Introduction

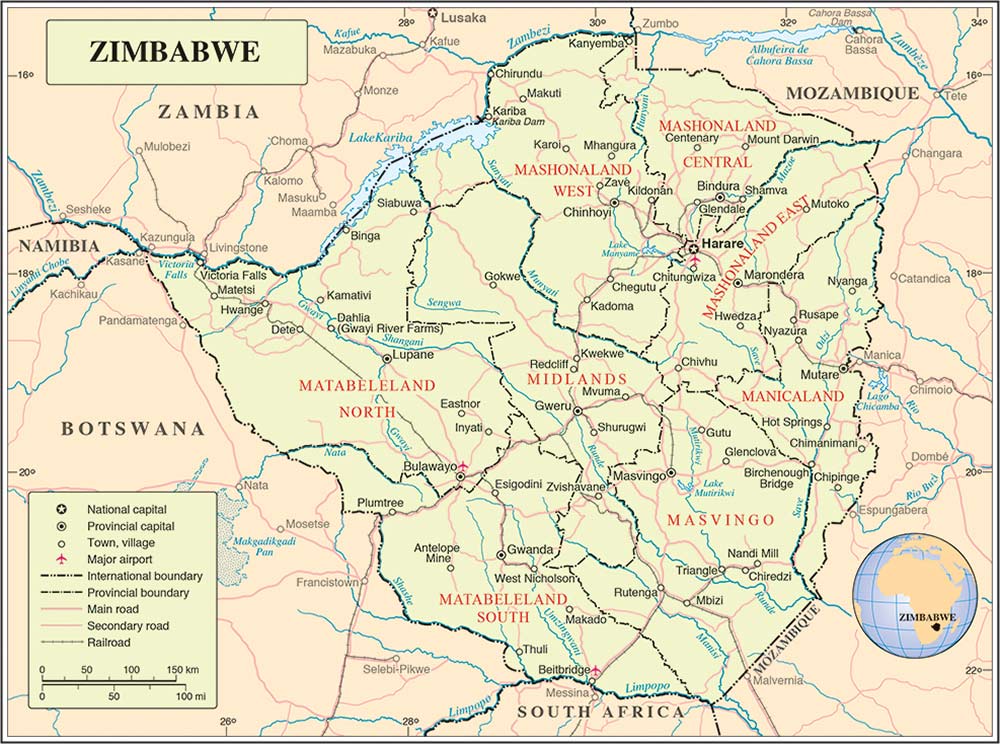

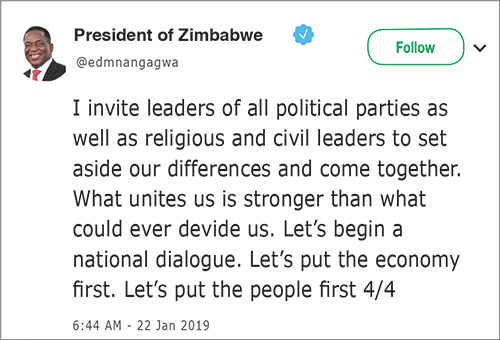

Beyond offensive international diplomatic actions, court applications and protests, a national dialogue appears the best alternative to resolve Zimbabwe’s swelling socio-economic and political afflictions. The country is at a crossroads as its political and economic crises deepen. To salvage it from complete collapse, President Emmerson Mnangagwa, on 22 January 2019, called on political parties, churches and civic society leaders to participate in a national dialogue. Only political parties, however, were invited to the inaugural dialogue, which commenced on 7 February 2019. Churches, on the other hand, have mooted their own national dialogue process. The dominant purpose of both dialogue initiatives, however, remains vague to ordinary citizens and to diverse stakeholders, yet the principle of inclusivity should underpin such developments. This article therefore provides insights on what constitutes a national dialogue, why it is necessary, the potential for success, challenges, and possible steps towards an inclusive process.

