Introduction

Peacebuilding is both a contested and evolving concept,with no universally accepted definition.[1] Despite being a broadly fluid term without clear guidelines or goals, most scholars agree that the fundamental task of peacebuilding is to improve human security.[2] The term first emerged through Johan Galtung’s peace work. He advocated for the establishment of a peacebuilding system to stimulate long-lasting peace by finding a solution to sources of violent conflicts and enhancing local capacities for conflict resolution and peace management.[3] A report by Boutros Boutros-Ghali entitled ‘An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peace-Keeping’ refers to peacebuilding as ‘an action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace to avoid a relapse into conflict’.[4] A peacebuilding agenda is critical in the realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which advocate for ‘peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, access to justice for all and building effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’.[5]

In the Kenyan context, peacebuilding activities and regulatory frameworks are recognised as vital processes and instruments that are necessary for the achievement of Vision 2030, which is the country’s new development blueprint that aims to transform Kenya into a new industrialising middle-income country providing a high quality of life to all its citizen by 2030. On the one hand, the peacebuilding, conflict management, and security strategy of the political pillar of Vision 2030 underscores the need for promoting peacebuilding and reconciliation, deepening policies and legal and institutional frameworks that promote order in society, as well as institutionalising dialogue between and among communities to promote harmony among racial, ethnic and other interest groups. On the other hand, the social pillar aims at establishing ‘a just and cohesive society that enjoys equitable social development in a clean and secure environment’.[6]

Nyambura Githaiga observes that from a cursory glance, Kenya is not an immediate or apparent choice for a peacebuilding case study.[7] This can be attributed to the fact that peacebuilding studies primarily focus on nations that experienced highly destructive and horrific civil wars and require international intervention. However, Kenya has suffered intermittent and localised destructive conflicts, such as the 1992, 1997, and 2007-2008 election-based violence. Therefore, Kenya offers a peacebuilding case study which is not related to civil war, but part of a tactical response to repeated incidents of local destructive conflicts.[8]

In addition, chronic inter-ethnic, land, ideological, resource-based, cross-border, human-wildlife, and religious conflicts have become part of Kenyan society, thus undermining sustainable development, exacerbating ethnic enmity, and arousing political instability. Therefore, the need for peacebuilding processes towards finding concrete solutions to these conflicts cannot be overemphasised.

