Introduction

The drive for survival and for greener pastures has continued to force millions of West African young men and women to gamble with death in attempts to cross over to Europe and other parts of the world. This quest to escape poverty, hunger, unemployment and insecurity, among other reasons, caused a major segment of Nigeria’s population to seek alternatives for better livelihood prospects for themselves and their families.1

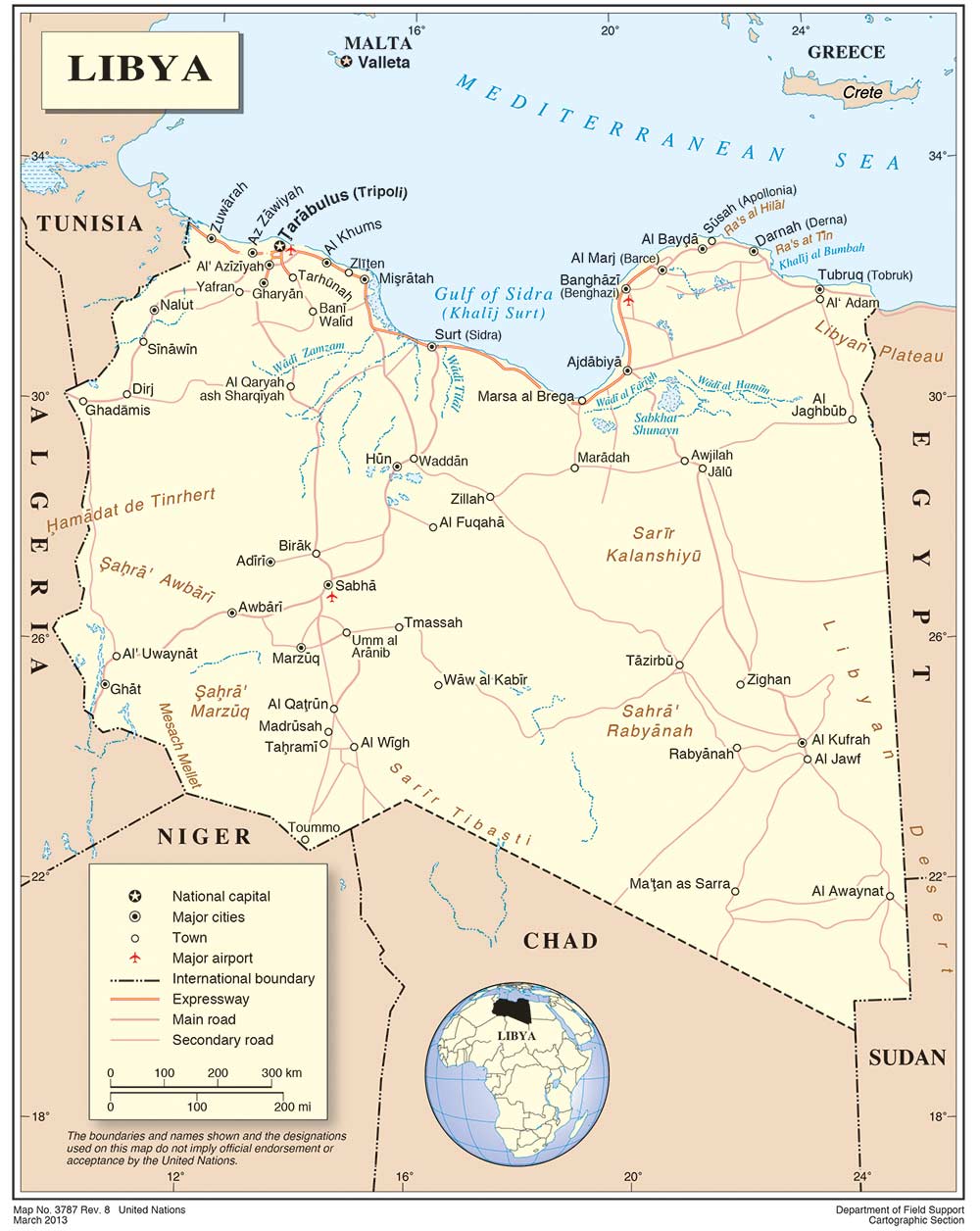

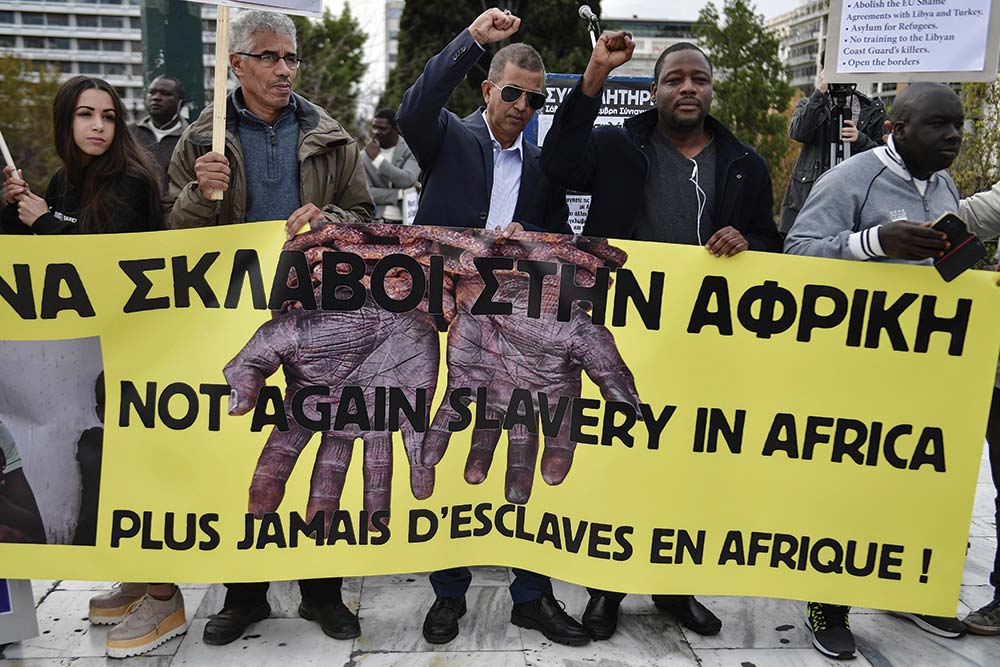

Those seeking economic survival see irregular migration as the best alternative, given the difficulty and resources involved in migrating through regular and legitimate routes. In many instances, very few of the original number who set out on these dangerous journeys live to tell their stories. While many regularly drown in the Mediterranean Sea, many also die in the deserts, and others are sold as slaves in a modern slave market. Most of the victims of this trade are from West Africa. Many of them leave home with expectations of getting to Europe and other destinations perceived to have better economic prospects for them, but they end up in the slave merchant nets in North Africa. The victims are put in camps and sold in open markets in Libya, while the international community watches in silence. The geographical location of Libya renders it a transit route for migrants journeying to Italy and many other parts of Europe. The migration crisis in Libya and its attendant consequences was made more possible by the instability in Libya, occasioned by the October 2011 North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO)-led war against Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. The fall of that regime left the country even more politically unstable, with increased security threats that are spilling over into other parts of Africa. Europe, in particular, lost a credible partner in its efforts to address or reduce irregular migration from Africa. Poor governance and institutional ruin as a fall-out of the war paved the way for the emergence of criminal syndicates, whose trade in human beings is now finally attracting some global attention. To address this, the European Union (EU) proposed setting up reception centres in Libya for African migrants while their asylum applications undergo consideration.

This was rejected by the Libyan government, resulting in the migration crisis, with many splinter militia groups participating in the apparently lucrative slave business.

The combination of all these factors places Libya and other North African countries at the forefront of the migration crisis, both as victims and as perpetrators. Trafficked Africans transiting through Libya face insecurity, extortion and inhumane treatment meted out by their slave masters. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) supported this claim in its report.2 It suggests that the trade in human beings, mostly of West African descent, has become like every other regular business where people are being traded in public like goods, as was the case during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

This article interrogates the underlying factors leading to the crisis, with emphasis on the resurgence of the slave trade in Libya. It examines the experience of Nigerians, who are victims of the crisis. It begins by unpacking migration in Nigeria, followed by an examination of the enablers and triggers of the crisis. The article then looks at the national, regional, subregional and global responses to the crisis while suggesting a way forward for Nigeria, Africa and the world.

