols and a dispute resolution mechanism.20

Negotiations reached a low point in February 2020, when officials in Addis Ababa claimed that the proposed deal would perpetuate Egypt’s unfair claimed quota of the Nile water and would commit it to drain the dam’s reservoir to unacceptably low levels in the event of a prolonged drought. Officials from Cairo and Washington, DC argued that Addis Ababa would be in breach of its international legal obligations if it were to begin capturing water in the GERD’s reservoir without a deal. In April 2020, Ahmed proposed an interim agreement to cover the first two years of filling the GERD’s reservoir – a piecemeal approach that Egypt rejected. Ethiopia reportedly began filling the reservoir months later, without having first signed an agreement on water flow. This report, which officials in Addis Ababa denied, came two days after the AU-brokered talks over the GERD failed to reach a deal on the pace of filling the reservoir. Officials in Cairo have threatened to take military action against Ethiopia in response.21

Volatile Relations with Eritrea

Finally, Ethiopia’s transition to democracy is conditioned by its volatile foreign relations with Eritrea. The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), formed in 1961, strategically allied with the TPLF during the final decades of its struggle to overthrow the former Derg regime and succeeded in gaining Eritrean independence in 1993. Relations deteriorated and the two countries went to war from 1998 to 2000, resulting in an estimated 70 000–100 000 deaths.22 The official reason for the conflict was a dispute over the border region of Badme, but this was merely a pretext for more complex political, social and economic issues. A peace treaty in Algiers established the Ethiopian-Eritrean Boundary Commission (EEBC), which ultimately ruled in favour of Eritrea on the issue of Badme and was subsequently rejected by Ethiopia. Mutual hostility was fuelled by Eritrea’s support of the ONLF against Ethiopia and EPRDF support of Eritrea’s opposition groups. In 2006, Ethiopia invaded Somalia in collaboration with the US and defeated the Islamic Courts Union – a move that drew Eritrea into Somalia.23

Thereafter, confrontational language, military build-ups and border skirmishes were a common occurrence. After the new administration in Ethiopia decided to implement the Algiers Agreement, Ahmed conducted a historic visit to Asmara on 9 July 2018 to re-establish diplomatic ties between Addis Ababa and Asmara. The two countries are united by their common interests in peace and economic development, as well as against the TPLF old guard that has dominated Ethiopian politics since 1991. Tensions among the TPLF, federal authorities and Amhara have been sharpened by Ahmed’s diplomatic outreach to Eritrean president, Isaias Afwerki. The rapprochement has since stalled, as the necessary steps stipulated in the Algiers Agreement (such as demilitarising border areas) have yet to be implemented. The border was initially opened following the peace accord, but was closed once again by the end of 2018. Afwerki cited the need to regulate trade and immigration, but also reportedly aimed to suffocate the Tigrayan economy.24

Conclusion

Since coming to power in 2018, Ahmed has been forced to manage a number of flashpoints. Internally, the Oromia, Amhara, Tigray, Somali and SNNPR regions each present their own set of challenges, which are difficult for Ahmed to reconcile simultaneously. Efforts to please one group often exacerbate tensions in another region. Externally, the main threats to Ethiopia’s stability are Egypt and Eritrea. In the lead-up to Ethiopia’s national election, now slated for 2021, foreign powers may exploit pre-existing regional tensions. Ahmed’s early moves to democratise softened the state, decreased the incoming regime’s ability to impose its will and empowered destabilising forces in the opposition, leading to widespread ethnic violence. However, the resort to state repression has equally been met by heightened waves of protests and unrest. This dilemma highlights the precarious standing of any regime attempting to transition towards democracy in a multi-ethnic state that is defined by relatively weak institutions.

Endnotes

- Field research for this project was undertaken during three lengthy trips to Ethiopia, totalling 18 months, from 2014 to 2019. While researching the South Sudan peace process, the author also developed close knowledge of the evolving political situation in Ethiopia.

