Over the past 15 years, the AU–UN partnership in peace and security has evolved significantly, both in breadth and depth.1 Member states on the AUPSC and the UN Security Council (UNSC) convene annually, with the three rotating African members of the UNSC (the A3) playing an informal bridging role throughout the year. The AU Commission and UN Secretariat are spearheading the partnership’s shift away from a collection of ad hoc engagements towards a more strategic and predictable relationship, increasingly based on mutual respect and the recognition of comparative advantages.2 Beyond the AU and UN’s frequent interactions on country-specific issues, cooperation has flourished across a diverse set of thematic priorities – from mediation support and the women, peace and security agenda to disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) processes.

Nonetheless, the partnership faces obstacles to the full realisation of its shared goal of a conflict-free African continent. Debates over political primacy and institutional leadership narrow cooperation on the most sensitive files such as Libya or Cameroon. Unresolved questions concerning financial resources and burden-sharing in peacekeeping and counter-extremism efforts continue to linger. But despite these roadblocks, the prevailing international climate underscores the political, financial and operational reality that neither the AU nor the UN can prevent conflicts and manage crises on their own. In this light, the silencing the guns (STG) agenda can be a catalyst for strengthening the partnership’s long-term foundation, with positive consequences for both the AU’s Agenda 2063 long-term development vision as well as the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

This article discusses AU–UN cooperation to date on the STG agenda and identifies priorities for the partnership to sustain this initiative beyond 2020. It argues that a strong AU–UN partnership is critical to consolidating political buy-in and overcoming policy gaps on the STG agenda, especially as they relate to collective conflict prevention and crisis management efforts. It also discusses how AU–UN efforts on these issues will need to evolve to effectively achieve the initiative’s ambitious commitments and the overarching goals expressed within the 2030 Agenda and Agenda 2063.3

Why the STG agenda matters for the AU–UN partnership

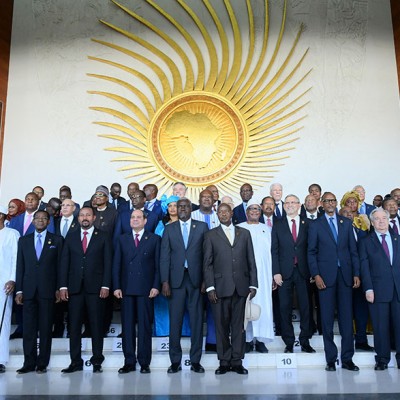

The STG agenda encapsulates many of the strategic priorities underpinning the AU–UN partnership in peace and security. It emerged from the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government with a commitment to “end all wars in Africa by 2020” in its 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration.4 This commitment has since been elaborated by the Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by Year 2020 (the AUMR), endorsed by the AUPSC in late 2016.5 Through a holistic and integrated approach to peace, security and development, the STG agenda aims to, inter alia, address the root causes of conflict in Africa, strengthen the continent’s capacities for peace, and support the African Peace and Security Architecture’s (APSA) mechanisms for conflict prevention, peacemaking, peace support, and post-conflict reconstruction and development (PCRD).

The AUMR, developed nearly three-and-a-half years after the 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration, serves as the STG agenda’s policy foundation. It articulates a comprehensive approach for pursuing peace, security and socio-economic development simultaneously as necessary steps to end all wars on the continent. The AUMR’s detailed “implementable steps” in the political, governance, socio-economic, social, environmental and legal dimensions therefore ask AU member states to approach structural conflict prevention from a much broader perspective than approaches confined narrowly to the peace and security space.6 This multifaceted approach to conflict prevention also aligns strongly with the UN’s peacebuilding and sustaining peace agendas.7 Specific to the AU–UN partnership, the AUMR’s recommendations include more frequent dialogue between the AUPSC and the UNSC on conflict prevention, the appointment of A3 members as penholders and co-penholders in the UNSC, and the convening of preparatory meetings ahead of council-to-council consultations.