The call for dialogue followed an intensified political crisis triggered by fuel price hikes, leading to countrywide protests from 14 to 16 January 2019. The protests were met with repression and heavy-handedness by state security agents. The Human Rights Non-governmental Organisation (NGO) Forum “recorded at least 844 human rights violations during the shutdown. Consolidated statistics so far reveals the following violations: killings (at least 12); injuries from gunshots (at least 78), assault, torture, inhumane and degrading treatment including dog bites (at least 242), destruction of property including vandalism and looting (at least 46), arbitrary arrests and detentions (466), and displacements (under verification).”1 The Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU)-initiated protests attracted serious state repression after being hijacked by criminal elements, who took advantage of the protests. This led to the destruction of hundreds of properties, with businesses losing about US$300 million during the protests in question.2

The government’s reaction to the January 2019 protests is analogous to the 31 July 2018 incidences. On 31 July 2018, opposition political activists took to the streets in Harare to protest against delayed election results. In an attempt to address the consequences of the protests and shootings that took place, Mnangagwa established a Commission of Inquiry, led by the former president of South Africa, Kgalema Motlanthe. The Motlanthe Commission report stated that “the deaths of six people and the injuries sustained by 35 others arose from the actions of the military and the police”.3 The commission also described the protests in these words: “[T]hey were pre-planned and well-orchestrated as evidenced by the arrival time of the protesters and the material that they brought along which included posters, bricks, stones and containers among others.”4

In line with the current call for national dialogue, the 1 August 2018 Commission of Inquiry recommended the “establishment of multi-party reconciliation initiatives, including youth representatives, national and international mediators to address the root causes of the post-election violence and to identify the implementing strategies for reducing tensions, promoting common understanding of political campaigning, combating criminality and uplifting communities”.5 It is within this context that the call for a national dialogue should be heeded and be considered as an urgent matter for Zimbabwe.

What is National Dialogue?

National dialogues are a peacebuilding mechanism that can be used to bring together diverse stakeholders (state and non-state actors) when political institutions and governance systems have essentially collapsed, been delegitimised or when the survival of a government in power is in question.6 National dialogues (sometimes called national conferences) may also be defined as broad-based, inclusive and participatory negotiation platforms involving large segments of civil society, politicians, youth, women, academia and peacebuilding experts. They are ordinarily convened to negotiate major political reforms or peace in complex and fragmented conflict environments.7 These dialogues usually happen in contexts where there is high socio-economic and political conflict beyond the containment of traditional security institutions, such as the police and military institutions. In practice, national dialogue processes may last for long periods, depending on the complexity of issues being addressed and the attitudes of actors involved.

National dialogues are highly contextual and their objectives are customised to the conflict-affected country or society. For example, South Sudan, as a conflict society, has its 10-point national dialogue8 objectives: (1) ending all forms of violence; (2) redefining and re-establishing stronger national unity; (3) strengthening the social contract between citizens and the state; (4) addressing issues of diversity; (5) agreeing on a mechanism for allocating and sharing resources; (6) settling historical disputes and sources of conflict among communities; (7) setting the stage for an integrated and inclusive national development strategy and economic recovery; (8) agreeing on steps and guarantees to ensure safe, free, fair and peaceful elections and post-transition in 2019; (9) agreeing on a modality for a speedier and safe return of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees; and (10) furthering national healing, peace and reconciliation. This indicates that national dialogues can be primarily an instrument for sustainable political transitions and peacebuilding beyond the maintenance of law and order by state security institutions. National dialogue objectives are dependent on whether the dialogue is formal or informal. Informal national dialogues are non-commissioned processes, usually commenced by non-state actors such as churches and civil society, while formal dialogues are sanctioned by government mandates and could produce binding resolutions for participating actors. Informal national dialogues, however, usually result in formal processes that could affect political and constitutional reforms. In the current Zimbabwe context, the Zimbabwe Council of Churches (ZCC) has commenced informal national dialogues, while Mnangagwa has commenced the formal national dialogue processes.

