Introduction

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)/African Union (AU) in 2013, African leaders solemnly declared “not to bequeath the burden of conflicts to the next generation of Africans” and “to end all wars in Africa by 2020”.1 The AU Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want,2 adopted two years later under the aspirational goal of an “integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens”, reaffirmed that “all guns will be silent by 2020”, meaning that Africa “shall be free from armed conflict, terrorism, extremism, intolerance and gender-based violence, which are major threats to human security, peace and development”. The AU Agenda 2063 rightly recognised that good governance, democracy, social inclusion, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law are the “necessary pre-conditions for a peaceful and conflict free continent”. The framers of this document were keenly aware – as many others are – that without addressing the pervasive, internal democratic, governance and development deficits at the root of much of the violence on the continent, sustainable peace would, at best, be elusive.3

Sadly, nearly absent from these and other documents – including the 2016 master roadmap of practical steps to silence the guns4 – is the word “leadership”. The few times that transformational leadership is mentioned in Agenda 2063, it tends to refer to actions of individual political leaders, without reference to how it should be developed or exercised.

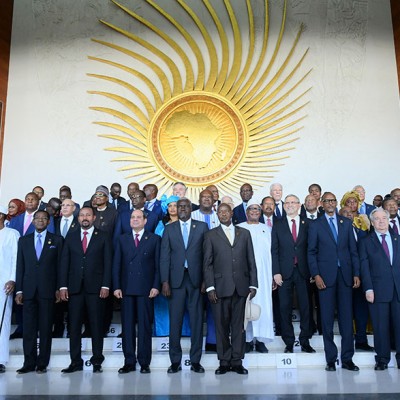

At the last AU Summit (9–10 February 2020), held under the banner of “Silencing the Guns: Creating Conducive Conditions for Africa’s Development”, some refreshing leadership moments were on display. The highlight was the acceptance statement of President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa5 as the new AU chairperson for 2020. The statement articulated a clear, compelling and forward-looking agenda for change. Noteworthy were the two extraordinary summits the president planned to convene back to back in May 2020 to make advances on the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and on the bedevilling conundrum of silencing the guns. Equally noteworthy were the actions he announced to achieve greater women’s political and economic empowerment and to unleash the leadership potential and contributions of Africa’s digital natives – the youth.

Leadership is not just about the leaders

Although political leaders bear the primary responsibility for shepherding the silencing of the guns’ vision towards its desired ends, they cannot do it alone. Leadership for peace is not the preserve of governments or of individuals in formal positions of authority, divorced from the actions of the people who also exercise leadership outside the formal realm.

So then, what kind of leadership are we talking about? How should such leadership be understood, framed and exercised if it is to have a path-breaking influence on silencing the guns and taming the causes that drive people to use them? How can the energy of the critical mass of Africa’s 21st century change agents and trailblazers,6 who are fiercely and fearlessly leading throughout the continent, be further harnessed and nurtured? Specifically, what additional policies and initiatives can be realistically envisaged at the national and continental levels to unlock the transformative potential of these agents and of the change agenda announced at the February 2020 summit?

This article will attempt to provide elements of a response to these questions, with only some references to the rich and varied literature on leadership7 and the powerful assumptions that have long made us believe that leadership is only about the leader. In a world increasingly changing from below, the anachronism of such a view is glaringly evident. We live in a time where followers and context have become a far bigger part of the conversation than the leaders themselves, with technology ceaselessly disrupting the long-standing patterns of dominance and the traditional deference to authority.

Leadership for silencing the guns and sustaining peace

Before addressing the first question, it is important to put to rest any lingering illusion that only if the guns are silenced, sustainable peace will reign. While violent conflicts remain one of the biggest challenges facing Africa, these conflicts have not started just because arms have been available. Peace scientists who have studied the factors associated with sustainably peaceful societies have shown that addressing the underlying drivers and accelerators of violence, while necessary, are insufficient to restore and foster peace for the long haul.8 These efforts need to be complemented by the equally important endeavour of uncovering and strengthening the resilient capacities that enable societies to manage conflict non-violently, remain peaceful and even prosper.

