Introduction

Little is known about the contribution of nhimbe, an indigenous collaborative work system, in peacebuilding – yet it has boundless potential to promote sustainable peace and community cohesion-building. Nhimbe is an indigenous traditional practice where community members come together to work towards a common goal. In the process of working together, individuals build relationships – they share experiences and develop a sense of family and community. Societal conflicts, tensions and problems are diffused, and some conflicts are resolved as people participate in nhimbes. This article proposes an indigenous conceptual model for peacebuilding using nhimbes, by reviewing how Heal Zimbabwe Trust, a community peacebuilding organisation, utilises nhimbe as a violence prevention and conflict transformation tool. The article demonstrates how nhimbe platforms promote community peace and social cohesion by empowering communities to become tolerant, mend individual and community relations and, ultimately, reconcile their past disputes.

The Traditional Concept of Nhimbe

Nhimbe is a traditional Shona practice of working together as a community to help each other in daily tasks such as harvesting, weeding fields, constructing a house, gathering manure or other tasks. It is “a socialising agent where members of the community come together and communally assist each other in a number of ways”.1 Individuals and families participating in nhimbe promote an African ideal of individuals’ communal responsibility, prevention of selfishness2 and, most importantly, keeping people interacting within communities.3 By nature, a nhimbe caters for community security rather than individual welfare, and it broadly exemplifies a Shona and African culture of extended family, oneness, community, sharing and togetherness. A nhimbe hosted at the traditional leader’s home was largely known as Zunde raMambo, while when hosted by other ordinary members of the community, the nhimbe was called jakwara, jangano or humwe among other Shona dialects. However, the practice of undertaking a common task is not solely peculiar to Zimbabwe. It is also practised in other countries – examples include harambee in Kenya, chilimba in Zambia and milpa in Mexico.4

Existing literature shows that many scholars view nhimbe variously asa work party, communal entertainment and leisure practice5, or a community development model.6 However, early missionaries considered the practice evil because people drank beer at nhimbes.7 Irrespective of different scholarly interpretations, the practice of hosting nhimbes has existed since the 1800s, when community members helped each other to grow crops, weed, harvest and develop water sources, such as small dams and wells. Holleman observes that “every field holder, man or woman would at least host a nhimbe during every season depending on the size of the field and prospects of the season”.8 Households would aim for higher productivity by investing in nhimbes’ pooled labour. Those without oxen would also be helped by community members through nhimbes, if they participated in other members’ nhimbes. Generally, the person or family hosting a nhimbe would brew traditional beer and prepare food, which acted as a mobilising factor for community members. Nhimbes were hosted by village or community members, or by the local traditional leader. As such, nhimbe had multifaceted benefits ranging from improving food security, promoting a sense of community and community responsibility, transforming the moral economy of communities, cutting labour costs and pooling resources for greater efficiency and effectiveness.

However, nhimbe is declining with modernisation, although it is still being practised in rural areas. This may imply a lack of modernity in the nhimbe practice. This view is bolstered by Shutt, who observed that nhimbes were used by squatters to help each other in agricultural activities.9 The decline of the nhimbe practice and its benefits is blamed on the rise of African businessmen, the replacement of chieftainship roles with modern local government structures, work parties, and the general selfishness of the new generation.10 Although declining, the importance of hosting nhimbes – expressed in their capacity to promote togetherness, reciprocity, trust, respect, allegiance and inclusivity – requires an intellectual and practical regeneration of the concept towards building community cohesion. In addition, Muyambo notes that brick moulding and school block construction are modern adaptations of nhimbe practices in rural Zimbabwe.11

Utilising Nhimbe in Contemporary Peacebuilding

To promote political tolerance, prevent violence and address the effects of past gross human rights violations and violence, Heal Zimbabwe Trust has been implementing nhimbes as part of its grassroots peacebuilding activities. Heal Zimbabwe Trust considers nhimbe as a neutral platform where community members can meet to participate in some household or community work without being sensitive to their social, economic or political affiliation. Nhimbes are unifying, and they allow room for community members to start valuing working together. They can help community members build relationships, become tolerant and enhance community security through trust-building, collectivism, loyalty and humanity. Although nhimbes are principally identified with food production, their application to peacebuilding, conflict transformation and violence prevention shows that nhimbes have multiple functions. For example, working together shows community solidarity, while building relationships can translate to community security.