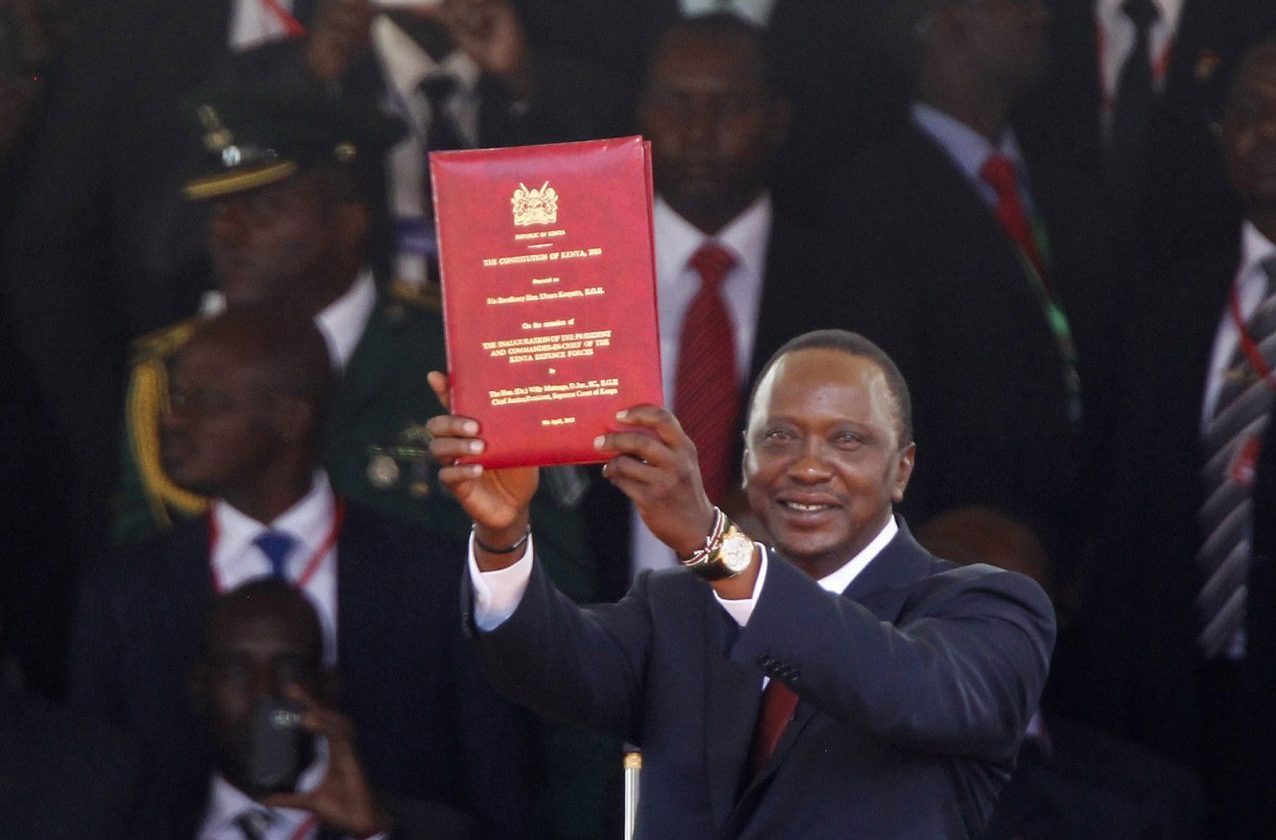

Despite remarkable steps taken by the Government of Kenya and other peacebuilding actors to lessen or prevent conflict occurrence, they are still frequent and intense. Government efforts include the establishment of peacebuilding policies, laws, and mechanisms, among others. This raises a fundamental question: Are existing peacebuilding policies and frameworks which include, but are not limited to, the Constitution of Kenya of 2010, National Policy on Peacebuilding and Conflict Management, National Cohesion and Integration Act No. 12 of 2008, Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Act No. 6 of 2008, and the National Action Plan on Arms Control and Management, effective? Without doubt, there exist critical gaps in policy and institutional and legislative frameworks that require concrete action.

This article, therefore, examines the existing policies and legal frameworks for peacebuilding with the aim of identifying existing gaps that affect the peacebuilding process in Kenya. Careful examination of these instruments can provide useful information needed to strengthen critical regulatory frameworks and enhance conflict management and peacebuilding efforts in Kenya.

Peacebuilding Policies, Legal Frameworks, and Existing Gaps in Kenya

This section deliberates various practices as well as policy and legal frameworks that are essential to peacebuilding in Kenya. It also identifies existing gaps within the policy and legal documents.

The Constitution of Kenya (2010)

A key peacebuilding policy and legal framework is the Constitution of Kenya[9] which clearly outlines a number of stakeholders, such as the judiciary, that have a crucial role in the conflict management and peacebuilding architecture. The preamble to the Constitution underscores the aspiration for Kenyans to live peacefully and in harmony as one undividable, independent nation, irrespective of existing religious, ethnic and cultural diversity.

The advancement of durable peace and security is embodied in the Constitution. Article 238 refers to national security as ‘the protection against internal and external threats to Kenya’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, its people, their rights, freedoms, property, peace, stability and prosperity, and other national interests’.[10] Conflicts are examples of threats to peace and stability which peacebuilding efforts seek to resolve.

