Introduction

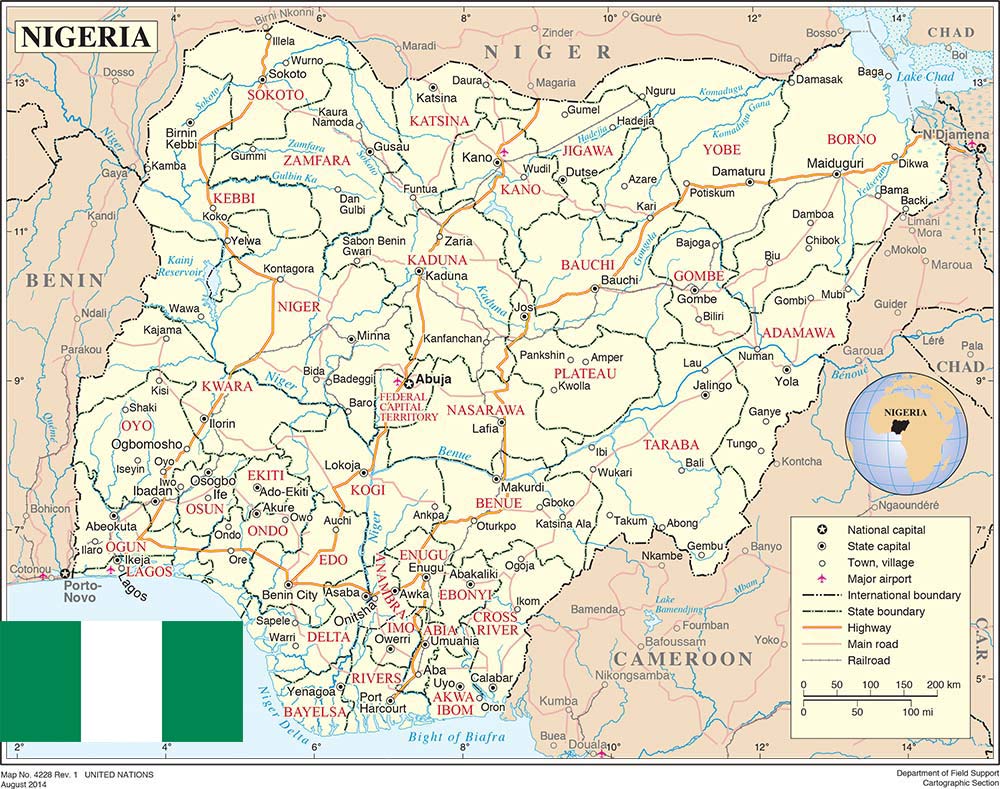

This article analyses the findings from field research, conducted in north-eastern Nigeria in late 2017, which explored the repatriation and reconciliation needs of the communities displaced by Boko Haram’s armed insurgency and the military operations that followed. Major findings include the displaced communities’ diverse contested outlooks on forgiveness, coexistence, physical separation and extermination, with respect to how they would like to interact with rehabilitated former Boko Haram foot soldiers wishing to return home. A secondary focus of this article is to explore how to develop practical and sustainable mechanisms of government–civil society collaboration capable of building the trust and security necessary for repatriation and reconciliation. To establish an informed basis for analysing these two issues, a brief introduction to the regional context is in order.

Regional and Social Context

Boko Haram – or “Western education is prohibited” in Hausa – is a religious-inspired insurgency movement based in north-eastern Nigeria.1 Its campaign of violence against Nigerian law-enforcement personnel and establishments started in 2009 in Borno State and Yobe State. The geographic scope and nature of the targets expanded exponentially in subsequent years. Boko Haram’s attacks, and the government’s counter-offensives, have since killed tens of thousands of people on all sides. Moreover, as of October 2017, some 1.6 million people remain displaced across three of the most conflict-affected north-eastern Nigerian states: Adamawa, Borno and Yobe.2

Under the leadership of presidents Goodluck Jonathan (2010–2015) and Muhammadu Buhari (2015–current), the Nigerian military and police have led an all-out campaign to drive Boko Haram fighters out of their strongholds and hideouts. Local vigilante groups fought side by side with the government forces and played an essential role in intelligence-sharing, combat missions and stabilisation support. As of early 2018, population centres in north-eastern Nigeria once controlled by Boko Haram are mostly clear of its active presence. Relative calm has been restored in these places and normal day-to-day activities have resumed. With these military gains, the Nigerian government and international agencies are terminating the crisis and emergency phase of their activities and refocusing their resources and programmes on stabilisation, repatriation and reconstruction. However, low-intensity fighting, guerrilla-style attacks and security incidents caused by dispersed Boko Haram fighters, including female suicide bombers, still take place in isolated pockets of resistance. Importantly, many rural areas outside the government-controlled population centres remain insecure, because of the sustained presence and infiltration of Boko Haram fighters.

