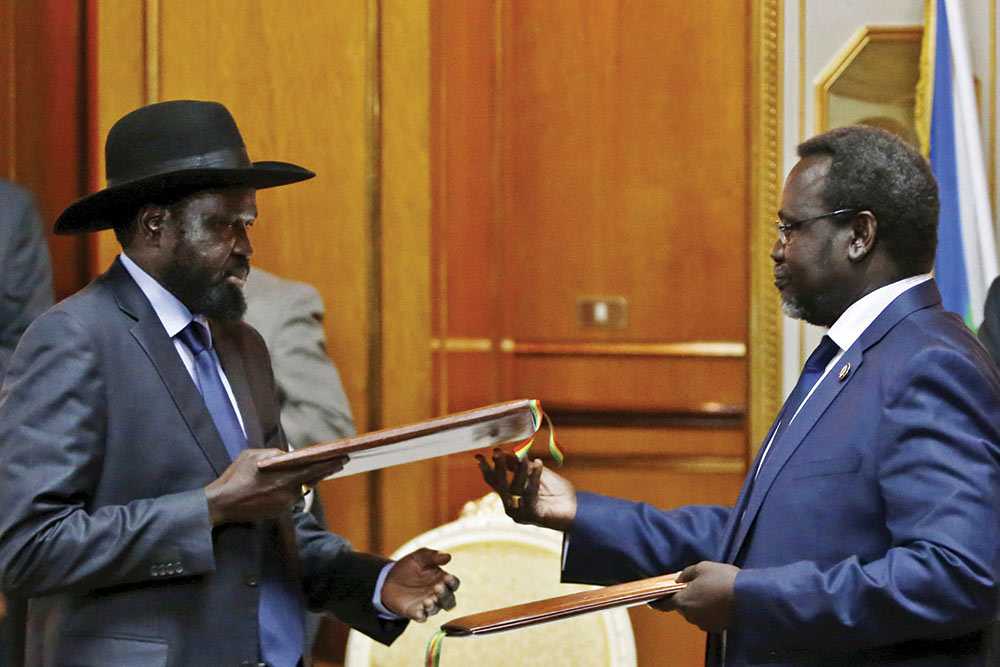

The date 12 January 2019 marked four months since the government of South Sudan, under the leadership of President Salva Kiir; the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition (SPLM-IO), under Riek Machar; and the South Sudan Opposition Alliance, among others, signed the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) in September 2018. The agreement stipulates that its implementation will be done in two stages. First, the Pre-Transitional Phase (PTP) has an eight-month time frame in which parties to the agreement, through the National Pre-Transitional Committee (NPTC), will prepare for the implementation of the R-ARCSS. Phase Two, effectively, is the implementation phase: a three-year period of a Revitalised Transnational Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) to begin at the end of the PTP. The three-year period of the RTGoNU is then to be followed by national elections.1

Although Kiir released some political prisoners and detainees in accordance with the R-ARCSS shortly after its signing, there was no shortage of concerns regarding whether the agreement would hold. The R-ARCSS – an endeavour to resuscitate its predecessor of 2015, the Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) – is the 12th such attempt at present to broker peace between the main opposition parties and end the conflict in the world’s newest state. If anything can be gleaned from the short South Sudanese past in relation to the conflict, it is that one has no reason to expect a significantly different outcome from the R-ARCSS. It could fall apart the way agreements that came before it did.

However, times have also changed, and there is a potentially different outcome that could be expected. At this juncture, Sudan to the north and Uganda to the south are much more “invested in peace” in South Sudan. For Sudan, not only does championing peace present President Omar Al-Bashir with the opportunity to rebrand himself regionally as a peacemaker, but it also diverts from the turmoil and uncertainty he faces at home because of the tanking Sudanese economy, which recently led to the declaration of a state of emergency.2 For Uganda, brokering peace not only allows it to counter recent credible reports of its role in arms supply to the South Sudanese warring parties, but it may provide the state with an opportunity to show a “positive” side of its interventionist politics in the region – if not quite a paradigm shift in its foreign policy.3 Uganda also faces an influx of thousands of South Sudanese refugees, displaced by the violence and insecurity in their home country. For both Sudan and Uganda, the war in South Sudan comes with significant costs, including economic challenges that only worsen with time.