With a robust provision that promotes tolerance for diversity, equity, inclusion, and equality, the Constitution creates a platform for addressing challenges that can generate conflict and weaken national cohesion. For example, the Kenyan Constitution promotes the establishment of a devolved system of government which addresses the unequal distribution of economic and political resources that may cause conflicts. Also, it offers opportunities to strengthen platforms, mechanisms, and tools to consolidate progress made in the areas of national cohesion, integration, and peacebuilding and conflict management.[11]

Furthermore, Chapter 10 of the Kenyan Constitution offers salient provisions for the judiciary, including the establishment of the Court of Appeals, High Court, and Supreme Court, which play a crucial role in the resolution of various disputes through official means. In addition, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms critical for conflict resolution are clearly articulated in Article 159 of the Constitution. This article outlines other options for dispute resolution, such as Traditional Dispute Resolution Mechanisms (TDRMs), reconciliation, arbitration, and mediation.[12] While TDRMs, which operate outside the formal legal framework, play a vital role in the resolution of disputes through informal methods, there limited legal frameworks exist to guide their operations due to their informality.[13]For example, the Maslaha system is an informal TDRM exercised by Somali communities in dispute settlement through elders. While the Maslaha system is mostly preferred by these local communities, it has some notable pitfalls, such as unfair rulings, final decisions based on cultural rules which may contradict the Constitution, as well as difficulty in distinguishing what constitutes criminal and civil cases. In addition, the courts are perceived to be focused more on communal relationships at the expense of victims’ needs, who should be at the centre of dispute resolution.[14]

Equally important is Chapter 11 of the Constitution, which articulates the importance of:

- County governments in promoting national unity;

- Marginalised and minority groups’ rights and interest protection;

- Economic and social development and advancement; and

- Equitable distribution of resources among people.[15]

The National Policy on Peacebuilding and Conflict Management (2015)

The National Policy on Peacebuilding and Conflict Management, embraced by the legislature on 27 August 2015, is a product of the review process described in Sessional Paper No. 5 of 2014.[16]This Policy is a collective effort by the Government of Kenya and relevant stakeholders to guarantee stability and create a long-lasting solution to violent conflicts. It provides a mechanism for coordination and synergy-building among key stakeholders involved in peacebuilding and conflict management. It also offers a regulatory framework for resource allocation to government-driven peace interventions that ensure real-time responses to conflict issues.[17]

The six pillars that are central to the realisation of the overall goal of the National Policy include mediation and preventive diplomacy, capacity building, post-conflict recovery and stabilisation, institutional frameworks, traditional conflict prevention and mitigation.[18]

While this policy was intended to offer guidance on the activities of peacebuilding actors, the key challenge lies in its gradual implementation. There is an absence of functional laws for the execution and operationalisation of the National Peacebuilding Policy.[19]To anchor the policy in law, the National Cohesion and Peace Building Bill was first developed in 2016. Despite completing the public consultation process, the Bill remains stuck at the ministerial level and awaits presentation to Parliament by the Cabinet for approval.[20]This, to a greater extent, restricts partnership, networking and coordination among key peacebuilding stakeholders, including civil society. Even though the policy has been utilised as a basis for establishing peace committees at the county level, it has not been systematically rolled out. There is limited ownership of peacebuilding efforts at community and county level due to the inadequate, devolved power and resources. The National Government, private sector, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the capital city of Nairobi largely spearhead peacebuilding activities and hence they are usually centrally driven.[21]

The National Cohesion and Integration Act No. 12 of 2008

The formulation of the National Cohesion and Integration Act was driven by the need to inspire national cohesion and integration by prohibiting ethnic-based discrimination. The Act was created in response to the 2007-2008 electoral violence that resulted in massive loss of lives and livelihoods.