The significant military gains and the return of relative calm present a unique challenge to the long-term efforts and collective self-reflections necessary to decisively tackle the three interconnected roots of the acute crisis that found its distinct expression in the form of Boko Haram’s armed insurgency. The first of these roots is dysfunctional governance. At the heart of this systemic problem is the need to establish inclusive, accountable and efficient mechanisms of governance, capable of making and implementing policies at the federal, state and local level. Importantly, improvement in governance must pave the way for the effective delivery of law enforcement and justice. The second root cause is underdevelopment. The core challenge in this area is how to secure and allocate development resources equitably so as to uplift the rural and urban poor; how to provide education, health services and basic infrastructure universally; and how to create sufficient employment, especially for the growing population of unemployed youth. The third issue is identity crisis. At its very core, this crisis is about how the socio-economically deprived, politically marginalised and religiously misinformed population, especially the youth, can establish self-esteem and positive future outlooks.

Importantly, neither Boko Haram’s armed insurgency nor the government’s counter-offensives have helped resolve these underlying crises. Instead, the campaigns of violence – however important for their respective causes – deepened the existing crises by depriving Nigerian society’s existing resources and capacities of governance reform, development and psychosocial healing. Yet, one may choose to view a decade of destruction and suffering in north-eastern Nigeria as a wake-up call for Nigeria, its neighbours in the Lake Chad region and the international community at large to make a fresh start. Viewed from such a historical perspective, the task of repatriation and reconciliation in north-eastern Nigeria is an unprecedented opportunity for the country to generate political will and social conditions for resolving the three underlying crises. It is within this broad historical context and sensitised awareness that conflict-affected Nigerian communities’ needs for repatriation and reconciliation must be analysed.

Findings: Diverse Outlooks on Repatriation and Reconciliation

Six focus group meetings with internally displaced persons (IDPs) of diverse regional and ethnic backgrounds from Borno State were held in Maidiguri in November 2017. The participants in these meetings were all Muslims. A set of two gender-specific meetings – one for women and the other for men – was held at each of the two government-sponsored formal camps. The remaining two meetings – one for women and the other for men – were held in an informal IDP settlement, which is outside government control and hosted by a local community. These six focus group meetings aimed to: (1) learn about the IDPs’ views on necessary conditions for their future repatriation; and (2) explore their outlooks on the nature of relationships they would like to build with demobilised and rehabilitated members of Boko Haram in their home communities. The gender-specific method of inquiry was intended to ensure each gender-specific group’s independent expression of opinion. A total of 130 IDPs from diverse regional and ethnolinguistic backgrounds participated in the meetings, which had 22 participants on average per meeting. The language used in the meetings was either Hausa or Kanuri or both, depending on the participants’ needs. Interpretation in Hausa and Kanuri was provided by local humanitarian assistance professionals with whom the meeting participants were already familiar.

The method of data collection consisted of first asking open-ended questions about conditions under which these IDPs would like to return home, and then asking them to raise their hands in support of or opposition to a set of propositions presented by the researcher. In response to the open-ended question, “What are the most important conditions under which you will be willing to return home?”, the most frequently observed responses across the three locations were:

- security assurances – some respondents elaborated on their security needs by requesting a sustained conspicuous presence of the military and/or well-disciplined vigilante groups;

- shelter;

- means of livelihood including agricultural instruments, fishing nets and shops for petty trade;

- schools;

- health clinics; and

- basic infrastructure in general.

Asked to name specific leaders and organisations whose public announcements on the presence of adequate security are deemed most credible, many respondents identified village heads, senior traditional leaders (known as emirs in northern Nigeria), and the military and other authoritative government agencies. Some of the IDPs from Bama, a local government area severely affected by violence, explicitly mentioned that they would know the presence of adequate security when their revered king returns to his palace and sits there.