The National Dialogue Process

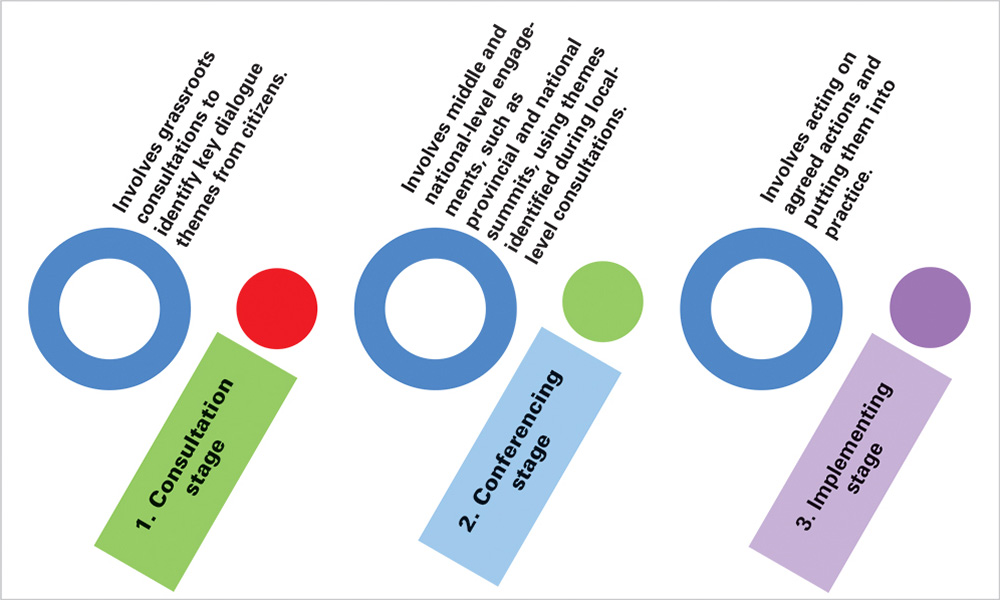

Ideally, national dialogues should involve both local and national stakeholders to gain legitimacy and to truly reflect the national character. The process must be inclusive throughout its entire life and participation should involve wider constituencies. Figure 1 illustrates a typical dialogue process involving three stages: the consultation stage, conferencing stage and implementation stage.

Consultations involve gathering local citizens’ views on what should constitute the national dialogue, with the objective of identifying key dialogue issues. This stage sets the agenda for national dialogue. Generally, focus group discussions and interviews from diverse socio-economic and political groups are carried out as part of the consultation processes. The Zimbabwean national dialogue missed this stage, as both Mnangagwa and Nelson Chamisa, leader of the main opposition party in Zimbabwe, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance, have conceptualised national dialogue within the context of disputed elections and interparty dialogue. No community-level consultations were undertaken to establish a grassroots-informed national dialogue framework. Inclusive dialogues (consultations) promote public support and enhance bottom-up buy-in from diverse sectors.

Conferencing involves middle-level engagements at the regional and national levels. The conferencing processes are meant to refine issues gathered from grassroots consultations and to develop possible policy options and implementation mechanisms. The Zimbabwean national dialogue could still meet this stage’s expectations by facilitating provincial- and district-level dialogues that include diverse stakeholders, rather than political parties only.

Implementation involves putting into action the agreed plan, with political will being the key ingredient. When implementing agreed positions from a national dialogue, it is pertinent to adhere to implementation mechanisms. Such implementation mechanisms may include the establishment of an implementation committee, the development of an implementation timetable and expected deliverables, trust-building measures and commitment regulations.