Sustainable peace, they contend, has a greater chance to materialise if peacebuilders, policymakers and practitioners build on what people know and what they have achieved. Focusing solely on the causes of conflict9 and its consequences would produce only “half the peace”10 or a highly reversible “negative peace”, requiring often robust or militarised efforts to maintain it.11

In light of the foregoing and for the purpose of this article, I define leadership for silencing the guns and sustaining peace12 as the processes that create and nurture an empowering environment which unleashes the positive energy and leadership potential of people at all levels of society towards a worthy goal they helped to formulate. This entails, among other actions, the creation of participatory and inclusive mechanisms that allow citizens – in particular, women and youth – to articulate challenges to their human dignity and to actively participate in designing innovative and sustainable solutions to those challenges, building on what they have already achieved out of necessity or opportunity.

In defining leadership as a process, I draw upon recent developments of leadership research13 that emphasise practices and interactions which enable leadership to emerge from any level of society in response to a common predicament.14 This definition does not delegitimise person- or position-based leadership. But given that leadership, as mentioned above, does not reside in a person, the role of the individual leader is to unleash the ambitions and aspirations of others who serve the interests and needs of the wider society. In this regard, attuned leadership based on the African humanism of ubuntu,15 if properly harnessed, may serve as a guide.16

So, what kind of actions can be contemplated at the national and continental levels under this process-driven, umbrella framework that could contribute to silencing the guns and sustaining peace?

At the National Level

National governments can use legislative tools to amplify existing pockets of leadership in the governance and economic spheres. Some African countries have already taken valuable steps that can be emulated over the coming years.

One possible next step would be for as many African countries as possible to have their legislatures pass a startup act, following the examples of Tunisia17 and, most recently, Senegal18, with the aim of promoting innovation and entrepreneurship and enabling local startups to overcome constraints and thrive. I am amazed, for example, by the growing number of male and female millennial, high-tech farmers on the continent,19 who are unlocking the power of sustainable agriculture as a job creation engine for youth, while at the same time helping Africa meet its future food security needs20 and making a profit.

What does this have to do with silencing the guns and sustaining peace, one might ask? Think of the armies of unemployed young people who wreak vengeance on societies they believe have turned their backs on them. This is more evident in rich African countries that seem bent on manufacturing poverty, compelling marginalised and frustrated populations who lost faith in their governments to trust nothing but the guns.21

Leadership, in this instance, means harnessing what already exists, and creating the financial and legal incentives that would enable African small and medium enterprises to push the frontiers of digitalisation and innovation and attract commercial investors22 so they can grow and prosper – and, in turn, contribute to “silencing unemployment”.23 Passing startup legislation is a good starting point for scaling up impact.24 It might even help get Africa a step closer to the vision of a startup continent.25

Another area that could benefit from a process leadership approach at the national level is the promotion of peace as a public good, as an explicit, deliberate policy objective, deserving attention at the highest levels of government and commanding the necessary infrastructure and resources.26 Such an endeavour could take the form of a governmental entity, such as a ministry or a department of peace, whose primary mission would be to create and promote a culture of peace and enlarge the “toolbox” of resources at the disposal of governments for dealing with both internal and external conflicts without resorting to the use of force. This could include mapping the local capacities for peace, creating a supportive environment for local civil society organisations engaged in peacebuilding and peacemaking, and promoting intercommunity and cross-border economic incentives for peace. The mission would vary, of course, depending on the context. For countries coming out of conflict that have found their path to peace through an internationally or regionally brokered agreement or a national covenant, such a ministry would also be entrusted with overseeing the implementation of such an agreement. And if this proposition sounds like a fool’s errand, one should take a look at South Sudan and its Ministry of Peace Building, a structure tasked with the implementation of key elements of the revitalised South Sudan Peace Agreement signed in September 2018.27 In October 2018, Ethiopia established its own Ministry of Peace.28 Such structures while may not always fulfil expectations, as the case of the ongoing strife in Ethiopia painfully demonstrates, their establishment should nonetheless be strongly encouraged. This would be consistent with the 2016 UN General Assembly declaration on the right to peace, calling on states to guarantee “freedom from fear and want as a means to build peace within and between states”.29

The creation of ministries of peace would also be in line with the campaign of a Global Alliance, supported by Costa Rica (which has its own ministry of justice and peace),30 calling for the establishment of governmental ministries and departments of peace all around the world.