This major departure in the R-ARCSS with regard to the role of Sudan and Uganda is perhaps best captured by Mahmood Mamdani. He states that the R-ARCSS is an agreement between Sudan and Uganda – “Mr Bashir and Mr Museveni are the guarantors of the agreement” – and by the R-ARCSS recognising them as such, it paves the way for South Sudan to become “an informal protectorate” of the two neighbours.4 Although it is an insight with potentially significant ramifications for the future of South Sudan, the recognition of the stakes that the two neighbours have in Juba and the power such recognition affords them points to the possibility of this peace agreement being “different” and perhaps “holding” differently. The extent to which one could call this potential different outcome “peace” is to be seen.

With South Sudan currently past the halfway point of the PTP, however, it is worth investigating the shape of the preparatory state for the implementation of the R-ARCSS and the level of progress made towards reaching Phase Two. After discussing the key features of the R-ARCSS for context, this article will trace the progress of the PTP in terms of key institutions and principles, and conclude with the implications of the state of the agreement on the creation of the RTGoNU.

Key features of the R-ARCSS

The agreement covers a wide range of issues that are critical to the achievement of peace in South Sudan. It unveils an elaborate power-sharing design, institutes support infrastructure for a permanent ceasefire and security within the country, outlines the process for facilitating access to humanitarian assistance, dictates ways for the management of economic and financial resources, stipulates the way forward with regard to transitional justice and accountability, articulates mechanisms for the creation of a permanent constitution, and outlines how the agreement is to be incorporated into the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan.

What stands out to most South Sudan observers is the structure of the executive as stipulated in the R-ARCSS. While Kiir and Machar maintain the presidency and the “first” vice presidency respectively (as has been the case in previous attempts at peace), the rest of the executive is to include four more vice presidents – one of whom “should be a woman”.5 On the one hand, this accommodationist approach ensures that various groups, often the loudest and usually the most aggressive, can have a piece of power and thereby introduce some stability in the system. On the other hand, this stability may be short-lived as the state embarks on calculating the degrees to which it is in what Philip Roessler calls the “coup-civil war trap” – wanting to keep opponents at bay and lowering the risk of a coup, yet increasing the chances of a civil war as these remote opponents build support outside the capital.6 This is particularly true in the context of South Sudan, where the level of trust between the president and his first vice president has been low, if at all existent. Certainly, the peculiarity of having five vice presidents has not escaped anyone, not in the least Kiir himself, who remarked, shortly after the signing of the agreement, that “South Sudan has become a field for experiments”.7

R-ARCSS Progress in the Pre-Transitional Phase

Examining evaluation reports from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and developments out of South Sudan in recent months, it is clear that the agreement is lagging behind due to bodies not constituted (or reconstituted) and the inability of those that are established to function. While some bodies – such as the NPTC, the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (RJMEC) and the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanism (CTSAMVM) – have been established in a timely manner, as stipulated by the R-ARCSS, many others were not until much later in the PTP. Key institutions with serious security implications – such as the Joint Defence Board (JDB), the Join Military Ceasefire Commission (JMCC) and the Joint Transitional Security Committee (JTSC) – were not established until late in November 2018, when they should have been established within two weeks of signing the agreement.8 As of the last IGAD RJMEC report from December 2018, two institutions were still outstanding: the Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration (DDR) Commission, and the Independent Boundaries Commission (IBC).

The bodies that have been formed, however, face the significant challenge of not having the funds necessary to carry out their responsibilities. In total, stakeholders say, US$280 million is required to implement the peace agreement. So far, less than US$3 million has been secured.9 In his opening remarks at the third CTSAMVM meeting on 22 January 2019, the chairman, Desta Abiche Ageno, voiced exactly this limitation: that budgetary constraints are hampering the body’s ability to deploy monitors and to carry out the work of keeping parties accountable.10 Similarly, the RJMEC emphasised the toll the lack of funds has on the agreement at its third plenary session, noting that the restriction is “impacting on the smooth implementation of the tasks and activities” that are necessary for a successful pre-transitional period.11 Funding the peace is such an obstacle that in February 2019, Kiir decided to cut the pay-checks of public servants from March until June 2019, to fund the peace process.12 This decision is rather paradoxical, given multiple reports showing that South Sudanese workers are not paid appropriate salaries and are rarely paid on time. For all intents and purposes, the government has already deducted the public’s financial contribution to the peace implementation.

