Introduction

Like other articles in this special issue of Conflict Trends taking stock of what has been achieved in the wake of the uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East in 2011, this contribution examines what has transpired in Libya over the last four years. The United Nations (UN) Resolution 1973 that authorised a no-fly zone over Libya was widely criticised for its implementation by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Given its substantial role in the downfall of Muammar Gaddafi’s government, the international community – including multilateral and regional organisations – bear some responsibility for what has transpired since. As predicted by a key international observer in 2011, during the throes of the early part of the civil war, “Libyans’ hopes for freedom and legitimate government… depend on how and when Qaddafi goes.”1

In February 2011, spontaneous street protests commenced in a few Libyan cities, sparked by the arrest of a human rights campaigner in the eastern city of Benghazi. These occurred in the aftermath of similar popular protests – which occurred for different reasons – in Tunisia and Egypt. This initial spurt of popular unrest and instability in Libya quickly morphed into a fully-fledged armed conflict. Resisted by Gaddafi and his forces, the protests and resulting conflict rapidly descended into a months-long civil war, and culminated in the capture and killing of Gaddafi on 20 October 2011. This period saw intense deliberation and action by global actors in attempts to curtail the violence that was raging through Libya. The African Union (AU) became immediately concerned with the situation rapidly unfolding in Libya, and its first discussion on the crisis occurred at the Peace and Security Council (PSC) meeting on 23 February 2011. Its 10 March 2011 meeting, also at the level of heads of state, saw the crafting of a definitive response to the crisis. This involved a ‘roadmap’, encapsulated by the following: “The current situation in Libya calls for an urgent African action for: (i) the immediate cessation of all hostilities, (ii) the cooperation of the competent Libyan authorities to facilitate the timely delivery of humanitarian assistance to the needy populations, (iii) the protection of foreign nationals, including the African migrants living in Libya, and (iv) the adoption and implementation of the political reforms necessary for the elimination of the causes of the current crisis.”2 At the time, this approach was deemed indecisive, and a key weakness was its failure to spell out an exit strategy for Gaddafi.3 The roadmap was, unfortunately, immediately sidelined. In the UN, United Kingdom (UK) and France, and to a lesser extent, the United States (US), sought to act decisively to assist the rebel forces. The UK, as chair of the UN Security Council at the time, drafted Resolution 1973.

A full week after the release of the AU Communiqué on 10 March 2011, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973 that authorised a no-fly zone over Libya. This measure, implemented by NATO, aided the cause of the National Transitional Council (NTC) that ultimately overran Tripoli in August 2011, storming Gaddafi’s compound and sending him into hiding. Not long after this, the AU joined 60 countries in recognising the NTC as the rightful occupant of the Libyan seat in the organisation.4 In fact, the NTC had already been recognised by the International Contact Group (ICG) on Libya as the legitimate authority in the country as early as July 2011. The ICG is a gathering of 21 countries and representatives of various states, regional bodies and global multilateral organisations. After its inaugural meeting on 13 April 2011, it declared that “Qadhafi and his regime had lost all legitimacy and he must leave power allowing the Libyan people to determine their own future”.5 It should be noted that not one member of this group is an African state, with Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan and Tunisia, along with the AU, accorded observer status.

Power struggles within the NTC, competition for oil riches and a lack of agreement on the way forward on national reconciliation have all hampered Libya’s transition from post-Gaddafi rule. This article provides an overview of events in Libya since the NATO intervention, and examines the varied responses to the conflict from the international community.

Libya in Transition

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in 2010 Libya ranked 53rd out of 163 countries in the UN’s Human Development Index. Classified a high human development country among the countries of the Middle East and North African region, Libya’s population of 5.6 million boasted an adult literacy rate of 88.4%. The gross national income (GNI) per capita was US$12 637.6 It was thought that structural features of the country such as “ethno-religious homogeneity, ample oil revenues and robust infrastructure suggested a less contentious transition than elsewhere”.7 According to the UNDP, with demographic changes over the last three decades in Libya, a current feature of the country’s population pyramid is that it is characterised by a ‘youth bulge’ or a large proportion of 25- to 29-year-olds, which includes a substantial number of young men who are unemployed. The crisis was fed by this demographic feature, as “(y)outh were the main building block of the revolution and women played a key supporting role in food and healthcare supply to the fighters, information and transport/ smuggling of arms”.8 This and other challenges, including the ready availability of weapons and a lack of agreement among key actors, have rendered Libya’s transition slow and, at times, violent.