At the Continental Level

One of the hallmarks of process leadership is to challenge dominant paradigms and shift patterns of thinking, knowing and doing that tend to prescribe predetermined pathways of addressing challenges. One of these paradigms is the way we view the world – as a place with problems to be prevented or a place with opportunities to be seized. “Because problems are usually experienced as threats and instil fears, they tend to be prioritised over opportunities in human decision making”.31 Silencing the guns is neatly ensconced in the problem category. Our fixation with it prevents us from uncovering and appreciating what is going well in Africa, where peace in many nations is the norm, not the exception. Such a fixation also tends to feed the negative narratives associated with the continent.

The 2019 Global Peace Index32 and the Positive Peace Index of the same year33 have shown quite a number of these nations performing relatively well on the peace continuum, outflanking some established democracies.34

In light of the above observations, I propose the organising of an African symposium of peaceful nations in the margins of next year’s ordinary AU summit or the one after, during which self-selected and invited participants from these nations and the region will be asked to share their country’s trajectory to peace, and highlight both the formal and informal institutionalised national structures they have devised or leveraged to sustain it. Using the methodology of appreciative inquiry,35 the ultimate aim of the event will be to learn from these societies’ relative success in promoting peace at home and abroad, and to identify the leadership, governance and development opportunities that the next generation of African leaders could seize upon to further strengthen peace on the continent.

The first and only time such a symposium has been organised at a global level was by the Peacebuilding Alliance in 2009 in Washington, DC, where 18 countries representing various regions in the world gathered for three days to share their peace stories and learn from each other. Botswana and Malawi were among these countries.36

The proposed African symposium could be preceded by a series of regional workshops, using the same approach and aiming for the same objectives. The outcomes of these workshops could feed into those of the symposium. Should the idea find favour, the conception and organisation of the workshops and the symposium could be entrusted to an independent African think tank such as ACCORD, with proven thought leadership and convening capabilities and expertise. Such events could help advance ACCORD’s Global Peace initiative, which is designed to build bridges between peace, governance and development.37

Concluding thoughts

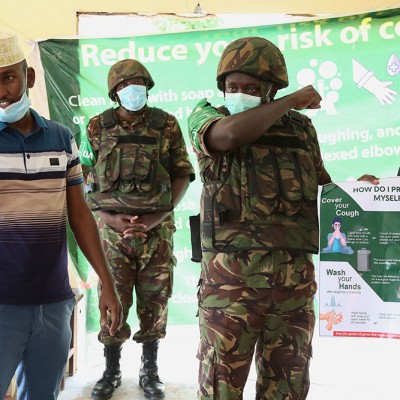

At the time of writing (March 2020), humanity is facing an unprecedented crisis due to the coronavirus pandemic. It has spread fear and seems to have sucked the oxygen out of meaningful international cooperation, as each nation turns inwards to fend for itself and its people. If the virus continues its macabre advance unchecked, it will have a devastating impact on the vulnerable and impoverished populations living in or displaced by violent conflicts on the African continent, where social distancing to slow down the spread of the disease is a privilege only few can afford. And if urgent action is not taken to “silence the guns”, these populations, surviving in overcrowded camps, could become massive breeding grounds for the virus, overwhelming weak if not broken health systems and exacerbating an already dire humanitarian situation. It is my hope that the roadmap announced by President Ramaphosa, the AU chairperson, and some of the actions proposed above will still be relevant and even implemented despite peace and security setbacks and the unprecedented disruptions and hardships imposed on the continent by the pandemic.