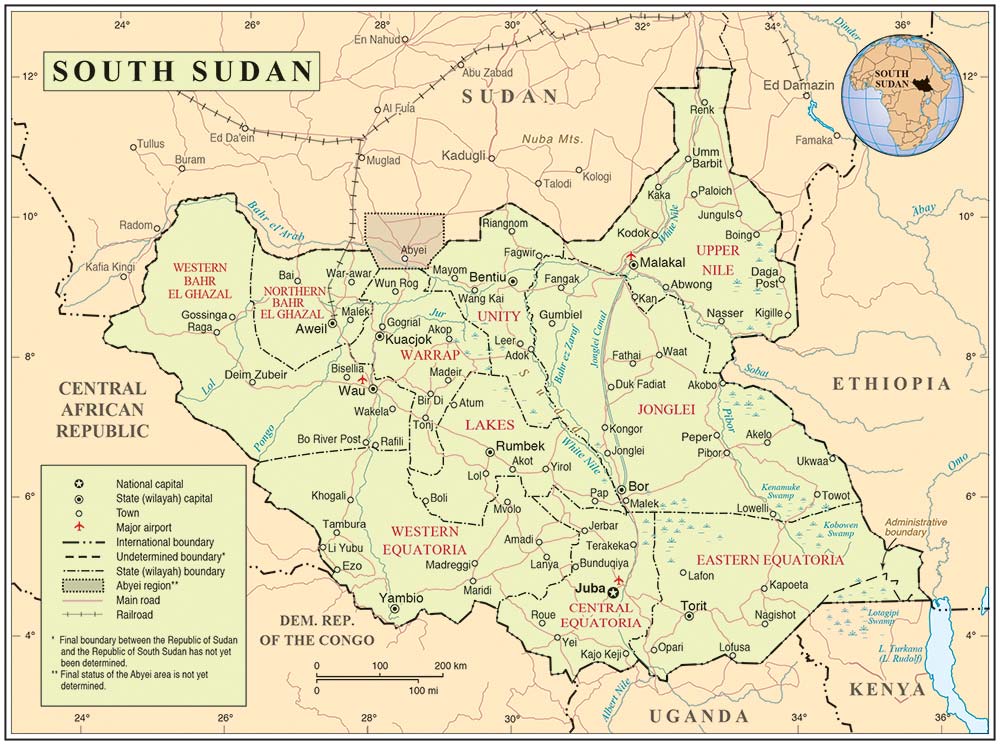

One of the central institutions that is yet to be created, the IBC, is of particular interest at this juncture. This committee has an important role to play with regard to the issue of states, which has been a point of contention since it rose to national and international attention in 2015 through a presidential decree that created 28 states just months after the ARCSS was signed. Despite the backlash from Kiir’s political opponents, the issue was “handled” unilaterally once again by the president in 2017, further increasing the number of states to 32. The R-ARCSS specifies the timeline and mechanism through which the internal boundaries of states within South Sudan should be resolved. Within two weeks of the signing of the R-ARCSS, the IBC – chaired by non-South Sudanese and composed of members to be nominated by the various South Sudanese stakeholders, as well as members of the African Union (AU) ad hoc committee on South Sudan – was supposed to have been formed.

According to the R-ARCSS, the purpose of the IBC is to “consider the number of States” and their boundaries along with the “composition and the restructuring” of the Council of States, the upper house of the South Sudanese Legislative Assembly.13 The National Democratic Movement’s (NDM) mid-term evaluation report from January 2019 indicates that the necessary membership recommendations for the establishment of the IBC have already been made by the South Sudanese parties to the agreement.14 At this moment, notwithstanding the financial restrictions, it is unclear what the obstacles blocking the formation of the IBC are.

