Introduction

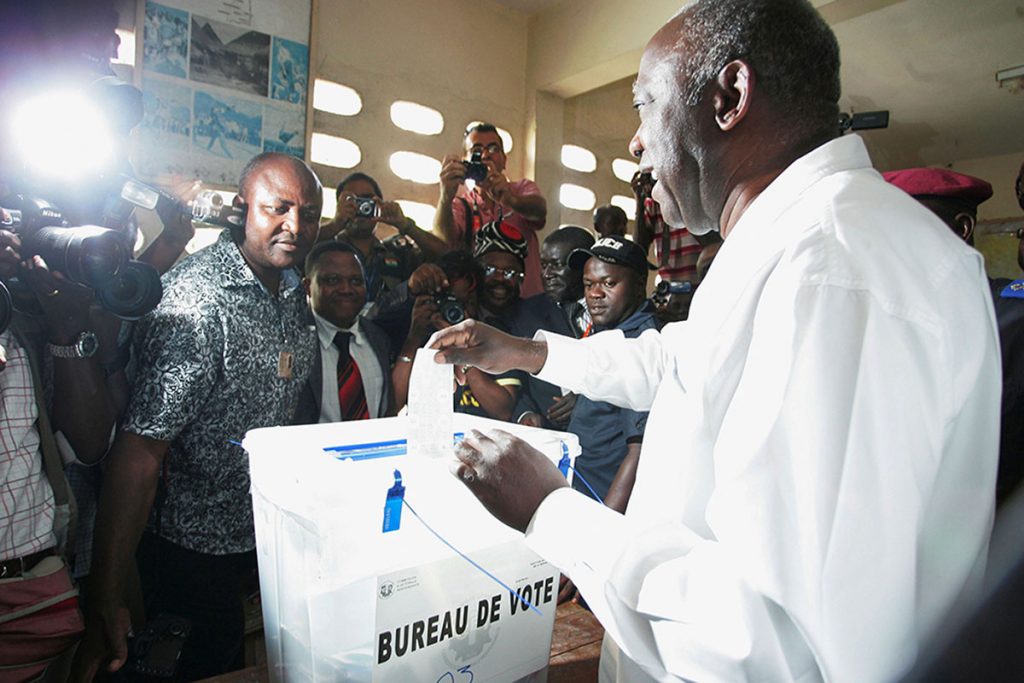

Côte d’Ivoire’s presidential election on 31 October 2020 marked the fifth presidential election held in the country since the death of the “pere foundateur de la nation” (father of the nation), Félix Houphouët-Boigny, in 1993. The election was held in a tense political and volatile security atmosphere, driven by opposition protests against President Alassane Ouattara’s third-term candidacy, which was a breach of the 2016 constitution. The political contest among the political stakeholders also bordered on matters around the electoral code, the voter register, implementation of the constitutional reforms and the composition of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), which opposition parties denounced as non-inclusive, unbalanced and partisan.[1] The inability of the ruling party and the opposition parties – which formed a common political front, led by Henri Konan Bédié – to reach common ground in addressing these issues led to a series of protests, which escalated into violence across the country. On the eve of the election, Bédiéand Pascal Affi N’Guessan, the two major opposition candidates, reneged their participation in the election and called on their supporters to block the election.

The election result declared by the IEC proclaimed Ouattara as the winner, having amassed 94.27% of the votes cast. N’Guessan got 0.99%, Bédié was credited with 1.66% and Kouadio Konan Bertin obtained 1.99%.[2] These results, which were ratified by the Constitutional Council on 9 November 2020, as stipulated in the constitution, endorsed President Ouattara as the winner. However, N’Guessan, on behalf of the opposition parties, announced his non-recognition of Ouattara’s victory and thereby installed a National Transitional Council, with Bédié as the president.Protests by opposition parties and their supporters led to violence, which resulted in about 85 deaths recorded in localities including Yopougon, Bonoua, Mbatto, Bongouanou, Daoukro and others.[3]

It is important to note that the 31 October 2020 election was organised against the backdrop of a history of electoral violence in Côte d’Ivoire. The 2011 post-electoral crisis resulted in the death of about 3 000 people.[4] Despite this, Côte d’Ivoire regained relative stability and enabled economic prosperity, and huge investments were recorded in the country. Côte d’Ivoire is a major economic player in the region. For close to a decade, the economic indices of the country have been impressive, with an average record of 8% growth annually.[5] Consolidating this relative peace and economic development raised the stakes in the recent election in Côte d’Ivoire.