Reflections on Zimbabwe’s National Dialogue Design

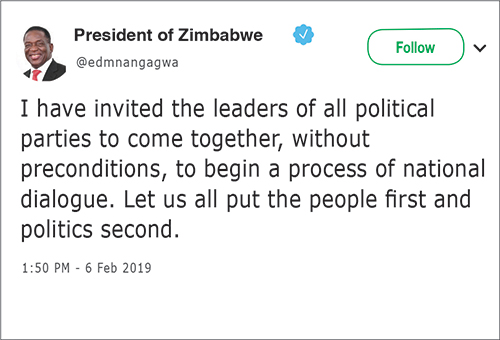

Zimbabwe’s attempts to facilitate a national dialogue have begun with both high hopes and low expectations. Following countrywide protests and their subsequent repression by state security agents led by the defence force, the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC) initiated a national dialogue process. It began with meeting diverse stakeholders “to create space for national conversations aimed at achieving social, economic and political transformation”.9 The NPRC’s initiative sought to establish a framework for national dialogue. However, the government of Zimbabwe mooted its own national dialogue initiative, with the interparty meeting held on 6 February 2019 at the president’s residence. The dialogue brought together nearly 22 heads of political parties who contested the 2018 elections.

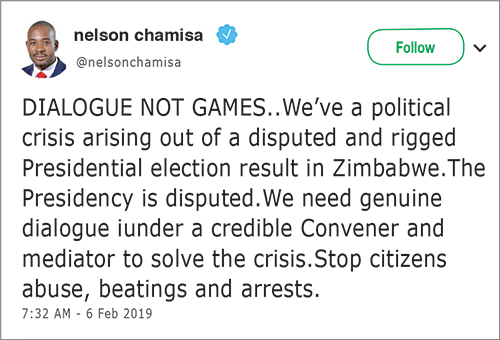

President of the MDC Alliance, Nelson Chamisa, however, snubbed the dialogue, citing the inappropriateness of the venue, the legitimacy of Mnangagwa as the convener and the dialogue’s biases towards elections. Among the opposition parties that attended, some labelled their counterparts as cheerleaders “walking the government’s talk” while a few demanded the tabling of various development issues, including identifying ways to address the deepening economic crisis, an end to human rights abuses, electoral reforms and a return to the rule of law.

Churches, through the ZCC, have also started a national dialogue by facilitating all stakeholders’ meetings. The ZCC has already facilitated a broad-based dialogue bringing together political elites, civil society, churches and business leaders to start a conversation focused on nation-building. In addition, the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace has been making efforts to facilitate a national dialogue. Parallel national dialogue efforts by the church bodies require harmonisation to harness efficiency, effectiveness and full impact. However, the churches’ dialogue is an informal national dialogue process that feeds into the government’s national dialogue initiative.

What is peculiar about all the dialogue platforms being conceptualised by the NPRC, the president of Zimbabwe and the opposition MDC Alliance is that they seem convoluted. The key stakeholders have different dialogue starting points, and different objectives and agendas. While Mnangagwa called for a post-election dialogue, the MDC Alliance anticipated a dialogue that includes discussions around the legitimacy of the presidency, the constitution and the economic crisis, among other issues. The NPRC, on the other hand, commenced the national dialogue with a semi-broad-based consultative process aimed at establishing a framework for national dialogue. The NPRC’s initiative seems globally inclusive and holistic:

“In an effort to come up with a framework for national dialogue, conversations were centred around the following key questions; why are Zimbabweans not talking? What are the key pillars of national dialogue? Who should participate, how and at what level? How should a dialogue process be structured? What does a successful dialogue look like?”10

The NPRC’s entry point to the dialogue had neither preconditions nor positions, as is the case with the ruling party Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the MDC Alliance. However, the NPRC aborted its initiative when Mnangagwa asked the commission’s chairperson to facilitate his national dialogue meeting. Justifying his decision, Mnangagwa said: “I had invited an unnamed cleric to chair this meeting, who then became an activist, so I had to drop him and engaged retired Justice Selo Nare.”11 This change of roles by the NPRC chairperson removed his independence as well as trust in the commission’s initial process.

Some of the specific reflections characterising Zimbabwe’s national dialogue process include:

Inclusive participation: The national dialogue discourse has missed key factors for a participatory process that involves different social groups and sectors. Demanding inclusive participation, the Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition argued that “the national dialogue process must never be restricted to political parties but should rather bring on board a cross section of stakeholders that include civic society, labour, women, youth, persons living with disabilities, farmers, media, students, the diaspora, religious groups and business among other critical stakeholders [sic].”12 Public support is central to any successful national dialogue, and without it the process may suffer a crisis of legitimacy. Hence, the government may need to formally promote inclusive processes that solicit views from diverse socio-economic and political structures.