However, there has been some positive movement recently – albeit close to five months behind schedule – with the establishment of the Technical Boundary Committee (TBC) on 7 January 2019. Made up of experts from IGAD and Troika countries.15 the TBC is tasked with defining and demarcating “tribal areas of South Sudan as they stood on 1 January 1956”, as well as all disputed tribal areas.16 The TBC is mandated by the R-ARCSS to complete its work within 60 days – it aims to carry out public consultations, study archival and historical records, and run cartographic analyses to delineate tribal boundaries.17 In line with its mandate to involve the public, the TBC made a “call for submissions” on 22 January 2019, asking individuals and entities to provide “the list and description of tribal boundaries… in disputes as a result of the creation of 32 States in the Republic of South Sudan…”18 It must be noted, however, that although both the TBC and the IBC are linked in subsections of Chapter 1.15 of the R-ARCSS, the agreement is not clear as to what links – if any – there are between the two.

One can assume some educated guesses on the potential connection between the two bodies. Many students and observers of South Sudan – along with Kiir’s political opponents –have highlighted the tribalist pattern in which the new states were established in 2015 and 2017. In their wake, the states created new tensions and opportunities for violence in some areas, while escalating existing conflicts in others. Speaking at a TBC preliminary meeting in December 2018, the JMEC’s interim chair, Augostino Njoroge, further cemented the links between the tribal borders and the eventual recommendations the IBC may someday make. He remarked that the “findings of [the TBC] over the next two months will provide the basis, which can help the [IBC] to make a determination, on the number and boundaries of States in South Sudan”.19

The most immediate and practical challenge to the TBC is the feasibility of conducting all of its aforementioned tasks within 60 days, as stipulated in the R-ARCSS – noting, once again, the financial burden with which it has to contend. The bigger challenge – not just for the TBC, but for South Sudan as it wrestles to build a functioning nation-state – is seriously investigating what it means to define tribal territories, and what implications such definitions have on those boundaries to be divided or consolidated into states and on the people who will live in and between them. As Matthew Pritchard observes, “Rather than being ahistorical or apolitical givens, boundaries and the territories they define, create and are created by historically-rooted debates over power, identity, and political authority.”20 The work of the TBC is certainly valuable, but the extent to which its findings should and can bear on the number of states requires further consideration.

Beyond institutions and bodies formed, delayed and underfunded, the first half of the PTP shows that key principles to which parties have agreed are proving to be difficult to uphold. One major area of concern has been the cessation of hostilities among warring parties and the absence of demonstrable goodwill. The various parties’ commitment to the Permanent Ceasefire of the 2018 Khartoum Declaration and the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement of 2017 has proven to be lacking. As late as December 2018, for example, the CTSAMVM reported instances of recruitment and training of fighters in Unity State, clashes between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) and the South Sudan National Movement for Change, incendiary military actions by the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces in Wau, clashes between signatories and non-signatories to the R-ARCSS, and the denial of access by government and SPLM-IO forces to CTSAMVM peace verification monitors.21

Three particular events seem to epitomise the absence of goodwill. The first is the infamous “Luri incident” on 18 December 2018, where grave abuses towards the CTSAMVM’s monitoring team members were committed as they attempted to access a government-controlled site. Members of the team were assaulted, “subjected to physical and emotional violence (stripped of their clothing, blindfolded, handcuffed, made to kneel for a considerable time and verbally threatened) while in detention for at least five hours.”22 For those jaded by the mistreatment of South Sudanese by their own government, what was of note in the Luri incident is that even the international make-up of this monitoring team did not provide some safety of shield to its foreign members.

The second event indicating the absence of goodwill is the obstruction of humanitarian aid delivery. The RJMEC’s quarterly report, released in January 2019, noted that humanitarian aid organisations and their workers were denied access to sites by various political actors. Furthermore, these organisations and their aid workers have also experienced direct violence – primarily from state forces, but also from non-state actors and other civilians – leading to a total of 14 aid workers killed in 2018.23 Needless to say, these attacks affect the security of these organisations, their staff and their overall ability to deliver needed goods and services to vulnerable populations.