Migration from Nigeria

The discovery and exploration of oil in the 1970s made Nigeria the biggest producer of crude oil in West Africa and the sixth-largest supplier of oil in the world.3 Oil revenue became significant to Nigeria’s emergence as a global player in world politics. The oil wealth also made Nigeria a destination for foreigners, especially expatriates who came into the country for business or professional engagements. However, the effect of diminishing oil revenue became more pronounced for Nigeria from the 1980s; this also meant diminishing national income. As a consequence, the nation’s global influence also began to diminish. The result of this was a change in demography as more people began to emigrate.

Historically, Nigeria’s migration crisis and the quest to leave the country in search of better prospects began with the economic policies of the 1980s, which caused much hardship for people. The Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) that was meant to heal the country of its debt-induced development crisis ended up complicating the country’s economic woes, leading to unimaginable hardships with associated unemployment, poverty and corruption. This resulted in large numbers of young men and women seeking better livelihoods abroad. Alemika contends that in the 1980s and 1990s, the SAP destroyed the economy and any social progress made in the country after independence from colonial rule.4 Many of the SAP policies led to government downsizing or a withdrawal of social services, thereby creating a huge population of deprived and excluded citizens.5 Consequently, many of these deprived and excluded citizens, whose conditions became more complicated, took to crime, while others began to migrate out of the country by any means – a situation that has continued, even in the face of a government crackdown.6

Irregular Migration: A Growing Challenge

Irregular migrants fall into two categories: those who enter destination countries legally and overstay their visas, and those who leave Nigeria without proper travel documentation and/or enter destination countries illegally. Migrants who enter through unofficial routes fall under the definition of irregular immigrants.

Irregular migration occurs both out of and into Nigeria. Citizens within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) overstay their 90 days of grace without regularising their stay – hence, the major expulsion exercises of January–March 1985 and May–June 1986.7 Those who overstay their visit to the country do not only come from the ECOWAS region – occasional expulsions of many expatriates in the commercial, professional and oil sectors of the economy have also taken place. These people either overstayed their visa period or entered without the necessary documents to be able to stay.