Building on the respondents’ feedback on these open-ended questions, the researcher listed four possible conditions, the fulfilment of which may help the IDPs feel safe enough to live in the same geographic areas as demobilised and rehabilitated Boko Haram members. More specifically, the researcher asked the respondents to raise their hands to indicate whether they would consider the fulfilment of the four conditions as a sufficient reason to coexist (that is, to live in the same geographic area with or without daily contact) with those who previously fought as Boko Haram members. The four suggested conditions are:

- disarmament of Boko Haram members and the seizing of their weapons;

- their explicit commitment to a renunciation of force;

- their confessions of their crimes and their expressed desire for forgiveness; and

- their completion of a government-sponsored rehabilitation programme.

The proposal of these four conditions stems from the researcher’s previous fieldwork and training experience in north-eastern Nigeria.3 It is also informed by the researcher’s cumulative experience in diverse conflict-affected societies.

After asking about the respondents’ willingness to coexist with demobilised Boko Haram members under these four conditions, the researcher then asked them whether they would be willing to forgive former Boko Haram members who have met these conditions. The participants’ responses are summarised as follows:

Table 1: IDPs’ views on conditions for coexistence with former Boko Haram members and for forgiveness

| IDPs’ regions of origin | Male | Female | |||

| Yes to coexistence | Yes to forgiveness | Yes to coexistence | Yes to forgiveness | ||

| Formal Camp 1

(N=55) |

Majority from Mafa; some from Bama and Konduga | 60%

(N=30) |

(This question, unavailable at this point, was not asked in the meeting) | 95%

(N=25) |

95%

(N=25) |

| Formal Camp 2

(N=30) |

Mostly from Bama and Kukawa | 90%

(N=12) |

100%

(N=12) |

90%

(N=18) |

95%

(N=18) |

| Informal Settlement

(N=40) |

Majority from Konduga; some from Gwoza and Bama | 0%

(N=20) 75% (15) stated no to coexistence 25% (5) abstained |

100%

(N=20) 90% (18) demanded separation from Boko Haram as another requirement |

0%

(N=20) |

100%

(N=20) 25% (4) demanded separation from Boko Haram as another requirement |

Note: N refers to the number of respondents

At Formal Camp 1 – the first location where the focus group meetings took place – the respondents were asked to consider the first three conditions (disarmament, renunciation of violence, and confession/request for forgiveness) only. The forth condition (rehabilitation), which was not on the initial list of conditions presented at Formal Camp 1, was proposed by focus group participants at Formal Camp 2, the second research site. The fourth condition was then added to the working list. An expanded list of four conditions was presented to the rest of the focus group meetings to learn about IDPs’ repatriation needs more comprehensively.

In the Informal Settlement – which was the third and final site for the inquiry – the respondents requested that the separation and isolation of demobilised Boko Haram members be given full consideration as an alternative to coexistence. (For this reason, separation from Boko Haram as a possible scenario was not discussed in any of the focus group meetings at the two formal camps.)

To learn from a small number of respondents who rejected both coexistence and separation, additional open-ended questions were introduced. The additional questions explored what these respondents wished to see happen in terms of demobilised Boko Haram members in the respondents’ home communities. Follow-up interviews with them revealed their hope to have all the remaining Boko Haram members executed. These respondents explained that their desire to completely exterminate Boko Haram members stemmed from their deep distrust in Boko Haram fighters’ hidden motives. There were only one to three respondents in each of the three male focus groups who expressed options of this nature. Interestingly, there was not a single female respondent who explicitly supported the extermination of Boko Haram members.