- The “Master Plan” refers to an EPRDF pronouncement in 2014 that the area of the capital, Addis Ababa – which is a charter city that resides geographically within the southern-central region of Oromia – would be expanded by 1.1 million hectares of land. Many Oromo people viewed this plan as a ploy by the Amhara and Tigray to usurp fertile lands from the Oromo inhabitants of the region. The announcement of this expansion plan sparked widespread unrest in the capital and in Oromia, ultimately leading to its cancellation. See: Gammachu, Biraanu (2014) ‘Ethiopia’s “Master Plan” – Good for Development, Damaging for Minorities’, Available at: <minorityrights.org/2014/08/12/ethiopias-master-plan-good-for-development-damaging-for-minorities-2/> [Accessed May 1, 2020].

- International Crisis Group (ICG) (2019a) Keeping Ethiopia’s Transition on the Rails. ICG Africa Report No. 283, pp. 1–33.

- Aljazeera (2016) ‘Release of 10,000 Detainees Announced’, Available at: <aljazeera.com/news/2016/12/release-10000-detainees-announced-161221151521604.html> [Accessed 12 September 2020].

- ICG (2019b) Managing Ethiopia’s Unsettled Transition. ICG Africa Report No. 269, pp. 1–51.

- Ostebo, Terje (2020) ‘Analysis: The Role of the Qeeroo in Future Oromo Politics,’ Available at: <https://addisstandard.com/analysis-the-role-of-the-qeerroo-in-future-oromo-politics/> [Accessed 12 September 2020].

- ICG (2020a) ‘Defusing Ethiopia’s Latest Crisis’, Available at: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/defusing-ethiopias-latest-perilous-crisis> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- Ndiaye, Michelle et al. (2020) Peace and Security Report: Ethiopia Conflict Insight, Institute for Peace and Security Studies, 1, p. 8.

- ICG (2019a) op. cit.

- Fisher, Jonathan and Gebrewahd, Meressa Tsehaye (2019) Game Over? Abiy Ahmed, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front and Ethiopia’s Political Crisis. African Affairs, 118 (470), pp. 194–206.

- ICG (2020b) Bridging the Divide in Ethiopia’s North. Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 156, pp. 1–16.

- ICG (2019c) Preventing Further Conflict and Fragmentation in Ethiopia. ICG Commentary, pp. 1–5.

- Fisher, Jonathan and Gebrewahd, Meressa Tsehaye (2019) op. cit.

- Weber, Annette (2018) Abiy Superstar – Reformer or Revolutionary? Hope for Transformation in Ethiopia. SWP Comment, 2018/C, 26 July, pp. 1–4;

- ICG (2020b) op. cit.

- Ekubamichael, Medihane (2020) ‘TPLF Wins Regional Election by a Landslide’, Available at: https://addisstandard.com/news-tplf-wins-regional-election-by-landslide/ [Accessed 10 August 2020].

- ICG (2019b) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Ndiaye, Michelle et al. (2020) op. cit., p. 12.

- ICG (2020c) Nile Dam Talks: A Short Window to Embrace Compromise. ICG Statement, pp. 1–7.

- Gebre, Samuel (2020) ‘Conflicting Reports Issued over Ethiopia Filling Mega-Dam’, Available at: <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-15/ethiopia-starts-filling-nile-dam-at-center-of-dispute-with-egypt?sref=SCKvL4TY&cmpid%3D=socialflow-twitter-africa&utm_content=africa&utm_campaign=socialflow-organic&utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social> [Accessed 3 August 2020].

- Bezabih, Ferede Wuhibegezer (2014) Fundamental Consequences of the Ethio-Eritrean War [1998-2000]. Journal of Conflictology, 5 (2), p. 42.

- Matshanda, Namhla Thando (2020) Ethiopian Reforms and the Resolution of Uncertainty in the Horn of Africa State System. South African Journal of International Affairs, 27 (1), pp. 25–42.

- Ylonen, Aleksi (2019) From Demonisation to Rapprochement: Abiy Ahmed’s Early Reforms and Implications of the Coming Together of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Global Change, Peace and Security, 31 (3), pp. 341–349.