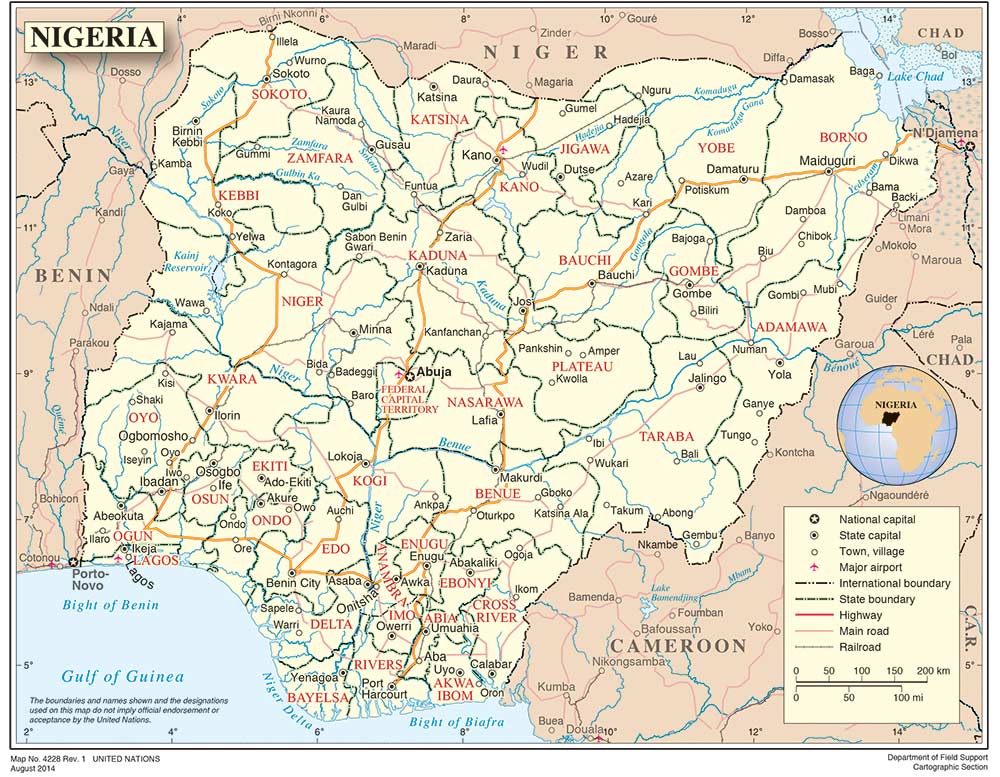

According to a survey by the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons and other Related Matters,8 the major trafficking routes from Nigeria are in Edo, Kano, Kaduna, Sokoto, Katsina, Kebbi, Jigawa, Yobe, Borno, Calabar and Lagos, and from border areas around Benin, Cameroon, Gabon, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso and Mali. Nigerians have been emigrating, despite the associated risks. The total number of Nigerians living outside the country cannot be easily determined, because of the irregular pattern of their movements. A huge number of people travel without official documents, both at home and in the host countries.9 Most of these migrants are subjected to inhumane treatment, which they have to endure because of their inability to obtain official documents permitting them to live and do business in their host country, while many are repatriated once they are caught. The circumstances of their departure – such as using unofficial routes and without proper documentation – have made them vulnerable to criminal gangs. These gangs recruit them into all manner of illicit businesses, with long jail sentences as consequences when they get caught.10 Many are trafficked to West, North and Central African countries, and to Europe and the Middle East – especially to Benin, Cameroon, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Niger, Libya, Italy, Greece, Spain and Saudi Arabia, among others – for forced labour. Most of the trafficked women in Europe are believed to be from Edo State, with Italy being the most frequent destination for trafficked persons from Nigeria.11

Policy Framework Governing Migration

Nigeria is one of the few countries in West Africa to have adopted a national policy on migration, with support from the IOM and EU. The policy and its implementation plan provide an appropriate legal framework for monitoring and regulating internal and international migration, and the proper collection and dissemination of migration data. The policy also addresses issues related to diaspora mobilisation, border management, the decent treatment of migrants, internally displaced persons (IDPs), asylum seekers and the role of civil society in migration management, to ensure more efficient management of migration in Nigeria.12

The policy is all-inclusive, covering migration and development, migration and cross-cutting social issues, national security and irregular movement, forced displacement, human rights issues, organised labour migration, internal migration, the national population, migration data and statistics, among other elements.

In addition, the policy proposes the establishment of an agency or commission to coordinate different management aspects of the migration policy. As a result, the National Commission for Refugees, Migrants and Internally Displaced Persons (NCRMI) statutorily became the focal agency on migration-related issues, in close coordination with other agencies implementing the policy.

There are identified gaps in the operations of various ministries and agencies with mandates related to migration issues functioning independently with little or no coordination. This situation sometimes leads to incoherence in terms of policy and planning. However, if the policy is fully implemented, the gaps in the area of coordination would be addressed, as the lead agency role is assigned to NCRMI.

Furthermore, the Act establishing institutions dealing with migration issues, such as the NCRMI, has not been reviewed to deal adequately with the migration crisis in terms of resources and human capacity.

Identifying the Key Drivers in the Libyan Migrant Crisis

Libya and its neighbours in the North African region are major exit points for West African migrants journeying to Europe. The illegal migrants prefer to travel via the Mediterranean Sea to avoid being caught by security operatives. It is important to note that the turning point in Libya – the overthrowing and death of Gaddafi – resulted in the sparsely populated country sliding into near anarchy, characterised by violence, chaos and a proliferation of small arms and light weapons in and out of the country.

This event, and the situation that followed, are central to the alleged criminal activities going on in Libya. The political and economic instability that ensued following the regime change in Libya had significant security implications. Gaddafi and his regime had been able to maintain a level of security while also controlling the activities of militias. However, since his exit, authorities in Libya have not been able to control the activities of these militias. It is these militias that control the human trafficking business in different parts of the country. Examples of trafficking centres exist in Gharyan and Zawiya, where many Nigerian returnees claim that they were detained, maltreated or sold for ransom.13

Another perspective on the crisis is what an African Independent Television report, titled “Addressing the Push and Pull Factors”, called an international conspiracy of silence and a global agreement to regulate migration.14 This report argued that as a matter of policy, many European countries have tightened their borders and incoming routes as measures to keep in check the influx of refugees in their territorial confines. In 2015, Italy raised the alarm that it had reached its peak in terms of receiving migrants. Supported by other European countries, the regulation of migration began to drive EU policies, and it became a key factor for elections and foreign policy.