A robust STG agenda matters for the AU–UN partnership from both political and policy perspectives. African leadership in addressing collective peace and security efforts is imperative for the AU’s long-term credibility as a continental institution. But while the AUPSC and the AU Assembly have frequently endorsed the agenda and its goals, there is increasing pressure to demonstrate tangible progress as violence and instability continue to impact many countries.8 UN Secretary-General António Guterres has consistently lauded partnerships with regional organisations as essential for contemporary multilateralism, given that contemporary crises are interconnected with regional and international dynamics.9 Moreover, African peace and security issues continue to feature prominently on the UNSC agenda: in 2019, over 50% of Council meetings and 64% of its outcome documents concerned an issue on the continent.10 These challenges require a collective response, which the UN and AU are best placed to provide.

While the AU and UN have cooperated effectively on a range of conflict prevention and crisis management initiatives in recent years, the AUPSC and the UNSC – increasingly interdependent engines of the partnership –

remain locked in a relationship that is fundamentally unequal in terms of powers, authority, resources and political status. Divergent political interests of their members, different mandates and working methods often limit their ability to reach agreement on the most sensitive files.11 Thus, in spite of stated support for the STG agenda, entrenched political hurdles inhibit more meaningful AU–UN cooperation.

Accordingly, one of the most significant challenges concerns exactly how member states can best translate the STG political declaration into a comprehensive and implementable policy. While the AUMR is a positive step forward, it does not sequence priorities, or explain how particular interventions and processes will achieve the STG agenda’s desired outcomes. The AUMR, therefore, is more valuable as a longer-term roadmap, on which the AU can build closer and more meaningful cooperation with the UN and other sub-regional multilateral actors.

AU–UN Cooperation to Date on the STG Agenda

Over the past two years, Addis Ababa and New York have accelerated momentum to implement various aspects of the STG agenda. This momentum reflects a balance between short-term interventions and longer-term policy processes to translate the agenda into concrete action. Effective implementation of the STG agenda’s conflict prevention and crisis management commitments first requires collective buy-in from all AU member states, which can then be supplemented by the broader UN membership. In this light, the AUPSC is mandated to guide AU member state engagement and provide annual implementation reports of the AUMR to the AU Assembly.12

While there have been efforts to achieve a more uniform approach towards conflict prevention and crisis management among all AU member states, divergent approaches have nonetheless posed a challenge to the overall process, especially in terms of monitoring and reporting on progress. Two issues in particular inform the different perspectives among member states. First, AU member states hold differing views regarding the extent to which the AU Commission should directly engage on specific peace and security initiatives – which impacts the extent to which it can engage on conflict prevention.13 Second, some AU member states have prioritised arms control, DDR and security sector reform (SSR) – practical steps towards silencing guns – that do not necessarily reflect the AUMR’s more holistic approach to conflict prevention.14

The A3 is the AU’s fulcrum for mobilising support for the STG agenda at the UN. These mobilising efforts began during the UNSC and the AUPSC July 2018 meeting and culminated in the unanimous adoption of UNSC Resolution 2457 in February 2019.15 Resolution 2457’s preambular paragraphs reflect the diverse political, governance, legal and socio-economic issues underpinning the AUMR. But while the operative paragraphs encourage closer cooperation between the AU and UN on many issues where they already work together, they do not provide new or concrete commitments for the UNSC to support AU member states or the AUC on these political, governance, legal and socio-economic issues. UNSC members continue to debate how much of the resolution’s text constitutes “agreed language” that can be applied to specific country situations, or whether the resolution is solely applicable to thematic agenda items related to “peace and security in Africa” or “cooperation between the UN and the African Union”.16 These efforts demonstrate that political support for the STG agenda does exist, but there is still healthy debate over the AUMR and its conflict prevention agenda. Former and current A3 members will likely sustain international engagement on the STG agenda, with two planned high-level interventions already scheduled for 2020: Equatorial Guinea (which presided over the UNSC when Resolution 2457 was adopted) is scheduled to host a ministerial-level PSC discussion on the AUMR in March 2020, and South Africa (a current A3 member) is planning to use its 2020 chairship of the AU to convene an extraordinary AU Summit on the STG agenda in May.

At the institutional level, AU–UN cooperation on the STG agenda and on broader conflict prevention efforts are comparatively stronger than similar engagements among their member states. The two organisations engage frequently through established partnership mechanisms between senior leadership and between desk officers.17 Beyond formal partnership structures, day-to-day collaboration routinely occurs throughout many substantive divisions in both headquarters and throughout different field and mission settings. While various institutional and interpersonal dynamics sometimes constrain this cooperation, the commitment and impetus for joint AU and UN engagement is valuable.18

These commitments have helped the organisations rapidly scale up collaborative efforts to support the STG agenda. Multiple AU entities play a role in advancing the STG agenda: the AU Commission chairperson appointed a high representative for the STG agenda in October 2017, and established a technical secretariat housed in the chairperson’s office (which has since moved to the Commission’s Peace and Security Department). Numerous other departments and initiatives by the peace and security commissioner, through his appointment of special envoys, have also undertaken initiatives that fall under the STG banner.