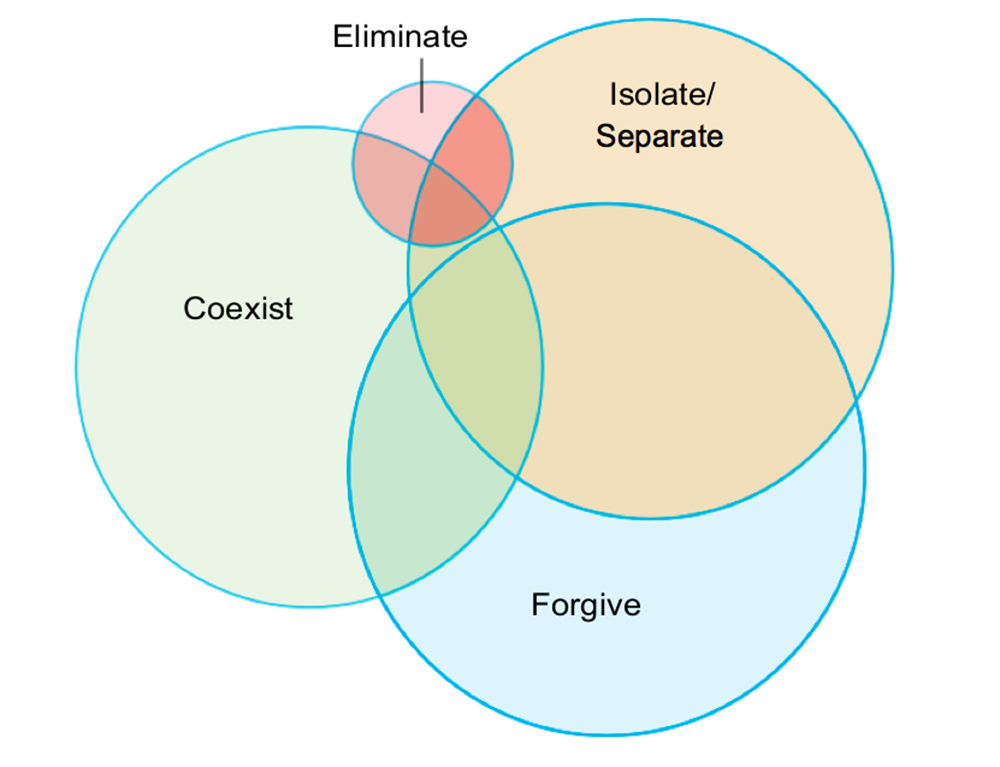

Image 1 summarises these findings. It presents the relative sizes of the selected Maiduguri-based IDP populations favouring one future scenario over the others.

Image 1: Relative sizes of the IDP populations under study favouring one future scenario over the others with respect to their future relationship with demobilised Boko Haram members

Threats to the validity of the research method, as well as the findings of the research, must duly be acknowledged. The small sample size for the research, and a limited geographic and demographic scope of the displaced population under consideration, for example, indicates the tentative nature of the findings. The possibility of tacit peer pressure to follow groupthink in the distinct culture and structure of north-eastern Nigeria’s IDP communities cannot be ruled out, especially when these IDPs respond to a foreign researcher’s questions. Moreover, the reliability of the respondents’ verbal feedback on hypothetical scenarios about potentially life-threatening repatriation decisions as a predictor of their actual choices in real-life circumstances must be considered. Finally, the prevailing norm of masculinity can undermine the female respondents’ freedom to express their views on repatriation when they are brought together with their husbands, fathers and other male decision-makers.

Despite these and other possible limitations, the findings in this study are still evocative and merit serious attention. Importantly, these findings provide a promising basis for more in-depth, systematic research on repatriation that must be undertaken in the near future. To support this vision of future inquiry further, implications of the findings are articulated as follows:

- Many displaced Nigerians of diverse geographic and ethnolinguistic backgrounds are open to coexistence with demobilised and rehabilitated Boko Haram members under well-defined conditions.

- Many of them are also willing to forgive Boko Haram attackers once these conditions have been met.

- Those in favour of exterminating current and former Boko Haram members make up a very small minority of the displaced population under study.

- IDPs with a deep commitment to faith consider forgiveness as a requirement in life. (IDPs’ elaborations on their responses demonstrate their faith-based commitment to forgiveness.)

- Forgiveness inspired by faith is a choice of religious devotees striving to honour God’s will. Victims of violence can therefore forgive their perpetrators in God’s name without accepting the prospect of intercommunal coexistence. This is why it is possible for some of the IDPs to express their willingness to forgive Boko Haram, while simultaneously demanding separation from Boko Haram.

- The implication presented in point 5 is significant, because it highlights the unique worldviews and challenges that inform the distinct nature of reconciliation practices in north-eastern Nigeria. For the purpose of this inquiry, reconciliation refers to a sustained reciprocal process of victim–offender relationship-building. It requires not only forgiveness, but also mutual acceptance. Importantly, forgiveness in the name of God alone falls short of embracing mutual acceptance.

- As illustrated by points 5 and 6, the relationship between the four suggested future scenarios – elimination, separation, coexistence and forgiveness – is highly complex and interconnected. All the male and female respondents from Konduga, for example, categorically rejected the prospect of coexistence, but they nevertheless expressed their willingness to forgive the perpetrators. Moreover, despite their commitment to forgiveness, they requested separation from demobilised Boko Haram members because of their deep distrust in the latter.