Nothing concentrates the mind more than a crisis.

And it is in times of a global health crisis, in particular, that the mettle of leadership is forged. There is no shortage of such leadership, particularly among youth, on the African continent. It just needs to be harnessed in a timely and courageous manner for the causes of peace, while helping societies navigate the dark paths of the pandemic.

Youssef Mahmoud is Senior Advisor at the International Peace Institute in New York, supporting the sustaining peace and peace operations programmes. He is a former UN Under-Secretary-General who has headed peace operations in Burundi, the Central African Republic and Chad.

Endnotes

- African Union (2013) ‘50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration’, 13 June, Available at: <https://au.int/en/documents/20130613/50th-anniversary-solemn-declaration-2013>.

- African Union Commission (2015) ‘Agenda 2063: The Africa we Want’ (Popular Version), Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36204-doc-agenda2063_popular_version_en.pdf>.

- Khadiagala, Gilbert .M. (2015) Silencing the Guns: Strengthening Governance to Prevent, Manage, and Resolve Conflicts in Africa. New York: International Peace Institute.

- African Union (2016) ‘African Union Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by Year 2020 (Lusaka Master Roadmap 2016)’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/37996-doc-au_roadmap_silencing_guns_2020.pdf.en_.pdf>.

- Ramaphosa, Cyril. (2020) ‘Acceptance Statement by South African President H.E. Cyril Ramaphosa on Assuming the Chair of the African Union for 2020’, 33rd Session of the African Union Assembly, 9 February, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/speeches/38086-sp-au_acceptance_statement-english.pdf>.

- Chironga, Mutsa., Desvaux, Georges. and Leke, Acha. (2019) ‘Leadership Lessons from Africa’s Trail Blazers’, McKinsey Quarterly, 10 January, Available at: <https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/leadership-lessons-from-africas-trailblazers>.

- Northouse, Peter G. (2013) Leadership. London: SAGE Publications. Inc.

- Coleman, Peter.Thomas. (2016) The Essence of Peace? Toward a Comprehensive and Parsimonious Model of Sustainable Peace. In Brauch, H., Oswald Spring, Ú., Grin, J. and Scheffran, J. (eds) Handbook on Sustainability Transition and Sustainable Peace. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, Vol. 10. Switzerland: Springer International Publications.

- Hewko, John. (2016) ‘What is Positive Peace?’, Available at: <https://medium.com/@JohnHewko/what-is-positive-peace-6c558f25247f>.

- Coleman, Peter. (2018) Half the Peace: The Fear Challenge and the Case for Promoting Peace. IPI Global Observatory. New York: International Peace Institute

- Pilling, David. and Barber, Lionel. (2019) ‘Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed: Africa’s new Talisman’, Financial Times, 20 February 2019.

- Mahmoud, Youssuef. (2019) What Type of Leadership does Sustaining Peace Require? IPI Global Observatory. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Olonisakin, Funmi. (2017) Towards Re-Conceptualising Leadership for Sustainable Peace. Leadership and Developing Societies, 2(1), pp. 1–30.

- Crevani, Lucia., Lindgren, Monica. and Packendorff, Johann. (2010) Leadership, Not Leaders: On the Study of Leadership as Practices and Interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26(1), pp. 77–86.

- As a world view, ubuntu broadly means that “together we are one”. It asserts that the common ground of humanity is greater and more enduring than the differences dividing us.

- Khoza, Reuel. J. (2011) Attuned Leadership: African Humanism as Compass. South Africa: Penguin Books.

- Dahir, Abdi Latif. and Kazeem, Yomi. (2018) ‘Tunisia’s “Startup Act” could show other African governments how to support tech ecosystems’, Quartz Africa, 16 April, Available at: <https://qz.com/africa/1252113/tunisia-startup-act-to-boost-african-tech-ecosystem-and-innovation/>.