Scope: The government’s national dialogue facilitation conceptualised the Zimbabwean crises in the context of post-election negotiation, rather than a popular national crisis requiring broad-based consultative content. While the government of Zimbabwe called for interparty dialogues based on the 2018 election conflict, urgent national issues requiring redress include the economic crisis, unemployment, constitutional reforms and continuing human rights violations. More broadly, there is lack of clarity on the mandate of the national dialogue designed, hence the need to spell out what this intended dialogue seeks to achieve.

Regional and national-level consultations: Following local-level consultations, regional and national consultation summits should be conducted to solidify the grassroots views towards specific policy directions. However, it seems that these are less likely to occur given that the dialogues commenced with an electoral political agenda, as opposed to a public agenda.

Preconditions: Political parties and civil society organisations have already listed preconditions that should be considered by Mnangagwa and his party before participating in the national dialogue process. For example, the MDC Alliance argued that to participate in the national dialogue, “the dialogue must be convened by an independent mediator and not one of the disputants (President Mnangagwa),” and that a genuine dialogue can only be mediated by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union or the United Nations.13 Putting forward such preconditions before the initial meeting to set out the dialogue framework makes it difficult to establish a common ground for dialogue.

Political will: The high levels of mistrust among rival political groups could hinder positive political will, which would affect the implementation of the dialogue resolutions. For example, if some of the parties involved in the national dialogue negotiate in bad faith or fail to collaborate with others on agreed positions, there is a likelihood of jeopardising the success of the national dialogue.

Facilitators: The current Zimbabwe government-supported national dialogue is being facilitated by the Office of the President and Cabinet. Their convening credibility could be compromised, given that the president is a stakeholder in the national dialogue process. The opposition leaders have already raised this, while demanding mediation by SADC or any other respected people. Facilitators are typically people with a high degree of political legitimacy in the country or internationally. However, given Zimbabwe’s current political context, the success rate of the national dialogue depends on Mnangagwa as the facilitator-participant in the process.

Recommendations for an Effective National Dialogue Design

Mandate of the national dialogue: National dialogues must have formal mandates. As such, the scope and goal of the national dialogue must be specified and have all Zimbabweans in support of its objectives.

The national dialogue must reflect a “national character” rather than contexts that do not mirror national problems affecting the country. While the current scope of the national dialogue is confined to post-election processes, a broader socio-economic and political focus is necessary.

Inclusivity: There is need to develop a genuine national dialogue framework that involves people at the grassroots to shape the national discourse. Grassroots consultations can involve countrywide public meetings and think tank forums, where citizens will have an opportunity to air their views about what should constitute national dialogue.

Preconditions: All stakeholders – including the ruling party, the opposition parties, churches and civil society members – must not engage in the dialogue with antagonistic preconditions that potentially affect progressive engagement. There is a need for all parties involved in the national dialogue to approach it with an open mind and establish terms of reference that are agreeable to all parties.

Transparency: The government must establish transparent dialogue platforms and processes with fair representation of different sections of Zimbabwean society. This can be accomplished by ensuring there are clear communication channels that relay information to the parties involved in the dialogue process, as well as to the citizens.

Halting continuing human rights violations: It is of paramount importance for the government to work effectively towards creating an enabling environment that shows sincerity and instils trust among participating stakeholders. As such, halting continuing human rights violations could improve the opposition and non-state actors’ willingness to participate in the national dialogue process.

Defined realistic issues: It is essential that the national dialogue objectives be realistic and be determined in a consultative and inclusive manner. This means there has to be a consensus-driven agenda that is manageable, achievable and definable.

Women’s participation: Pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325, adopted in 2000, it is important to deliberately include women in national dialogue processes. The inclusion and involvement of women in designing and implementing the national dialogue process enhances gendered processes.