It is highly plausible that the communities in north-eastern Nigeria continuously alter their preferences about the four suggested scenarios according to their actual experiences in repatriation, stabilisation and reconstruction. It is also possible that within each community, multiple scenarios are considered, debated, adopted and/or rejected at any given moment. Alternatively, two or more scenarios may be used sequentially in such a way to respond to the evolving dynamics of the community’s psychosocial readiness, its perception and condition of security, and its ability to meet its livelihood needs.

The findings from this inquiry, which build on the researcher’s earlier study, suggest that there are at least seven considerations whose dynamic interplay inform communities’ preferences about which future scenarios they choose to adopt at any given moment. These considerations, which serve as critical determinants in community-based decision-making, are as follows:

- Direct versus indirect experience: Whether the community’s experience of Boko Haram’s attacks is direct, recent and still fresh in its memory, or whether its experience is indirect, secondary and somewhat remote due to the passage of time.4

- Rural versus urban: Whether the community that experienced Boko Haram’s attacks is located in a rural area or an urban centre.5

- Gender: Whether the community members are men or women, considering that the gender difference can critically affect their social experiences in violence.

- Age: Whether the community members are young or old, considering that their ages may correspond to different mindsets – which can, in turn, influence their future outlooks.

- Nomadic north vs agrarian south: Whether the community embodies the traditional nomadic culture of northern Borno State or the modern and/or agrarian culture of southern Borno State.6 (While cultural generalisation and stereotyping must be avoided, the working assumption stated by informed local interviewees is that unlike agrarian culture, nomadic culture tends to express a distinct commitment to honour, remember harm done to in-group members, and seek retaliation. The spread of liberal education in southern Borno reinforces this cultural difference between the north and south.)

- Ethnicity and tribalism: Whether the ethnic and tribal leadership, governance structure and norms of the community favour coexistence over separation, and forgiveness over extermination.

- Level of sensitisation: Whether, and to what extent, the community is sensitised on the sources, effects and responses to Boko Haram’s violence.

An integrated understanding of the four requirements of repatriation, the four future scenarios of community responses and the seven determinants of preferred collective action offers a useful framework of thinking when policymakers, communities and humanitarian agencies make decisions about stabilisation, reconstruction and reconciliation initiatives. Further research is needed to find out how interactions between these factors work in context-specific situations across time and space.

Institutional Mechanisms for Meeting Repatriation and Reconciliation Challenges

To put the proposed framework of coexistence and reconciliation into practice, the Nigerian government and civil society must work together to mobilise political will and resources. The key to broad-based sustainable initiatives for public mobilisation is to activate the existing social practices and mechanisms of conciliation with which Nigerians are already familiar. One way of envisioning such initiatives is for the federal government to formally endorse senior traditional leaders (emirs) to assume leading roles in convening and facilitating broad-based reconciliation dialogues in their respective states, and in the Local Government Areas (LGAs) within each state.7 These traditional leaders can utilise the existing governance mechanisms in which they exercise significant influence. They can support district, village and ward heads working within the existing mechanism of traditional governance to convene and facilitate reconciliation dialogues at the grassroots level. The federal government will need to provide these local leaders with not only an overarching vision and framework of national and regional reconciliation, but also with a sustained commitment to offering resources, mandatory skill-building opportunities and technical advice to ensure programme success. Partnership with trusted religious, political and business leaders, and various other prominent figures in the respective communities, must be established. Moreover, to be truly impactful and sustainable, these reconciliation initiatives must actively promote an inclusive representation of participants from different gender, ethnolinguistic, tribal, religious, age and urban/rural backgrounds.

Finally, a prerequisite to repatriation, reconciliation and reconstruction is security – a requirement mentioned explicitly in all six focus group meetings. Security is necessary not only in conflict-affected population centres and IDP camps, but also in the rural communities to which both IDPs and rehabilitated former Boko Haram members will be returning. Moreover, adequate security must be established along the long, unprotected roads that returnees will need to travel.

A fundamental shift required in future security operations is a planned transition from military-led offensive operations to community-based peacekeeping operations. While the former actively goes after insurgents and fights them, the latter prioritises building zones of security, livelihood and coexistence capable of detecting, deterring and coping with existing and potential security threats. Community-based peacekeeping also relies heavily on the collective will, empowerment and collaboration among local communities and civil society actors committed to actively creating and sustaining conditions for improving security. The military and police will continuously play a significant supportive role in these peacekeeping operations. This is because these operations must still rely on the use of force for law enforcement and self-defence from imminent threats from time to time.