Furthermore, within the AU, this institutional diversity reflects the broad range of tasks within the AUMR and the comparative advantages different entities have: for example, the AU youth envoy’s engagements have sought to not only ensure a prominent youth focus within STG activities, but also to sensitise the agenda among African citizens.19 On the other hand, the multitude of AU Commission focal points and activities convened under the banner of the STG agenda have contributed to a lack of clear institutional ownership, with multiple corresponding lines for monitoring and reporting on progress.

UN support to the STG agenda accelerated after the adoption of UNSC Resolution 2457, which requested the UN secretary-general to provide updates on “implementation measures towards enhancing the support of the United Nations and its agencies to the African Union in the implementation of Vision 2020 to Silence the Guns in Africa”.20 To meet these demands, the UN formed a system-wide task force on the STG agenda, chaired by the assistant secretary-general for Africa in the departments of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs and Peace Operations (DPPA/DPO), to coordinate support to the agenda across 29 departments and agencies.21 The task force set out to identify clear priorities divided according to peace and security, socio-economic and advocacy issues. In terms of conflict prevention and crisis management, many of the UN’s initiatives in support of the STG agenda align with pre-existing areas of AU–UN cooperation, including mediation support, technical assistance on DDR and civilian protection.22 As the task force is only one year old, many of its initial activities are pre-planned activities or in the early stages, but this has also given the UN some leeway to explore initiatives that prioritise a more holistic approach to conflict prevention and AU engagement, as evidenced by new initiatives on youth dialogue and on unarmed civilian protection.23

Opportunities for the AU–UN partnership to sustain the STG agenda beyond 2020

While the AU, UN and their member states are mobilising quickly around the December 2020 milestone, it is clear that these efforts will need to continue well beyond 2020 to get closer to the aspiration of a conflict-free continent. The structural transformation required across many countries to achieve these goals should be measured in decades, not years. Building societies characterised by democratic governance, resilient institutions and inclusive socio-economic development are not merely technical processes; they require sustained political movements and visionary leadership to navigate the inherent, complex trade-offs associated with such monumental changes.24 This is why it is imperative that the AU and UN use the political momentum around this initiative to strengthen their collaboration on conflict prevention and anchor the STG agenda into their future work. Four clear steps can help guide their efforts.

First, as AU–UN interactions often take place in headquarters or across peace operations missions, there is scope for these two institutions to enhance their collaboration in non-peacekeeping or non-peace operation settings.25 A significant portion of prevention-related work is undertaken in countries not yet undergoing political crises or systematic violence and where the UN and the AU do not maintain peace operations or liaison offices. Enhanced collaboration between UN country teams and AU officials – including through more frequent information and analysis sharing, joint messaging by principals and aligned programming activities – can amplify prevention and post-conflict recovery efforts in countries where peace operations are not active.

Second, as an unofficial bridge between the UNSC and the AUPSC, the A3 should continue to champion the STG agenda and provide regular updates of efforts to implement AUMR provisions that will continue beyond 2020. Advocating for more systematic references to Resolution 2457 in Council meetings and outcome documents can encourage more frequent reflection on the commitments contained in the said resolution. Building on the October 2018 Arria-formula discussion about the STG agenda, the A3 can use other tools and processes within the UNSC to focus on the initiative, and on conflict prevention more broadly. The UNSC’s Ad Hoc Working Group on Conflict Prevention and Resolution in Africa (for which an A3 member is always chairperson) has the mandate to discuss prevention-focused issues in addition to AU–UN relations. A3 members can also capitalise on the increasingly frequent consultations between the UNSC and the UN’s Peacebuilding Commission (and between the AUPSC and the Peacebuilding Commission) to provide inputs to the UNSC more concretely on issues related to “conflict prevention, political dialogue, national reconciliation, democratic governance and human rights”.26