Implementation mechanisms: There is a need to develop specific implementation time frames and monitoring mechanisms. A time-framed dialogue process improves efficiency and effective engagements, as well as enhanced resource management.

Constitutional mechanisms operationalised: To complement the national dialogue processes, the government should commit itself to the rule of law by ensuring that the judiciary executes its duties without the interference of the executive. Violating the constitution could erode trust among parties in the national dialogue. For example, after calling for the national dialogue, Mnangagwa threatened to use violence against citizens who might protest against bad governance. As a result, some political parties that were participating in the national dialogue pulled out, citing the president’s insincerity.14

Conclusion

For Zimbabwe, Mnangagwa’s call for national dialogue is a positive step towards transforming the country’s socio-economic and political crises. However, the national dialogue’s design has missed crucial steps, which include grassroots consultations and inclusive participation. The national dialogue process only involves political parties, yet there is the need to include civil society, women, youth and peacebuilding experts. As discussed previously, the national dialogue process must have a clear mandate, and be transparent and inclusive. The parties involved in the national dialogue must approach the process with an open mind, without preconditions and establish implementation mechanisms that guarantee its success.

Endnotes

- Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (2019) ‘On the Days of Darkness in Zimbabwe’, Kubatana.net, 18 January,

Available at: <http://kubatana.net/2019/01/18/days-darkness-zimbabwe/> [Accessed 15 February 2019]. - Share, Felex (2019) ‘Cabinet Sets up Team to Assess Demo Damage’, The Herald, 30 January, Available at: <https://www.herald.co.zw/cabinet-sets-up-team-to-assess-demo-damage/> [Accessed 17 February 2019].

- Madhomu, Tendayi (2018) ‘Motlanthe Commission Issues Verdict’, The Daily News, 20 December, Available at:

<https://www.dailynews.co.zw/articles/2018/12/20/motlanthe-commission-issues-verdict> [Accessed 16 February 2019]. - Government of Zimbabwe (2018) Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the 1st of August 2018 Post-election Violence.

Harare: Government of Zimbabwe, p. VI. - Ibid., p. 53.

- IPTI (2017) What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues. Briefing Note’, Available at: <https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/IPTI-Report-What-Makes-Breaks-National-Dialogues.pdf> [Accessed 4 February 2019].

- Paffenholz, Thania and Ross, Nick (2016) Inclusive Political Settlements: New Insights from Yemen’s National Dialogue. Geneva: The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

- Gurtong Trust (2017) ‘South Sudan National Dialogue Steering Committee Document Number One October 2017’, Available at: <http://www.gurtong.net/Portals/0/October-2017-South-Sudan-National-Dialogue.pdf> [Accessed 6 February 2019].

- Razemba, Freeman (2018) ‘NPRC Initiates National Dialogue’, The Herald, 1 February, Available at: <https://www.herald.co.zw/nprc-initiates-national-dialogue/> [Accessed 16 February 2019].

- Ibid.

- The Zimbabwe Mail (2019) ‘It’s Chamisa’s Democratic Right to Snub Dialogue – Mnangagwa’, Available at: <https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/zimbabwe/its-chamisas-democratic-right-to-snub-dialogue-mnangagwa/> [Accessed 8 March 2019].

- The Zimbabwean (2019) ‘Zimbabwe’s National Dialogue Must Never be Restricted to Political Parties’, Available at: <https://www.thezimbabwean.co/2019/02/zimbabwes-national-dialogue-must-never-be-restricted-to-political-parties/> [Accessed 8 March 2019].

- Zvinonzwa, Eddie (2018) ‘Honesty, Mutual Respect Key to National Dialogue’, The Daily News, 7 February, Available at: <https://www.dailynews.co.zw/articles/2019/02/07/honesty-mutual-respect-key-to-national-dialogue> [Accessed 7 March 2019].

- Zimbabwe Situation (2018) ‘More Parties Pull Out of ED Talks’, 26 February, Available at: <https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/more-parties-pull-out-of-ed-talks/> [Accessed 8 March 2019].