To implement this transition on a large scale, strong political leadership at the highest level is necessary. One way of realising such a major transition is to establish a high-level federal security taskforce comprised of the ministers of Defence, Information and Interior; the inspector general of the police; the military chiefs; and/or other senior officials capable of making or influencing decisions on matters related to national security. Working closely with the president and technical experts, the taskforce can guide the overall planning of the war-to-peace transition, allocate necessary resources and personnel, and support the implementation of the presidential initiative for north-east Nigeria’s reconstruction8 from the defence and security leaders’ perspective.

An essential element of the broad-based transition to peacekeeping is the federal government’s effort to establish a formalised partnership with a broad range of qualified local vigilante groups.9 Such a partnership is essential, because many of the trusted vigilante groups can provide security in unprotected rural areas in which the formal military and police forces can neither establish security nor sustain their presence. In Borno State, an estimated 26 000 vigilantes (as of September 2016) belong to the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), a loosely organised network of homegrown groups that have played an essential role in fighting Boko Haram since its establishment in early 2013.10 The proposed partnership can establish a multiyear agreement between the federal government and qualified vigilante groups. The agreement will need to ensure that qualified vigilantes will regularly receive stipends, equipment and mandatory training, in exchange for the security and peacekeeping services they will need to deliver in designated areas. The training will need to cover human rights and gender norms; well-defined roles of vigilante groups in law enforcement support; best practices in neighbourhood watch and community-based security arrangements; and basic knowledge of repatriation, conflict management and reconciliation. The proposed federal security taskforce can endorse and support this process to enhance its credibility.

Conclusion

The field research conducted in north-eastern Nigeria revealed conflict-affected communities’ diverse perspectives about how to meet reconciliation challenges. Their faith, culture, social experience and various other determining factors will shape and reshape their decisions about whether and how to coexist and reconcile with former insurgents they will encounter upon repatriation. To ensure the success of this transition, formalised government–civil society partnerships must be established to promote reconciliation initiatives and community-based peacekeeping. In turn, these activities must be purposefully designed and implemented to pave the way towards overcoming Nigeria’s long-standing challenges in governance, development and inclusive social identity.

Endnotes

- For a succinct summary of Boko Haram’s rise and expansion, see the introductory section of Arai, Tatsushi (2017) Conflict-sensitive Repatriation: Lessons from North-eastern Nigeria. Conflict Trends, 2017 (1), Available at: <https://accord.org.za/conflict-trends/conflict-sensitive-repatriation/> [Accessed 22 January 2018].

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2017) ‘Nigeria: Humanitarian Dashboard (January-November 2017)’, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/nigeria-humanitarian-dashboard-january-november-2017> [Accessed 22 January 2018].

- Findings from the previous research are reported in Arai (2017) op. cit.

- Arai, Tatsushi (2017) Interview with a Nigerian medical doctor and senior official in Borno State’s Ministry of Health on 21 November. Maiduguri.

- Arai, Tatsushi (2017) Telephone interviews with Nigerian humanitarian support professionals in north-eastern Nigeria on 17 and 18 October.

- Arai, Tatsushi (2017) Interview with a Nigerian humanitarian support professional with a background in anthropology on 21 November. Maiduguri.

- This proposal of reconciliation initiatives, led by traditional leaders, is based primarily on Arai, Tatsushi (2017) Interview with a senior Nigerian civil society leader, Abuja, 25 November.

- The Presidential Committee on the North East Initiative (<https://pcni.gov.ng>) was launched in 2016 to lead the federal government’s effort in the post-conflict recovery and development of the region.

- This recommendation, in broad outline, mirrors that of Ogbozor, Ernest (2016) ‘Understanding the Informal Security Sector in Nigeria’, United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Special Report 391, Available at: <https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR391-Understanding-the-Informal-Security-Sector-in-Nigeria.pdf> [Accessed 22 January 2018].

- The 2016 estimate of the number of CJTF members is based on Jaafar, Mohamed (2016) ‘The Home Guard’, The Economist, 29 September, Available at: <https://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21707958-volunteers-who-helped-beat-back-boko-haram-are-becoming-problem-home> [Accessed 22 January 2018].