The Act gave rise to the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), whose fundamental role is ‘to facilitate and promote equality of opportunity, good relations, harmony, and peaceful coexistence between persons of different racial and ethnic backgrounds in Kenya and to advise the government with recommendations on possible interventions’.[22]

More recently, the National Cohesion and Peace Building Bill of 2021 was introduced in the Senate, to repeal the Act and rename the NCIC to the National Cohesion and Peacebuilding Commission, with the core mandate of creating a synchronised structure for cohesion and peacebuilding in the country. It is envisaged that the Bill will empower the Commission to tame ‘hate mongers’ or perpetrators of hate speech.[23]

While the NCIC Act was established to strengthen national cohesion and integration among Kenyans and contain hate speech, it is yet to achieve substantial success. The NCIC has been criticised for being a ‘toothless institution’ without the capacity to tame inciters and hate mongers, among others.[24] The NCIC has restricted powers of enforcement and the Act only empowers the Commission to probe racial- and ethnic-based discrimination complaints, and subsequently provide the Attorney-General with recommendations. Despite making crucial recommendations for the prosecution of unruly politicians accused of hate speech as per the law, there have been few, if any, successful prosecutions, notwithstanding substantial evidence of hate speech against accused persons.[25] In addition, there is a lack of political goodwill to promote national cohesion among the political class, and yet they are the main stakeholders.[26] Another weakness of the Act is that it largely concentrates on ethnicity, thus neglecting other target groups for hate speech.[27]

A report on the elimination of all forms of racial discriminationby the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) reveals that while the Act robustly articulates what hate speech entails, there is no clarification on the factors that should be considered when gauging the severity of hate speech and identifying instances that require intervention.[28]

Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Act No. 6 of 2008

The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Act provides for the formation of the Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC). The mandate of the TJRC includes the advancement of peace, national unity, justice, healing, and reconciliation among Kenyans through establishing complete and precise historical data of human rights abuses.

In 2013, the final TJRC report was delivered to the Government of Kenya. The report documented widespread violations of human rights, including injustices under British rule from 1895 to 1963 as well as under independent Kenyan governments, including post-election violence (2007-2008).[29]

It was hoped that full implementation of the recommendations in the TDRJ report would to a large extent address the persistent structural violence drivers in the country. However, an in-depth and critical review of the report published by the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) in 2014 observes that despite ethnicity being flagged as a significant factor in the 2007-2008 election violence, the TJRC report did not sufficiently make robust and policy-relevant recommendations geared towards addressing the ethnic factors that contribute significantly to election violence and have resulted in the deaths of approximately 1 133 people and the displacement of 600 000 individuals during election-related violence.[30]

In addition, the lack of adequate political will to support the execution of the objectives of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Act and the lack of sufficient resources to run its operations, which has forced the Commission to seek loans, are also major obstacles.[31]

The National Action Plan on Arms Control and Management (2006)

The Kenya National Focal Point (KNFP) on Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) was formed in 2002 to accomplish Kenya’s mandate as a Nairobi Protocol signatory. The Protocol is a pact among 11 States in the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes Region on SALW threat reduction, prevention and control.[32]

The KNFP developed the National Action Plan(NAP) on Arms Control and Management, now known as the Strategic Plan, on SLAW in 2006. The NAP consists of a broad set of actions geared towards taming the spread of illicit SALW, including through capacity development, among other actions.[33] While the KNFP has produced a draft national SALW control and management policy, the policy and NAP seem not to have been given the necessary attention by relevant stakeholders in terms of fast-tracking its finalisation and operationalisation. In addition, the disarmament process, which is not widely acceptable to communities, can also be politicised.[34]

While the NAP plays a vital role in curbing SALW, which constitutes a threat to the sustainability of peacebuilding activities, it still faces a lack of adequate financial resources required for the execution of established activities and realisation its objectives. The plan is also geared towards building the capacity of relevant security and civil society stakeholders as a prerequisite action for its successful implementation; however, capacity development is still low. As a result, the National Focal Points (NFPs) struggle with inadequate staff, while the available NFP staff lack the relevant skill sets for the multiplicity of tasks required. The skill sets required include, but are not limited to, research, resource mobilisation, project management, and drafting evidence-based policy recommendations. NFP coordinators are also frequently under-resourced and over-stretched and thus struggle to carry out their roles.[35]

Conclusion and Recommendations

Kenya has made significant strides in developing relevant peacebuilding policies and legal frameworks that are geared towards creating a just, cohesive, and peaceful society. However, a review of the existing peacebuilding policies, legal frameworks, and practices reveals the policy gaps that need to be addressed. It is clear that if the available peacebuilding practices, policies, and legal frameworks are implemented effectively, they would play a crucial role in reducing conflict incidences and enhancing peace. The adoption of a multi-agency approach is necessary for the successful implementation of all peacebuilding efforts.