The third point is the continued detention of prisoners of war. The R-ARCSS stipulates that all prisoners are to be released at the signing of the agreement. Although Kiir gestured his reception of this stipulation early in October 2018 by releasing some prisoners, the NDM argues in its evaluation of the agreement that many more prisoners remain behind bars.

Counting as violations of the R-ARCSS on multiple levels, these three actions serve to further undermine any trust between the parties to the agreement. They similarly erode public trust – if it exists at all – in the commitment of political actors to change the trajectory of South Sudan towards peace.

Implications

The PTP presents South Sudan with some significant challenges in the second half of this phase, as well as into Phase Two. The first among these challenges hinges on the ability to draw a distinction between timeously creating institutions, as stipulated in the R-ARCSS and then being able to financially operationalise those institutions. Although the delay is noteworthy, as it is indicative of a lack of will or planning on the part of key players, the inability of a body to carry out expected tasks once it is formed is perhaps more debilitating and discouraging in this attempt at peace. IGAD and the JMEC call on friends of South Sudan to help with funding, but “funding the peace” should ultimately be a burden that the South Sudanese government and its opponents carry – not the already-burdened public servant. The corollary of this challenge is that the financial constraints which stagnate the PTP will likely result in a slow and less transformative transitional period. What this may mean for Phase Two is that South Sudan ventures into it unprepared, or that this phase will take place much later than currently anticipated.

In this regard, one particular delay that is worth further examination pertains to the TBC and the IBC. Doubts are already cast on the TBC’s ability to realistically carry out its work (well) within 60 days. This time frame is likely to be extended if financial limitations are factored in. On the one hand, if the currently non-existent IBC is supposed to make recommendations based on the TBC, the IBC will likely take longer than originally anticipated to come into being. If the IBC never comes to fruition by the end of the PTP, the issue of states and boundaries becomes very complex. The R-ARCSS states that, in the “unlikely event the IBC [fails] to make its final report” by the end of the PTP, the IBC will transform into the Referendum Commission on the Number and Boundaries of States (RCNBS).24 The RCNBS is tasked with carrying out a referendum to decide the number of states within South Sudan, prior to the beginning of Phase Two.

Given that the IBC has about three months to come to fruition before the end of the PTP, what does it mean to become a RCNBS without having gone through the process of being an IBC? What does it mean to have a referendum on the number of states without the work the IBC is supposed to carry out? On the one hand, turning the decision on the number of states to the people may be a fair approach; they get to make a choice. On the other hand, without the consultative work of the IBC, two potential challenges may present themselves. First, negotiating what number of states to propose on the ballot may prove controversial. Although the 10 post-independence states and the 21 colonial districts have some resonance in South Sudanese debates, the logic behind 28 and 32 states does not preclude increasing these numbers. Regarding the idea of a referendum on a contentious subject prior to the beginning of Phase Two, its timing may introduce or reinforce some uncertainty and instability, depending on the proposed number of states – which would have serious implications for the make-up of the Council of States. These are questions that are particularly relevant as the point of shifting to the RTGoNU quickly approaches.

Conclusion

The PTP seems to be successful, if success is defined very narrowly. Most of the institutions the R-ARCSS calls for have now been created. Funding constraints, however, take away from any claims of success, as these institutions are debilitated and do not have the necessary funding to execute their tasks. One of the institutions that is yet to be established – the IBC – has some significant implications for the make-up of the National Assembly. It may have even more negative implications for overall stability if it is never created and is made to transition into the RCNBS instead. The signatories to the agreement, in continuing to behave as warring parties by hindering humanitarian aid, not releasing prisoners and not allowing PTP bodies to carry out their work, undermine their trust in one another and the trust of the public in this peace actually holding. The implications of the agreement in its current phase on its future will only be further illuminated over the next few months, as involved parties consider what can be done with what is financially and structurally available and, collectively, how well these two dimensions prepare South Sudan for a revitalised government of national unity.

Endnotes

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) (2018) ‘Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS)’, Available at: <https://www.dropbox.com/s/6dn3477q3f5472d/R-ARCSS.2018-i.pdf?dl=0> [Accessed 18 September 2018].