The Security Transition

Among the key grievances against the Gaddafi regime were the inequitable distribution of oil revenues and violations of human rights. While the NATO operation aided the NTC in defeating Gaddafi’s regime, the Western coalition chose a side with such speed that the requirement of building a united and comprehensive front to oppose Gaddafi and constructing a new Libya after the uprising was not met. This was in spite of a call by the ICG on Libya for “an inclusive political process so that the Libyan people can determine their own future”.9 The anti-regime militias that opposed Gaddafi had organised themselves into three confederations, determined by their geographical origins: Eastern Libya, Misrata and the Nafousa Mountains. By the time of Gaddafi’s demise, these militia groups numbered some 1 700 – a total of 231 000 registered fighters.10

The NTC and Libya’s first elected government in 2012 struggled to attain a monopoly of force, one of the key characteristics of state authority. The vast numbers of fighters who were engaged in the battle against Gaddafi had to be disarmed and reintegrated into Libyan society. The interim NTC and the first democratically elected government sought to manage this challenge in three main ways: co-opting militias to bolster security in key areas; attempting to transfer fighters into the state’s official, rebuilt armed forces; and demobilising and reintegrating militia forces. All these measures required significant resources and time to implement. Unfortunately, the continuing inability of Libya’s post-Gaddafi governments to realise a monopoly of force represented an opportunity for ‘entrepreneurs of violence’ to enter the scene and utilise the security vacuum to their own ends.11

Military challenges to the state’s authority emerged first in June 2012, when jihadists organised a military rally in Benghazi. This was followed a year later by a federalist challenge, in July 2013. Recognising the glaring weaknesses in the state’s ability to impose military control over the country, veteran jihadists (those who had previously fought in Afghanistan against Russia in the 1980s, among others)12 who had played a role in the 2011 revolution began to flex their muscles in the eastern town in which the anti-Gaddafi uprisings commenced. Capitalising upon the state’s inability to manage this challenge, federalists, also in the east, sought a decentralisation of political power to address decades of meagre benefit from Libya’s oil wealth, in spite of two-thirds of Libya’s oil reserves being situated in the east.13 Although it enlisted the assistance of militias to quell these threats, the government could not depend on their loyalty, and it made some critical errors, costing it victory over the new armed threats, and legitimacy among the Libyan population. The government’s resistance to the twin challenges reached a stalemate by the end of 2013, but still, Libya’s further descent into conflict and lawlessness was not inevitable.14 This was precipitated by an equally complex series of political crises.

The Political Transition and the 2014 Crisis

Gaddafi’s demise left Libya in political limbo. After decades of divide-and-rule, simmering tensions boiled over and communities took up arms against each other. Yet local authorities, through their appeals to keep the country whole and to uphold Libyan identity and Islamic values, retained a valuable role in seeking to end fighting quickly and initiating negotiations that could lead to lasting ceasefires. At times, Libya seemed to be one of the success stories of the ‘Arab Spring’, holding elections in June 2012 in which voter turnout was recorded at 62%.15 This election, while widely heralded as a great triumph for the Libyan people, took place under tense circumstances. Extreme federalists in the east refused to participate, leaving them marginalised from the eventual elected national assembly and unable to voice their interests in the legislature. Simmering tensions within the NTC boiled over into clashes in Benghazi in January 2012. NTC officials in the eastern town launched a campaign for greater autonomy two months later in March. Meanwhile, the government also struggled to maintain control over local militias in Zintan, in the west of the country. Nonetheless, elections were held, ushering in a moderate coalition, as the largest party of the newly formed General National Congress (GNC). Unlike the outcomes in Egypt and Tunisia, the Muslim Brotherhood secured only 17 seats in the Libyan election. Mohammed Magarief was elected the interim head of state by parliament, later to be replaced by Libya’s first elected prime minister, Ali Zeidan, a liberal and opposition envoy during the 2011 conflict. A new constitution remained to be drafted and approved. It would serve as the basis for new elections by February 2014.

Due to a number of challenges, including inefficient state bodies and the security situation, these events did not materialise and the mandate of the interim Constituent Assembly was reluctantly extended by a year. During this time, Zeidan faced a number of challenges, ultimately leading to his dismissal. Businessman Ahmed Maiteg was elected his successor in March 2014. This transition in leadership presented a chance for the self-styled Libyan National Army renegade, General Khalifa Haftar, to rally elements in the armed forces to oppose what he argued was an Islamist-controlled legislature under Maiteg. Haftar’s forces launched attacks on Tripoli and Benghazi in May 2014. Meanwhile, the GNC speaker, Nouri Abusahmain, called upon the Libyan Shield Forces (LSF) to defend the legislature. A Shura Council16 was formed in Benghazi to unite formerly disparate Islamist militias, in response to Haftar’s attacks. These battles caused untold infrastructural and institutional damage.17