Recommendations

- The Kenyan National Assembly and the Senate should prioritise the passing of a National Peacebuilding and Conflict Management Bill to anchor the policy in law. This will support the agenda of peacebuilding and conflict management in Kenya to a greater extent.

- The NCIC should be empowered with the requisite capacity to tame hate speech. The legislative arm of the government should fast-track the National Cohesion and Peace Building Amendment Bill into law. This will enable the NCIC to successfully prosecute hate speech.

- The formulation and approval of a legislative framework on the operation of ADR by Kenyan legislators will play a crucial role in providing much-needed guidance on the functioning of ADR in a way that does not violate human rights and/or contradicts the Constitution.

- Sufficient financial resources should be allocated to ensure effective implementation of peacebuilding policies, practices, and efforts by the Government of Kenya and relevant stakeholders.

- The Government of Kenya should employ adequate personnel with the prerequisite experience and skills to manage the NFP secretariats on a long-term basis. This will play a key role in addressing the challenge of staff limitations and skill gaps.

In conclusion, the adoption of a whole society approach in peacebuilding efforts by the Government of Kenya is critical. Therefore, all relevant stakeholders, such as the private sector, NGOs, political and community leaders – who will play a useful role in filling existing gaps in peacebuilding policies and frameworks – and Kenyan citizens, should be brought on board. As a result, the peacebuilding infrastructure will be strengthened.

Sylvan Odidi is a Research Fellow at the Kenya School of Government in Nairobi.

Endnotes

[2] Hazen, Jennifer (2007) ‘Can Peacekeepers be Peacebuilders?’ International Peacekeeping, 14(3), 323–338.

[3] Galtung, Johan (1976) ‘Three Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking, and Peacebuilding’, Peace, War and Defense: Essays in Peace Research, 2(1), 297–298.

[4] Boutros-Ghali, Boutros (1992) ‘An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peace-Keeping’, International Relations, 11(3), 201–218.

[5] Whaites, Alan (2016) ‘Achieving the Impossible: Can We Be SDG 16 Believers?’ GovNet Background Paper No. 2, OECD, Available at: <https://www.oecd.org/dac/accountable-effective-institutions/Achieving%20the%20Impossible%20can%20we%20be%20SDG16%20believers.pdf> p. 14.

[6] Government of Kenya (2007) Kenya Vision 2030: A Globally Competitive and Prosperous Kenya, Nairobi: Government of Kenya, p. xi.

[7] Githaiga, Nyambura (2020) ‘When Institutionalisation Threatens Peacebuilding: The Case of Kenya’s Infrastructure for Peace’, Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 15(3), 316–330.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Government of Kenya (2010) The Constitution of Kenya, 2010, Nairobi: National Council for Law Reporting.

[10] Ibid, p. 144.

[11] Government of Kenya (2011) National Policy on Peace-building and Conflict Management, Nairobi: Office of the President, Available at: <https://www.refworld.org/docid/5a7ad25f4.html> [Accessed 27 January 2022].

[12] Government of Kenya (2010) op. cit.

[13] Mohamed, Zamzam and Muriithi, Peter M. (2020) ‘A Critical Analysis of Maslaha as a Traditional Dispute Resolution Mechanism in North Eastern Kenya’, Journal of Conflict Management and Sustainable Development, 5(1).

[14] Abdi, Maryam (2016) ‘Assessment of Sexual and Gender Based Violence Reporting Procedures among Refugees in Camps in Dadaab, Kenya’, Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi.

[15] Wepundi, Manasseh and Ndung’u, James (2016) The 2030 Agenda: Supporting a More Peaceful Just and Inclusive Society in Kenya, London: Safer World.