- The Washington Post (2019) ‘Sudan Declares State of Emergency-Disbands Cabinet’, 22 February, Available at: <https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/sudan-declares-state-of-emergency-disbands-cabinet/2019/02/22/b21097ca-36e6-11e9-8375-e3dcf6b68558_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.c2aa38b24428>

[Accessed 26 February 2019]. - Conflict Armament Research (2018) ‘Weapons Supply into South Sudan’s Civil War’, Available at: <http://www.conflictarm.com/reports/weapon-supplies-into-south-sudans-civil-war/>

[Accessed 26 February 2019]. - Mamdani, Mahmood (2018) ‘The Trouble with South Sudan’s New Peace Deal’, The New York Times, 24 September,

Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/24/opinion/south-sudan-peace-agreement.html>

[Accessed 25 September 2018]. - IGAD (2018) op. cit.

- Rosseler, Phillip (2016) Ethnic Politics and State Power in Africa: The Logic of the Coup-Civil War Trap. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oduha, Joseph (2018) ‘Kiir Criticizes the Five Vice-Presidents Formula’ (2018), Gurtong, 19 July, Available at: <http://www.gurtong.net/ECM/Editorial/tabid/124/ctl/ArticleView/mid/519/articleId/21536/Kiir-Criticises-The-Five-Vice-Presidents-Formula.aspx> [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC) (2019a) ‘On the Status of the Implementation of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan’, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/reports/jmec-quarterly-reports/126-rjmec-quarterly-report-to-igad-on-the-status-of-implementation-of-the-r-arcss-from-1st-october-to-31st-december-2018/file> [Accessed 25 February 2019].

- Sudan Tribune (2019) ‘South Sudan to Cut One Day’s Pay for Peace Implementation’, Reliefweb, 13 February, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-cut-one-day-s-pay-peace-implementation> [Accessed 26 February 2019].

- Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM) (2019) ‘Opening Remarks from the CTSAMVM Chairman at the 3rd CTSAMVM Board Meeting’, Available at: <http://ctsamm.org/opening-remarks-from-the-ctsamvm-chairman-at-the-3rd-ctsamvm-board-meeting/> [Accessed 22 January 2019].

- JMEC (2019b) ‘Resolutions of the RJMEC: 3rd RJMEC Plenary’, Available at: <https://www.jmecsouthsudan.com/index.php/plenary/plenary-resolutions/124-resolutions-of-the-3rd-rjmec-plenary-palm-africa-hotel-23rd-january-2019-juba-south-sudan-1/file> [Accessed 24 January 2019].

- Cirino, Winnie and Tanza, John (2019) ‘South Sudan to Deduct from Civil Servants Salaries – But Salaries are Not being Paid’, VOA, 18 February, Available at: <https://www.voanews.com/a/south-sudan-to-deduct-from-civil-servants-salaries—-but-salaries-aren-t-being-paid/4792212.html> [Accessed 27 February 2019].

- IGAD (2018) op. cit.

- National Democratic Movement (2019) ‘Mid-term Evaluation of the Implementation of the Pre-Transition Activities of the R-ARCSS’, Personal correspondence/communication, 20 January.

- Norway, United States, United Kingdom.

- IGAD (2019) ‘Technical Boundary Committee: Call for Submission’, Personal correspondence/communication, 20 January.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- JMEC (2018a) ‘TBC Holds its Inaugural Meeting in Juba’, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/media-center/news/item/397-tbc-hold-its-inaugural-meeting-in-juba> [Accessed 10 December 2018].

- Johnson, Douglas, Verjee, Aly and Pritchard, Matthew (2018) After the Khartoum Agreement: Boundary Making and the 32 States in South Sudan. Rift Valley Institute Briefing Paper, pp. 1–4.

- JMEC (2018b) ‘On the Status of Implementation of the R-ARCSS 2018’, Available at: <https://jmecsouthsudan.org/index.php/reports/r-arcss-evaluation-reports/117-progress-report-no-4-on-the-status-of-implementation-of-the-r-arcss-2018-december-10-2018/file> [Accessed 12 December 2018].

- JMEC (2019a) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- IGAD (2018) op. cit.