In a bid to repair the latter, the GNC finally held elections in late June 2014, with a promise to convene in Benghazi to appease the east. Election turnout was low, compromising the legitimacy of the results. To add to matters, Islamists suffered heavy defeats, resulting in an outbreak of hostilities between those loyal to the old parliament and forces defending the new parliament. Given the protracted violence in Benghazi, the GNC was forced to meet in Tobruk. This did not sit well with those parliamentarians, including from Misrata and Islamist parties, who saw Tobruk as a Haftar stronghold. They refused to participate in parliament in Tobruk and joined forces in Tripoli with those members of parliament who had not been re-elected, to form a ‘rump parliament’, which voted against the newly elected parliament.18 The parliament elected in June 2014 was subsequently ruled unlawful by the Libya Supreme Court, whose impartiality was questioned by some due to its location in Tripoli, which is currently, at the time of writing, under the control of Islamist forces.

The situation descended to new depths in mid-2014, with the withdrawal of foreign diplomats, UN staff and other foreign workers, as well as the takeover of Tripoli airport by Libya Dawn, a group based in the city of Misrata, in September 2014. Another group, Ansar al-Sharia, which had previously enjoyed little popular support in the aftermath of its attack on the US embassy in September 2012 that claimed the life of the US ambassador, seized control of most of Benghazi by the end of July 2014.

A new development is the arrival of the Islamic State (IS) in Libya. According to news reports, the extremists seized control of the port of Derna in eastern Libya in October 2014. The Libyan army has regained some initiative in Benghazi and has sought to roll back the victories of IS in Derna and Libya Dawn in western Libya. Meetings in Geneva at the start of 2015 saw UN efforts to hold talks between the belligerents rewarded, with the declaration of a ceasefire in January.

The Conflict and the International Community’s Response

UN Resolution 1973 authorising a no-fly zone over Libya on 17 March 2011, while it acknowledged the AU’s efforts to develop a roadmap to peace through political reform among other things, sought mainly to end the Gaddafi regime. The subsequent efforts of members of the international community, such as the ICG for Libya, also predicated all of its discussions upon the conviction that no progress could be made while Gaddafi remained in power, regardless of how cornered he was. The implementation of the armed measures against Gaddafi’s regime, while they assisted greatly in bringing the initial conflict to a speedy conclusion, had the unintended effect of handing victory to a loose coalition of militia groups with no unified political vision for the country, and with far less in common.

The AU, for its part, sustained a beating to its reputation for decisive responses to crises, because of the manner in which its well-intentioned roadmap was perceived and reported upon in the Western media. This prompted former AU Commission chairman, Jean Ping, to release a terse defence of AU policy on Libya later in the year, which clarified many misconceptions.19 Many questions were also asked of Africa’s three non-permanent Security Council members – South Africa, Nigeria and Gabon – which, if they had only abstained, as Germany, Brazil and India did, would have forestalled the resort to force by external actors in Libya – a course of action ostensibly in line with the stated position of the continental body.

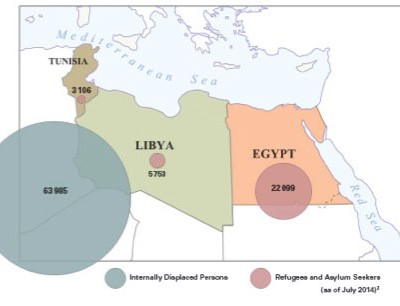

The conflict has potentially wide-ranging impacts on a variety of actors. The proliferation of arms and militias in Libya as a result of the 2011 conflict, and their easy transport through the Saharan region of southern Libya, has already been cited as a contributing factor to the uprising in the north of Mali in January 2012.20 Weapons looted from Gaddafi’s stockpiles have also reportedly surfaced in Egypt, Gaza, Chad, Lebanon and Syria.21 The easy availability of arms has also been linked to the failure to consolidate the rebel fronts, as splintering was facilitated by access to arms.22

While discussions between the main protagonists in the conflict have been convened in Geneva, starting in early 2015, major international players appear slow to learn from past mistakes in picking favourites on the Libyan political scene. There has been muted response to the Supreme Court’s decision to declare the 2014 parliament unlawful. This may be interpreted as tacit support for the anti-Islamist parliament that sits in Tobruk. While this may be in accord with certain Western interests, it may not be the best way to keep the key actors at the negotiating table in a bid to initiate a long-overdue national dialogue.