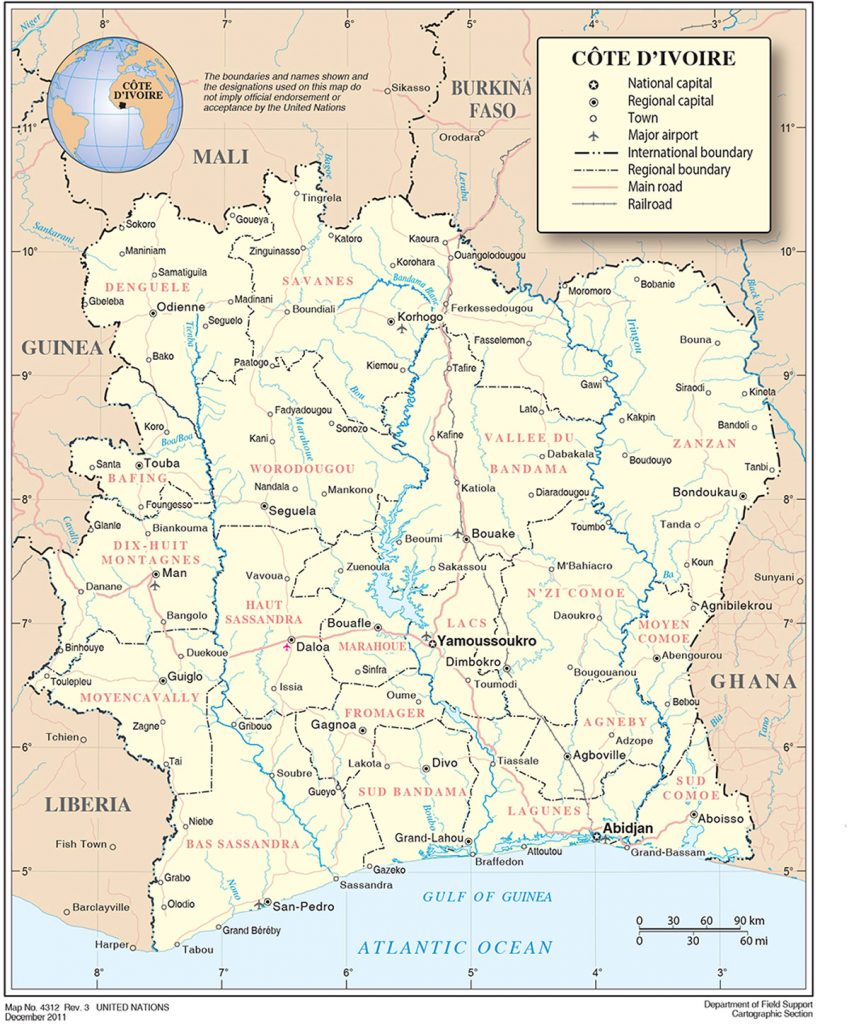

Côte d’Ivoire is also a strategic and central country in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region. The impressive economic prosperity recorded in the country recently has impacted positively on the fortunes of the region. More importantly, Côte d’Ivoire shares borders with a number of fragile countries including Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Liberia. Burkina Faso and Mali are experiencing deadly attacks by terrorist groups. A deep crisis in Côte d’Ivoire could destabilise the region, due to the volatile and degraded security situations in Burkina Faso and Mali.

This article provides an overview of the trends of elections in Côte d’Ivoire. Specifically, it analyses the major dynamics that have characterised elections by examining the patterns of votes and voting, political alliances and the current conflict atmosphere in Côte d’Ivoire. The article also examines ECOWAS’s efforts to manage and prevent conflict in Côte d’Ivoire. The article concludes with recommendations to consolidate democracy, peace and security in Côte d’Ivoire.

Election Trends and Dynamics in Côte d’Ivoire

Since the death of Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire has been ruled by three presidents: Bédié, Laurent Gbagbo and Ouattara, who were elected at polls, while Robert Guéï became president after the 24 December 1999 coup d’état.

Bédié, as the president of the National Assembly, succeeded Houphouët-Boigny after the latter’s death in 1993, in conformity with the constitutional requirement. President Bédié won the 1995 presidential election, while Gbagbo and Ouattara boycotted the election in protest against the introduction of an exclusionary principle of Ivorite into the electoral code. The principle of Ivorite stipulates that candidates for the presidency must be of Ivorian origin, born of a father and a mother of Ivorian origin. This principle was a political tool allegedly used by Bédié to block Ouattara, whose father was allegedly a Burkinabe, from the contest. While this further formalised the perceived exclusion of “northerners” in Ivorian politics, Bédié was however removed from power in a coup d’état on 24 December 1999.

The 2000 presidential election was conducted against the backdrop of the 1999 coup d’état. The late General Guéï, who was installed as president after the coup, and Gbagbo were the main contenders in the 2000 election. The candidacies of Ouattara and Bédié had been rejected by the constitutional court on the eve of the election in 1999. Gbagbo emerged as winner and was sworn in as the president of Côte d’Ivoire in a chaotic atmosphere orchestrated by Guéï’s refusal to concede defeat. Ouattara and Bédié also rejected Gbagbo’s victory, on the grounds that the electoral contest was not inclusive. What is clear is that the trio of Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara continue to hold sway in the political development trends in the country.