Push and Pull Factors

Guggenheim and Cernea argue that anthropologists identify push and pull factors as the forces behind voluntary and forced migration.15 Push factors force people out of their traditional localities and are responsible for forced displacement and the refugee crisis. Pull factors attract people to migrate from their place of abode to a new area. A saturated labour market, demographic shifts, unemployment, poverty, extractive political and economic institutions and political crises are identified push factors.16 However, unless demographic growth is at the same pace with adequate economic growth, the lack of employment opportunities and economic survival in Nigeria will remain an important driver of irregular migration. In addition, the prospect of earning higher wages abroad adds to the attraction for migrants. The difference between voluntary and involuntary population movements is that the latter are caused by push factors, while the former is due to pull factors. Levels of anxiety and insecurity are therefore much higher among involuntary migrants. In Nigeria, many of the young men and women who seek to leave the country on a daily basis, in search of economic survival, fall into either the push or pull categories. Forced migration induced by push factors are a function of prolonged conflicts, such as the Niger-Delta crisis, the Boko Haram insurgency and election violence, among others. Better economic conditions and the search for better lives account for why Nigerians, and other Africans, continue to move en masse to other parts of the world, despite the associated negative consequences – including the modern slave trade to which West Africans are subjected to in Libya.

Response to the Migrant Trafficking Crisis

Global Response

The human trafficking of migrants in Libya provoked an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in 2017. A presidential statement condemning the slave trade of migrants in Libya was made on 7 December 2017.17 The UNSC is putting pressure on the UN-backed government in Libya to act accordingly to stem this crisis. As a result, the Libyan government promised to increase the number of flights repatriating stranded migrants while investigating the slave trade activities. Nigeria and other countries whose citizens are often victims of the trade have been engaging with the Libyan authorities in the repatriation of affected citizens. The big challenge, however, is how likely a near-failed state with the absence of necessary institutional frameworks can control this human trafficking trade.

Regional Response

At the 5th AU-EU Summit in Abidjan on 29-30 November 2017, AU chairperson, Alpha Conde, announced that the slavery auction was the unofficial but real theme of the summit. This came as a result of the disturbing news documentary presented by Cable Network News (CNN), titled “People for Sale: Exposing Migrant Slave Auction in Libya”.18 The official theme of the summit, “Investing in Youth for Accelerated Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Development”, was overshadowed by the Libyan crisis. Several meetings were held on the sidelines of the summit, involving the AU, EU, UN and the governments of Libya, France, Germany and others, to try and draft an appropriate response to the crisis.19 An emergency plan of three phases was drawn up. The first phase included the creation of a joint task force of police and intelligence forces of AU and EU countries, to dismantle the human trafficking network responsible for slavery and other human rights abuses of migrants in Libya, their financing, and to arrest traffickers. This would be in addition to the French proposed military action against the traffickers, which would reinforce police action against the criminal network.

The second part of the plan proposed by the summit in Abidjan was to launch an urgent operation to evacuate migrants from camps or detention centres in Libya and repatriate those who wanted to go home. There are about 3 800 migrants – mostly West African women and children – held under inhumane conditions in one out of over 40 identified camps, as acknowledged by Libyan authorities.20

The third part of the plan mapped out at the 5th AU-EU Summit was the establishment of an AU Commission of Inquiry into the root causes of the migration from African countries to Europe. In addition, the Commission was to map out alternative homegrown work engagements for African youth to discourage them from emigrating in search of better livelihoods. This could be achieved by focusing on infrastructure development on the continent. At the summit, the EU agreed to invest €4.3 billion into Africa in the first phase, and another €44 billion for the second phase. This is to be executed by EU companies through investment guarantees.21 How effective the three-phase emergency response plan or the long-range plan to tackle the root causes of the migrant crisis would be, will probably vary.