- Jackson, Tom. (2019) ‘Senegal Becomes 2nd African Nation to Pass Startup Act’, Disrupt Africa, 30 December, Available at: <https://disrupt-africa.com/2019/12/senegal-becomes-2nd-african-nation-to-pass-startup-act/>.

- AFP (2019) ‘Smart tech the new tool for African farmers’, Egypt Independent, 4 May, Available at: <https://egyptindependent.com/smart-tech-the-new-tool-for-african-farmers/>.

- Brooks, David. (2016) ‘The Governing Cancer of our Time’, The New York Times, 26 February, Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/26/opinion/the-governing-cancer-of-our-time.html?_r=0>.

- Assogbavi, Désiré. (2020) ‘Can African Leaders Silence the Guns in 2020 as Promised? 7 Unavoidable Prerequisites’, Ethiopian Monitor, 2 February, Available at: <https://ethiopianmonitor.com/2020/02/02/can-african-leaders-silence-the-guns-in-2020-as-promised/>.

- Wan, Tony. (2017) ‘Why the World’s Youngest Continent Got an Edtech Accelerator’, EdSurge, 10 October, Available at: <https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-10-10-why-the-world-s-youngest-continent-got-an-edtech-accelerator.

- Ikhuoria, Edwin. (2020) ‘Africa: “Silencing the Guns” Means Silencing Youth Unemployment’, allAfrica, 10 February, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/202002100769.html>.

- Okondo Nwuneli, Ndidi (2016) Social Innovations in Africa: A Practical Guide for Scaling Impact. London: Routledge.

- StartUp Maroc (n.d.) ‘StartUp Africa Summit: 3rd Edition’, Available at: <https://www.startupafricasummit.global/>.

- Mahmoud, Youssef. (2017), ‘Sustaining Peace: What does it Mean in Practice?’, IPI Global Observatory. New York: International Peace Institute.

- <https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Government-Organization/Ministry-of-Peace-Building-Republic-of-South-Sudan-100594478325701/>

- No author (2018) ‘Newly Formed Ministry of Peace Aims to Enhance Cherished Values of Peace among Public’, Ethiopian News Agency (ENA), 16 October, Available at: <https://www.ena.et/en/?p=372628>

- United Nations General Assembly (2017) ‘Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 19 December 2016 [on the Report of the Third Committee (A/71/484/Add.2)], A/RES/71/189, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/71/189>.

- The Peace Alliance (n.d.) ‘Global Alliance for Ministries and Infrastructures for Peace’, Available at: <https://p eacealliance.org/global-alliance-for-ministries-and-infrastructures-for-peace/>.

- Coleman, Peter. (2018) op. cit.

- Vision of Humanity (n.d.) ‘Global Peace Index 2019’, Available at: <http://visionofhumanity.org/indexes/global-peace-index/>.

- Institute for Economics & Peace (2019) ‘Positive Peace Report 2019: Analysing the Factors that Sustain Peace’, Available at: <http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2019/10/PPR-2019-web.pdf>.

- Akwasi, Kofi. (2019) ‘Ghana is position 4 in Africa by 2019 Global Peace Index’, MSN Africa, 23 June, Available at: <https://www.msn.com/en-xl/africa/ghana/ghana-is-position-4-in-africa-by-2019-global-peace-index/ar-AADgGQb>.

- Appreciative inquiry is an approach that encourages a shift from fixing “what’s wrong” – a deficit-based approach – towards understanding what is working in human systems – a “what’s strong” approach – and building on those strengths.

- Allen Nan, S., Fisher, Joshua., Yamin, Saira., Druckman, Daniel., Olsen, Danielle. and Ersoy, Meltem. (2009) ‘Peaceful Nations: The Official Report of the Global Symposium of Peaceful Nations’, Available at: <https://allianceforpeacebuilding.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/PeacefulNationsReportFeb19.pdf>.

- ACCORD (n.d.) ‘Global Peace and JCI Partner to Mobilise Youth to Create Change’, Available at: <https://accord.org.za/Global-Peace/>.