The Geneva talks have been convened by the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), in the context of a rapidly worsening security situation. Libya Dawn has thus far refused to participate in the peace talks, while the presence of IS in Libya is growing – appearing to be capitalising on the lack of authority and order in the governing of Libya. January 2015 saw a bold attack on a Tripoli hotel, followed in February by the reported beheadings of some 21 Coptic Christians on a remote Libyan beach, purportedly by IS. The growing presence of militants in Libya is drawing the country’s neighbours, especially Egypt, into the complex security dilemmas Libya faces.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of Gaddafi’s capture and murder in October 2011, some critics asked whether it would not have been better for him to be captured, rather than killed. There is now the realisation that the manner of Gaddafi’s departure does have far-reaching implications for long-term peace and stability in Libya. Soon after Gaddafi’s death, the law hastily proclaimed that no person linked to the Gaddafi regime may hold office in the new administration, and revealed how shallow the roots of reconciliation were upon which the new dispensation would be based. This law was repealed in February 2015.

The spontaneous and sporadic nature of the initial protests and armed uprisings has given the conflict a remarkably local and splintered nature, necessitating the rebuilding of the country from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, hence the involvement of municipal and council leaders in the Geneva talks. This should be seen as a constructive measure that, if implemented four years ago, may have initiated Libya’s road to recovery far sooner.

Much now hinges upon the extent to which the international community places Libya’s reconstruction at the top of the agenda. With the historic plunge in the oil price since the end of 2014, Libya’s reconstruction and efforts at post-conflict peacebuilding hang in the balance. Payments to co-opted security forces and to both parliaments, along with the replacement of infrastructure destroyed during the conflict, may be threatened by diminished oil revenues. This will further harm the prospects for peace and potentially create new humanitarian crises. However, new security developments in Libya, including the arrival of IS forces, may finally focus minds on initiating significant efforts at building lasting peace in the country.

Endnotes

- International Crisis Group (ICG) (2011) ‘Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (V): Making Sense of Libya’, Middle East/North Africa Report No. 107, 6 June 2011, Available at: <http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya/107-popular-protest-in-north-africa-and-the-middle-east-v-making-sense-of-libya.aspx> [Accessed 8 February 2015].

- African Union Peace and Security Council (2011) ‘Communique of the 265th meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, PSC/PR/COMM.2 (CCLXV), 10 March, Available at: <http://www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/COMMUNIQUE_EN_10_MARCH_2011_PSD_THE_265TH_MEETING_OF_THE_PEACE_AND_SECURITY_COUNCIL_ADOPTED_FOLLOWING_DECISION_SITUATION_LIBYA.pdf> [Accessed 16 February 2015].

- De Waal, Alex (2012) ‘The African Union and the Libya Conflict, World Peace Foundation, Available at: <http://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2012/12/19/the-african-union-and-the-libya-conflict-of-2011/> [Accessed 8 February 2015].

- BBC (2015) ‘Libya Profile’, Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13755445> [Accessed 7 February 2015].

- Libya Contact Group (2011) ‘Statement by Foreign Secretary William Hague Following the Libya Contact Group Meeting in Doha (Chair’s Statement)’, 13 April, Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/libya-contact-group-chairs-statement> [Accessed 8 February 2015].

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (n.d.) ‘About Libya’, Available at: <http://www.ly.undp.org/content/libya/en/home/countryinfo.html> [Accessed 16 February 2015].

- Devore, Marc C. (2014) Profile: Exploiting Anarchy: Violent Entrepreneurs and the Collapse of Libya’s Post- Qadhafi Settlement. Mediterranean Politics, 19 (3), pp. 463–470.

- UNDP (n.d.) op. cit. [Accessed 7 February 2015].

- Libya Contact Group (2011) op. cit.

- Devore, Marc C. (2014) op. cit., p. 464.

- Ibid., p. 465.

- Ibid., p. 466.

- Ibid., p. 467.

- Ibid.

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) (2011) ‘Voter Turnout Data for Libya’, Available at: <http://www.idea.int/vt/countryview.cfm?CountryCode=LY> [Accessed 16 February 2015].

- This term refers to a body with a consultative or advisory role.

- Devore, Marc C. (2014) op. cit., p. 469.

- Ibid. and BBC (2015) op. cit.

- Ping, Jean (2011) ‘African Union Role in the Libyan Crisis’, Pambazuka News, 563, Available at: <http://www.pambazuka.net/en/category/aumonitor/78691> [Accessed 8 February 2015].

- Chivers, C.J. (2013) ‘Looted Libyan Arms in Mali May have Shifted Conflict’s Path’, New York Times, 7 February. Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/08/world/africa/looted-libyan-arms-in-mali-may-have-shifted-conflicts-path.html> [Accessed 8 February 2015].

- Ibid.

- Strazzari, Francesco and Tholens, Simone (2014) ‘Tesco for Terrorists’ Reconsidered: Arms and Conflict Dynamics in Libya and in the Sahara-Sahel Region. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 20 (3), pp. 343–360.