Subregional Response

As part of the reaction to the growing news of a modern slave business in Libya, vice president of the ECOWAS Commission, Edward Singhatey – who spoke on behalf of the president, Marcel Alain de Souza, on 29 November 2017 – expressed a clear warning that the subregion would not sit back and watch its citizens being bought and sold as slaves on the continent.22 The ECOWAS Commission launched an investigation into the alleged maltreatment and trading of West African citizens as slaves in North Africa. The global economic crisis that led many West African powers into recession, including Nigeria, has adversely affected ECOWAS’s assertive position and rapid response to events on the continent. While ECOWAS may currently be constrained to act and assist the affected states, it has engaged in multilateral support with the UN and other international organisations, such as IOM, to help in ending the perils of the migrants and speedily repatriate them.

National Response

In response to the harsh conditions that Nigerians are facing in Libya, the Nigerian government, through the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), began making arrangements to airlift 5 037 stranded Nigerians in Libya back to Nigeria.23 Those who have been repatriated to the country are currently being engaged by the government in various skills acquisition programmes, including shoe-making, tailoring and hairdressing, among others. The government is also making policies that will further protect Nigerian citizens, both at home and abroad. Beyond this, the government is empowering the youth economically, and this can go a long way in discouraging desperation and the need for the youth to go in search of better means of livelihood.

The Way Forward

The international community should agree on a single, comprehensive narrative that would label the criminality and bring an end to modern slavery, by developing policies and frameworks to tackle the root causes of the migration crisis.

The joint regional summit on the Libyan migrant crisis made laudable progress, but failed to admit the negative roles played by different actors. All parties to the crisis must accept responsibility for the situation so that the continent, and the world at large, can move forward.

The federal government of Nigeria should seek and foster stronger cooperation with neighbouring African countries, Europe and the entire international community to control illegal migration and end acts of criminality against migrants.

The EU should create an enabling environment for migration to fill the gap created by its ageing population, while African governments at national level should prioritise economic development through investment in the youth, as a panacea to curbing the migration crisis.

There is a need to remove complete restrictions of entry into European countries and open it up for more legal migration from Africa, to discourage African youth from embarking on deadly, illegal journeys.

Conclusion

The NATO-backed popular uprising against Gaddafi’s 42-year rule and the eventual overthrow of his regime created a major crisis in the country. Before his death, Gaddafi controlled the human trafficking networks, which now operate with little or no restrictions. The country is now fertile ground for a succession of transnational organised criminal activities, including human and arms trafficking. The number of West Africans journeying to Europe through North Africa to escape domestic economic misfortune and increasing insecurity continues to increase on a daily basis; the youth constitute a significant percentage of that number. These young people are energetic, educated and capable of filling the labour gap in most European countries, created by demographic factors such as an ageing European population. Thus, revisiting restrictive policies against migrants in many European countries will benefit both receiving states and Africans.

The fact remains that human trafficking is closely linked with other organised crimes, such as drug smuggling, arms proliferation and terrorism. Greater multilateral diplomacy, including military action, has to be pursued by the international community against these crimes. However, these crimes are interlinked, and because of the continuous shrinking of national boundaries as a result of globalisation, there is every possibility of a spillover effect of what is happening in Libya to other parts of the region. If this is the case, we may very well end up returning to a dark time, similar to the 16th century trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Endnotes

- United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (n.d.) ‘Promoting Better Management of Migration in Nigeria (2011–2018)’, Available at: <https://www.unodc.org/nigeria/en/promoting-better-management-of-migration-in-nigeria-by-combating-and-reducing-irregular-migration.html>

- International Organisation for Migration (2017) ‘IOM Learns of ‘Slave Market’ Conditions Endangering Migrants in North Africa’, IOM press release, 4 November, Available at: <https://www.iom.int/news/iom-learns-slave-market-conditions-endangering-migrants-north-africa> [Accessed 29 November 2018].

- Ajodo-Adebanjoko, Angela (2017) Towards Ending Conflict and Insecurity in the Niger Delta Region: A Collective Non-violent Approach. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 17 (1), pp. 12–18.

- Alemika, Etannibi E.O. (2013) Organised Crime and Governance in West Africa: Overview. In Alemika, Etannibi E.O. (ed.) The Impact of Organised Crime on Governance in West Africa. Abuja: Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung, p. 24.