[16] Frontier Counties Development Council (FCDC) and Drylands Learning and Capacity Building Initiative (DLCI) (2020) Analysis of the Institutional, Legal and Policy Framework or Peacebuilding and Social Cohesion in the FCDC Region, Nairobi: FCDC and DLCI.

[17] Osula, Mary (2015) ‘Finally! A Peace Policy for Kenya’, Safer World, 4 November,Available at: <https://www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/news-and-analysis/post/174-finally-a-peace-policy-for-kenya> [Accessed 4 February 2022].

[18] Government of Kenya (2014) ‘Sessional Paper No. 5 of 2014 on National Policy for Peacebuilding and Conflict Management’, Nairobi: Ministry of the Interior and Coordination of National Government.

[19] Muragu, Michael and Mpaayei, Florence (2017) ‘Reflection Paper on Strengthening the Peacebuilding Sector in Kenya’, n.p.: Jamii Thabiti Project.

[20] FCDC and DLCI (2020) op. cit.

[21] Muragu, Michael and Mpaayei, Florence (2017) op. cit.

[22] NCIC (2018) Footprints of Peace, Consolidating National Cohesion in a Devolved Kenya 2014-2018, Nairobi: NCIC.

[23] Otieno, Julias (2021) ‘Bill Renames, Empowers “Toothless” NCIC in Bid to Tame Hate Mongers’, The Star, 6 July, Available at: <https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-07-06-bill-renames-empowers-toothless-ncic-in-bid-to-tame-hate-mongers> [Accessed 13 January 2022].

[24] Ibid.

[25] KNCHR (2017) ‘Alternative Report to the Committee on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination’, March, Nairobi: KNCHR, Available at: <https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KEN/INT_CERD_IFN_KEN_27238_E.pdf> [Accessed 4 February 2022].

[26] Kenya Alliance of Residents Association (KARA) (2015) ‘National Cohesion: Kenya is at its Worst Security Index – NCIC Chairman Francis Ole Kaparo’, 22 January, Available at: <https://www.kara.or.ke/index.php/2015-01-22-08-51-09/kara-news/166-national-cohesion-kenya-is-at-its-worst-security-index-ncic-chairman-francis-ole-kaparo> [Accessed 23 January 2022].

[27] Busolo, Doreen and Ngigi, Samuel (2018) ‘Understanding Hate Speech in Kenya’, New Media and Mass Communication, 70, 43–49.

[28] KNCHR (2017) op. cit.

[29] Kenya Transitional Justice Network (KTJN) (2013) ‘Summary: Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission Report’, Nairobi: KTJN.

[30] International Centre for Truth and Justice (ITCJ) (2014) ‘TJRC Final Report Deserves Serious Analysis and Action’, New York: ITCJ, Available at: <https://www.ictj.org/news/ictj-kenya-tjrc-final-report-deserves-serious-analysis-and-action> [Accessed 11 January 2022]; Mutahi, Patrick and Mutuma Ruteere (2019) ‘Violence, Security and the Policing of Kenya’s 2017 Elections’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 13(2), 253–271.

[31] Sum, Abigael (2013) ‘Team Cites Wrangles, Poor Funding as Some of the Obstacles Faced’, The Standard, 23 May, Available at: <https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/kenya/article/2000084236/team-cites-wrangles-poor-funding-as-some-of-the-obstacles-it-faced> [Accessed on 10 February 2020].

[32] Githaiga, Nyambura (2020) op. cit.

[33] Government of Kenya (2006) Kenya National Action Plan for Arms Control and Management, Nairobi: Government of Kenya, Available at: <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/124869/Kenya-National-Action-Plan-2006.pdf> [Accessed 10 February 2020].

[34] FCDC and DLCI (2020) op. cit.

[35] Ndung’u, James and Wepundi, Mannsseh (2011) ‘Controlling Small Arms and Light Weapons in Kenya and Uganda: Progress So Far’, Working Paper, May, Saferworld, Available at: <https://www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/publications/565-controlling-small-arms-and-light-weapons-in-kenya-and-uganda>