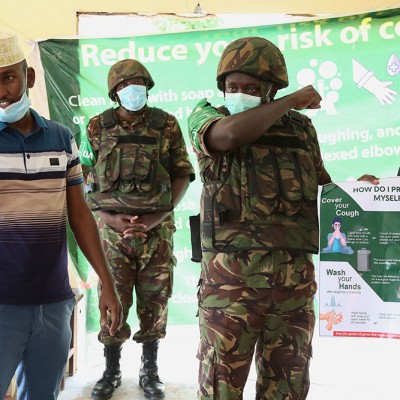

Third, closer programmatic collaboration on emerging prevention priorities represents opportunities for the UN to align its focuses closer to the AU. For example, incorporating regional issues and cross-border dynamics into existing analysis and programming can better prepare the partners to engage in any given situation. Local infrastructures for peace – formal and informal mechanisms that communities use to reduce tensions and build cohesion – can provide valuable complements to conventional conflict prevention and resolution efforts.27 The STG agenda’s holistic approach to prevention aligns strongly with consensus on preventing violent extremism and terrorism, requiring inclusive societies, accountable and impartial security institutions, and a clear understanding of the nexus between local issues and international factors.28

Finally, ongoing reforms and policy reviews at the AU and UN should provide space for more coherence on long-term prevention priorities. The AUC reforms, the creation of a new APSA implementation plan and an emerging review of the AU’s PCRD policies offer clear avenues to integrate the STG agenda’s priorities within existing structures. Similarly, the 2020 Review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture presents an opportunity for African member states to advocate for a more coherent and systematic AU-UN partnership across a range of peacebuilding efforts.29

Conclusion

Sustaining momentum on the STG agenda beyond this year requires the AU and UN to work closely in translating the AUMR’s ambitious goals into more coherent political leadership and policy action. While the agenda covers many diverse areas, more systematic AU–UN cooperation on conflict prevention efforts (from both country-specific and thematic perspectives) represents a concrete way to amplify the partnership. Diversifying how the two organisations engage one another can help the partnership grow even stronger. But political commitment to conflict prevention among member states is a necessary first step on the journey to building peaceful societies. AU member states and the AU Commission face high expectations to achieve their long-term goals of silencing the guns. But given the increasingly global political, security and economic dynamics underpinning conflicts on the continent, a strong partnership with the UN is imperative for working towards a conflict-free Africa.

Daniel Forti is a Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute’s (IPI) Brian Urquhart Center for Peace Operations. His current work focuses on issues related to peace operations and partnerships between the United Nations and the African Union.

Priyal Singh is a Researcher at the Institute for Security Studies’ (ISS) Peace Operations and Peacebuilding programme. His areas of interest include institutional theory and development, particularly on global governance, security and stability.

This article is published as part of a joint project between IPI and ISS on the UN–AU partnership in peace and security. This article is based on their report, ‘Toward a More Effective UN-AU Partnership in Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management’, published in October 2019.

Endnotes

- Forti, Daniel and Singh, Priyal (2019) ‘Toward a More Effective UN-AU Partnership in Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management’, Available at: <https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1910_UN-AU_Partnership-1.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- United Nations and African Union (2017a) ‘Joint United Nations–African Union Framework for Enhanced Partnership in Peace and Security’, Available at: <https://unoau.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/signed_joint_framework.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- United Nations and African Union (2018) ‘AU–UN Framework on Implementation of Agenda 2063 and Agenda 2030’, Available at: <https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/au-un-implementation-framework-for-a2063-and-a2030_web_en.pdf> [Accessed 16 March 2020].

- African Union (2013) ‘50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36205-doc-50th_anniversary_solemn_declaration_en.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- African Union (2016) ‘African Union Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by Year 2020 (Lusaka Master Roadmap 2016)’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/37996-doc-au_roadmap_silencing_guns_2020.pdf.en_.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- Ibid.

- United Nations (2019a) ‘Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc. A/73/890 – S/2019/448, 30 May, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/448>, Para. 8 [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- Dersso, Solomon (2020) To Really Silence the Guns, the AU’s Resolve Must be Stronger. Mail & Guardian, 5 February.