To Heal Zimbabwe Trust, the assumption of hosting a nhimbe is that “if communities implement nhimbes, they will be able to improve individual and group relations” – hence contributing towards improved community cohesion. If communities hosting nhimbes involve diverse stakeholders such as village heads, headmen, chiefs, councillors, church leaders and community-based organisations (CBOs)/faith-based organisations in their activities, then they promote inclusive decision-making processes and build bridges for engagement across different levels of decision-makers and citizens. However, while a nhimbe can be a neutral platform, it can also act as a conflict trigger within communities – especially when the platform is wrongly perceived as a political gathering tool or if it overlooks valuable traditional community protocols, such as failing to involve traditional leaders and authorities who can legitimise its essence in community cohesion.

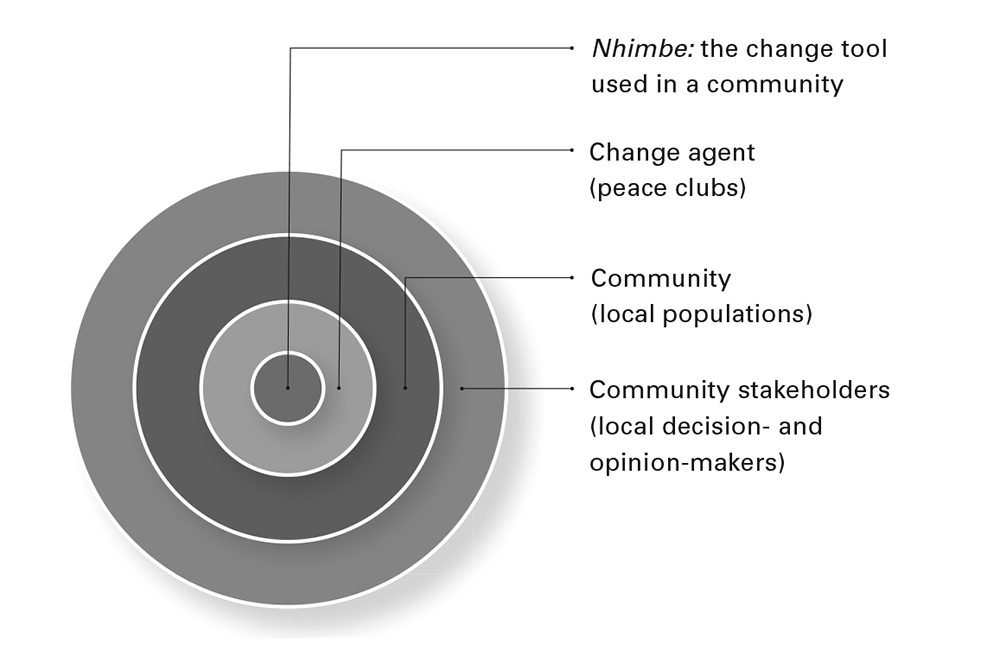

The diagram below outlines the way in which nhimbe is understood by Heal Zimbabwe Trust as a tool for peacebuilding. Nhimbe is the change tool found at the centre, while the first layer represents change agents. These change agents are infrastructures for peace, such as the peace clubs established by Heal Zimbabwe Trust in the communities where it operates. A peace club is a group of local members who come together to promote peaceful social relations, tolerance and non-violent activities in their community. Membership to peace clubs is open to all local community members including traditional leaders, church leaders, women, youth, men, businesspeople, people with disabilities, representatives of CBOs and village health workers. Peace clubs are change agents because they are responsible for organising nhimbes and other peacebuilding activities in communities where they are established.

Figure 1: Nhimbe peacebuilding conceptual model

The second layer represents community members. These are local populations that are invited by peace clubs to participate in nhimbes and other peacebuilding activities. By inviting community members to a nhimbe, the change agents expand their role of building community cohesion among community members and build relationships in the communities where they are established. The peace clubs’ capacity to mobilise community members and stakeholders to participate at nhimbes legitimises their acceptability as a peacebuilding infrastructure in that community.

The third layer represents community stakeholders such as village heads, headmen, chiefs (traditional leaders), church leaders, village and ward development committees and councillors. These stakeholders are decision-makers and influencers within communities, whose support to peace clubs improves the legitimacy and effectiveness of nhimbes as a peacebuilding tool. If the stakeholders disapprove of the holding of any nhimbe or the legitimacy of a peace club, it becomes difficult for the peace clubs to build peace and promote social cohesion. Communities may even be further divided between those in support of the peacebuilding interventions and those against. Therefore, in all cases where nhimbes are organised, peace clubs are upheld to engage both community members and stakeholders without being selective or discriminatory, thus enhancing inclusivity, a culture of consultation and respect for diversity.