- Ibid.

- Egbuta, Ugwumba (2018) Africa’s Development Crisis and the Role of External Lending Institutions: Perspectives from Nigeria. Paper accepted for publication by the European Journal of Business and Management, paper: ISSN 2222-1905, online: ISSN 2222-2839.

- Afolayan, Adejumoke A. (1988) Immigration and Expulsion of ECOWAS Aliens in Nigeria. International Migration Review, 22 (1), pp. 4–27.

- National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) (2005) National HIV/Syphilis Sero-prevalence Sentinel Survey. Abuja: National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons and other Related Matters (NAPTIP).

- Obi, Paul (2017) ‘FG Lists Factors Fuelling Irregular Migration from Nigeria’, Thisday, 28 December, Available at:

<https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2017/12/28/fg-lists-factors-fuelling-irregular-migration-from-nigeria/> [Accessed 9 August 2018]. - Graham-Harrison, Emma (2017) ‘Migrants from West Africa Being “Sold in Libyan Slave Markets”’, The Guardian, 10 April, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/10/libya-public-slave-auctions-un-migration> [Accessed 7 December 2017].

- International Organisation for Migration (IOM) (2015) ‘Nigeria Adopts National Migration Policy’, 22 May, Available at: <https://www.iom.int/news/nigeria-adopts-national-migration-policy> [Accessed 28 November 2018].

- Ibid.

- BBC (2018) ‘Migrants Slavery in Libya: Nigerians Tell of Being Used as Slaves’, BBC Online, 2 January, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-42492687> [Accessed 18 December 2018].

- African Independent Television (AIT) (2018) Interview with Hon. Nnena Ukaeje, Chairperson, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Nigerian Parliament, on the Libyan Migrant Crisis, 18 October.

- Guggenheim, Scott and Cernea, Michael (1993) Anthropological Approaches to Involuntary Resettlement: Policy, Practice and Theory. In Cernea, Michael and Guggenheim, Scott (eds) Anthropological Approaches to Resettlement. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Ibid.

- United Nations (UN) (2017) ‘Security Council Presidential Statement Condemns Slave Trade of Migrants in Libya, Calls upon State Authorities to Comply with International Human Rights Law’, Presidential Statement S/PRST/2017/24, 7 December, SC/13105, Available at: <https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/sc13105.doc.htm> [Accessed 2 January 2019].

- CNN (2017) ‘People for Sale: Exposing Migrant Slave Auctions in Libya, Available at: <https://www.edition.cnn.com/special/africa/libya/libya-slave-auctions> [Accessed 2 January 2019].

- Peter, Fabricius (2017) ‘Libya Slave Trade Shocks AU-EU Leaders into Action’, Institute for Security Studies report, Available at: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/libyas-slave-trade-shocks-au-eu-leaders-into-action?utm_source=BenchmarkEmail&utm_campaign=ISS_Weekly&utm_medium=email> [Accessed 7 December 2017].

- Reuters (2017) ‘UN Evacuates First Group of Refugees from Libya to Niger’, 13 November, Available at: <http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=49851:un-evacuates-first-group-of-refugees-from-libya-to-niger&catid=52:Human%20Security> [Accessed 29 November 2018].

- Helfrich, Kim (2017) ‘Africa, EU Must Co-operate to End Migrant Abuse’, Defence News, 30 November, Available at: <http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50054:africa-eu-must-co-operate-to-end-migrant-abuse&catid=87:border-security> [Accessed 29 November 2018].

- Olowolagba, Fikayo (2017) ‘Libya Slave Trade: ECOWAS Reacts’, Daily Post, 30 November, Available at: <http://dailypost.ng/2017/11/30/libya-slave-trade-ecowas-reacts/>[Accessed 7 December 2017].

- Godwin, Ann, Ozioruva-Aliu, Alemma and Musa, Njadvara (2018) ‘FG Evacuates 1,490 Stranded Nigerians in Libya, Tasks States on Returnees’, Guardian News, 25 January, Available at: <https://guardian.ng/news/fg-evacuates-1490-stranded-nigerians-in-libya-tasks-states-on-returnees/> [Accessed 29 November 2018].