- See: Guterres, António (2017a) ‘Remarks to the UN Security Council Open Debate on “Maintenance of International Peace and Security: Conflict Prevention and Sustaining Peace”’, New York, 10 January, Available at: www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2017-01-10/secretary-generals-remarks-maintenance-international-peace-and; and Guterres, António (2017b) ‘Secretary-General’s Remarks to the African Union Summit [as Delivered]’, Addis Ababa, 30 January, Available at: <https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2017-01-30/secretary-general%E2%80%99s-remarks-african-union-summit-delivered> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- United Nations (2019b) ‘Highlights of Security Council Practice 2019’, Available at: <https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/highlights-2019> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- Ibid.

- African Union (2017a) ‘Decisions, Declarations, Resolution and Motion’, Assembly/AU/Dec.630(XXVIII), 28th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union, 30-31 January, Addis Ababa, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/32520-sc19553_e_original_-_assembly_decisions_621-641_-_xxviii.pdf> [Accessed 11 March 2020].

- Forti, D. and Singh, P. (2019), op. cit., pp. 19–20.

- African Union (2017b) ‘Decisions, Declarations and Resolution’, Assembly/AU/Dec.645(XXIX), 29th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union, 3-4 July, Addis Ababa, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/37294-assembly_au_dec_642_-_664_xxix_e_1.pdf>; and African Union (2019) ‘The AU Peace and Security Council Open Session on the Progress Made in the Implementation of the AU Master Roadmap of Practical Steps for Silencing the Guns in Africa by the Year 2020, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/the-au-peace-and-security-council-open-session-on-the-progress-made-in-the-implementation-of-the-au-master-roadmap-of-practical-steps-for-silencing-the-guns-in-africa-by-the-year-2020> [Accessed 11 March 2020].

- The draft resolution was endorsed by 77 UN member states (including 27 African countries) – see: United Nations Security Council (2019a) ‘Draft Resolution, UN Doc. S/2019/179’, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/179> [Accessed

11 March 2020]. - Recent resolutions on the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) are the only country- or mission-specific outcome documents that contain operative references to Resolution 2457 (see S/RES 2463, Para. 16 and S/RES/2502, Para. 16). All other UNSC references to the resolution have come in thematic debates.

- These include the UN–AU Annual Conference, the Joint Task Force on Peace and Security and the Consultative Meeting on the Prevention, Management and Resolution of Conflicts (i.e. the annual Desk-to-Desk meeting). For more information, see: Forti, D. and Singh, P. (2019) op. cit., pp. 14–18.

- Forti, D. and Singh, P. (2019) op. cit., pp. 18–20.

- African Union Youth Envoy (2020) ‘Survey on Silencing the Guns’, Available at: <https://auyouthenvoy.org/stgsurvey/> [Accessed 11 March 2020].

- United Nations Security Council (2019b) Resolution 2457.

27 February, Paragraph 22. - The task force includes 29 UN agencies, departments and field offices. See: United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (2020) ‘UN Support to the AU Initiative on Silencing the Guns in Africa’, Available at: <https://dppa.un.org/en/un-support-to-au-initiative-silencing-guns-africa> [Accessed 11 March 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See the remarks by Vasu Gounden in United Nations Security Council (2019b) op. cit.

- For a full list of areas where the two organisations engage in country, see: Forti, D. and Singh, P. (2019) op. cit., p. 22.

- United Nations and African Union (2017b) ‘Joint Communique on United Nations–African Union Memorandum of Understanding on Peacebuilding’, 18 September, Available at: <https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/documents/joint.com_.au-un-9-19-2017.pdf.

- Lamamra, Ramtane (2020) ‘Remarks to the 33rd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union on the Implementation of the AU Flagship Project on Silencing the Guns within the Context of the AU Theme for 2020’, 9 February, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/speeches/38101-sp-remarks-au-high_rep_silencingguns9_2_2020.pdf> [Accessed 11 March 2020].

- See the remarks of Ambassador Fatima Mohammed at: United Nations Security Council (2020) ‘Provisional Record of the 8743rd Meeting of the United Nations Security Council: Peace and Security in Africa’, 11 March, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/S/PV.8743> [Accessed 16 March 2020].

- United Nations Peacebuilding Commission (2020) ‘2020 Review of the Peacebuilding Architecture: Proposal for Suggested Terms of Reference’, Available at: <https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/documents/suggested_tors_for_the_2020_review_-_final1.pdf> [Accessed 11 March 2020].