A Typical Nhimbe Implementation Process

Peace clubs organise their own nhimbe activities without Heal Zimbabwe Trust taking a leading role. Most nhimbes held include organising clean-up campaigns in public spaces (such as schools, shopping centres and clinics), repairing roads, weeding, harvesting crops or working at any preferred community project. Peace clubs could also organise nhimbes at the homesteads of their members, needy people in their community or upon request by some members of the community or stakeholders. They also target specific homesteads of community members where they have detected conflicts within the family or between families. To increase the buy-in of stakeholders, peace clubs also organise nhimbes at the homesteads of traditional leaders, church leaders and opinion-makers. It is the responsibility of peace club members to mobilise community members and key community stakeholders to participate in planned nhimbes.

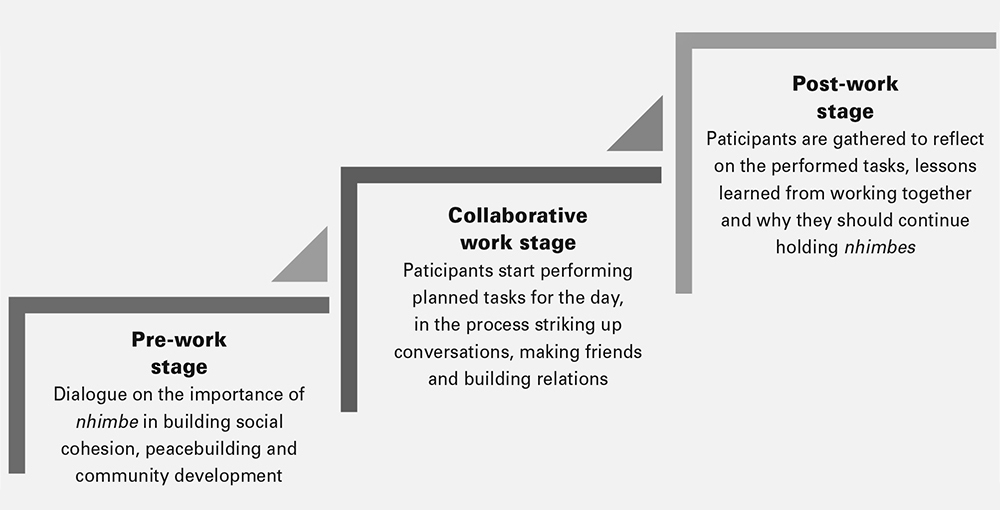

The implementation process of a nhimbe has three stages: the pre-work stage, the collaborative work stage, and the post-work discussions stage.

Figure 2: Nhimbe Activity Process

Pre-work stage: This stage is a short dialogue process that takes place immediately before implementing a nhimbe. Participants are gathered and introduced to the purpose of the nhimbe and the nature of work involved. A peace club member leads by explaining to the participants in attendance: (1) the purpose and structure of the peace club; (2) why they organise nhimbes; and (3) the traditional importance of nhimbes. This allows all participants to get to know each other initially, as well as to recognise the essence of the peace club in their community. Pre-work dialogue creates a shared vision and a unifying position towards building relations through working together.

Collaborative work stage: This stage involves all participants working on the planned tasks. As the work commences, community members consciously work closely with each other, engage in conversations and create relationships. However, peace club members have a responsibility to deliberately set up conflicting parties (if any) to work close to each other, so that they can start conversations and begin building relations. A conversation is unavoidable when conflicting parties are working close to each other. However, setting up conflicting parties to work close to each other requires caution, since some parties could end up escalating their conflict. To avoid such scenarios, the peace club assigns trusted individuals to be attentive to the paired persons. A peace club can consider their pairing successful if conflicting parties are able to strike up a conversation and start dialoguing on their conflict issues. As such, the collaborative work stage is crucial in conflict transformation and building cohesion.

Post-work stage: This last stage comes after the collaborative work process, when the nhimbe participants come together to rest and have lunch or refreshments. During this resting period, a peace club member, community leader or designated facilitator leads a dialogue on what participants learnt from working together, as well as what they liked best or what frustrated them. This session is meant to provide a reflection of the purpose of nhimbes and the value of working together as a community or family.

The three stages of the process are crucial in that each stage has a specific objective that contributes to the broader peacebuilding and social cohesion goal. The first stage conscientises participants about the deliberate purpose of building relationships and improving community networks for the prevention of violence and conflict. It also introduces the peace club and its objectives to community members, hence creating an opportunity for recruitment to expand beyond the peace club network. The second stage enables all participants to use the space around them to converse, engage each other and build relationships during the working process. The final stage allows participants to reflect on the value of a nhimbe and how they have benefited from working together for future relations and peacebuilding processes.

Participation

There is usually high attendance and participation in nhimbes where local leaders are involved in the mobilisation process, as opposed to where only community structures are involved, as the presence of local leaders legitimises the nhimbe and the peace club activities. However, there are instances where key stakeholders – such as councillors and traditional leaders – do not attend, because they perceive the nhimbe to be a disguised political gathering. Non-involvement in such activities is an indication of disapproval or fear of being associated with politically interpreted initiatives. Local residents who attend disapproved nhimbes could fall out of favour with their leaders and kinsfolk, or are cautioned against attending such activities in the future.

Other Benefits of Nhimbes

Building community relationships: Nhimbes facilitate relationship-building among community members and conflicting parties. The relationship-building process is perpetual, depending on the frequency of the nhimbes. The more nhimbes are carried out within a specific community, the more local people improve their relationships. The assumption, therefore, is that the more community members interact, the more they are likely to resolve their conflicts and the more they can protect each other from violence.

Reinforcement of community ties: Community ties are improved between the local members themselves, as well as between community leaders and residents. Improved community ties between community leaders and citizens, as well as among locals, increases a sense of community, thus strengthening individual and community security through collectivism.

Restoration of traditional leaders’ responsibilities and authority: The reputation and authority of traditional leaders has been waning over time, particularly due to political polarisation and interference from political parties and partisan government officials. Local members who perceive traditional leaders as partisan political frontrunners have ceased respecting the authority of traditional leaders. On the other hand, some political entrepreneurs have informally assumed the authority of traditional leaders, especially in the allocation of land, distribution of food aid and resolution of community conflicts. Therefore, nhimbes rightfully place traditional leaders in their positions of authority by allowing them to preside over the activity, and by reminding community participants about the traditional African functions of nhimbes.

Conclusion

Nhimbe is a traditional collaborative tool that can be used to advance peacebuilding, violence prevention and conflict transformation. From Heal Zimbabwe Trust’s experience with nhimbes, it is clear that this practice can enable communities to build relations among themselves and with key community decision-makers or stakeholders. While the nhimbe practice was previously used for improving food security and community development, it can be applied to peacebuilding and conflict transformation initiatives. The nhimbe practice can facilitate relationship-building, allow communities to work together, prevent divisions among community members and enhance inclusive community development processes. However, nhimbes work best when the convening grassroots peacebuilding structures – such as peace clubs – are legitimately accepted within the communities of which they are part.

Endnotes

- Muyambo, Tenson (2017) Indigenous Knowledge Systems: A Haven for Sustainable Economic Growth in Zimbabwe Africology. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 10 (3), pp. 172–186.

- Gukurume, Simbarashe (2013) Climate Change, Variability and Sustainable Agriculture in Zimbabwe: Rural Communities. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 14 (2).

- Mawere, Munyaradzi and Awuah-Nyamekye, Samuel (2015) (eds) Harnessing Cultural Capital for Sustainability: A Pan Africanist Perspective. Bamenda: Langaa Publishing House, pp. 85–34.

- Sithole, Pindai Mangwanindichero (2015) Community-based Development: A Study of Nhimbe Practice in Zimbabwe. South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand.

- Tavuyanago, Baxter, Mutami, Nicholas and Mbenene, Kudakwashe (2010) Traditional Grain Crops in Pre-colonial and Colonial Zimbabwe: A Factor for Food Security and Social Cohesion among the Shona People. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12 (6), pp. 1–8.

- Sithole, Pindai Mangwanindichero (2015) op. cit.

- Leedy, Todd (2010) A Starving Belly doesn’t Listen to Explanations: Agricultural Evangelism in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1900 to 1962. Agricultural History, 84 (4), pp. 479–505.

- Holleman, Johan Frederik (1952) Shona Customary Law: With Reference to Kinship, Marriage, the Family and the Estate. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Shutt, Allison K (2002) Squatters, Land Sales and Intensification in Marirangwe Purchase Area, Colonial Zimbabwe, 1931–65. The Journal of African History, 43 (3), pp. 473–498.

- Bessant, Leslie and Muringai, Elvis (1993) Peasants, Businessmen, and Moral Economy in the Chiweshe Reserve, Colonial Zimbabwe, 1930–1968. Journal of Southern African Studies, 19 (4), pp. 551–592.

- Muyambo, Tenson (2017) op. cit.