The 2010 presidential election was a landmark electoral contest in the annals of the Ivorian political trajectory. The election was held following a protracted rebellion, which was marked by a country divided into the north and south. After the adoption of several peace accords, the candidacies of the three principal political figures (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara), among others, were validated to contest the 2010 presidential election. The turnout rate for the election was the most impressive since 1993 (see Table 1). However, the contestation of the run-off results between President Gbagbo and Ouattara pushed Côte d’Ivoire into violent conflict, with over 3 000 people killed.[6] The 2015 presidential election was held in a calmer political atmosphere, with President Ouattara seeking re-election. President Ouattara won the election under a unified Rally of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP).

Table 1: Presidents in Côte d’Ivoire (1993 to date)

| President | Year in office | Length of presidency | Political party |

| Henri Konan Bédié | 1993–1998 | 5 years | Democratic Party of Ivory Coast – African Democratic Rally (PDCI-RDA) |

| Robert Guéï | December 1999–October 2000 | 10 months | Military/Transition |

| Laurent Gbagbo | 2000–2010 | 10 years | Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) |

| Alassane Ouattara | 2010 to date | 10 years to date | RHDP |

A cursory look at the electoral trajectory in Côte d’Ivoire shows a trend that can be summarised in four points. First, Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara have continued to dominate the political space for over 25 years. Second, Côte d’Ivoire has never experienced a peaceful transfer of power. The 1995 presidential election, won by Bédié, was interrupted by a coup d’état in December 1999, and the second republic, which featured the 2000 election, won by Gbagbo, was abruptly interrupted by a rebellion in 2002. Significant post-electoral violence erupted after the 2010 election. With the exception of the 2015 election, the electoral trajectory in Côte d’Ivoire has been marred by violence. This experience has not been favourable for deepening of democratic consolidation, peace and security in the country.

Third, the outcome of elections clearly reveals the sociopolitical configuration of the national electoral map in Côte d’Ivoire. Regional and ethnic patterns define voter alignment. Ouattara remains the dominant political figure in the north (Dioula), while Bédié dominates the centre (Baoulé) and only Gbagbo appears to have moved beyond his traditional (Bété) ethnic stronghold in the west, winning significant support in the south (Abidjan) and east of the country.[7]

Fourth, the principle of inclusivity/exclusivity is significant in determining the sustainability of the regime in Côte d’Ivoire. The disqualification and subsequent boycott of key candidates in the 1995 and 2000 presidential elections resulted in military incursion and invasion to disrupt democratic order. Conversely, the 2010 presidential election was the first time the three political protagonists (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara) could contest in Côte d’Ivoire, and the election was not only peaceful but the turnout was the all-time highest in Ivorian electoral history. President Ouattara, under a unified RHDP (coalition comprising Bédié, Guillaume Soro, Albert Toikeusse Mabri and so on), emerged winner in a run-off.

The 2015 presidential election was unique, as President Ouattara was the only one in the contest among the three key political figures, and the aftermath of the election was peaceful. President Ouattara was adopted as the sole candidate of the unified RHDP, as Gbagbo was facing trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. The implication is that it takes an alliance of two out of the three key political protagonists (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara) to convincingly win a presidential election in Côte d’Ivoire. The 31 October 2020 presidential election was the first time that President Ouattara contested against the other two major traditional political parties, PDCI-RDA and FPI. The opposition parties adopted Bédié as their rallying point and de facto leader.

The 2020 election was expected to be keenly contested among the three major political parties – RHDP, PDCI-RDA and FPI – considering their historical rivalry. The incumbent president and flagbearer of the RHDP, President Ouattara, was seeking re-election for a third term, and was expected to take on Bédié and N’Guessan. This would have marked the second time that President Ouattara and Bédié would have faced each other, with President Bédiéhaving defeated Ouattara in 1995, although Ouattara boycotted the election. President Ouattara, under a unified RHDP, defeated N’Guessan in the 2015 election – so the 2020 election would have marked a second go-around of N’Guessan against President Ouattara. While Bertin, a PDCI-RDA dissident, was unlikely to make a significant impact on the overall outcome, reasonably, his candidacy was potentially injurious to PDCI-RDA. However, on the eve of the election, Bédié and N’Guessan, the two major opposition figures, reneged their participation in the election and called on their supporters to block the polls.

Voting Pattern

Voter turnout is one of the crucial indicators of how citizens participate in the governance of their country[8]. Higher voter turnout is, in most cases, a sign of the vitality of democracy, while lower turnout is usually associated with voter apathy and mistrust of the political process.[9] Forming of alliances among the three political protagonists (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara) and respect for the principle of inclusivity has continued to determine the voting pattern in Côte d’Ivoire.

In 1995, the turnout rate in the election was a little above average. This could be attributed to the boycott staged by Ouattara and Gbagbo due to the insertion of the Ivorite principle in the electoral code, allegedly to prevent Ouattara from taking part in the contest. Also, Table 2 shows that despite an increase in the number of registered voters – from 3 756 926 in 1995 to 5 475 143 in 2000 – turnout declined from 52.32% to 37.42% in the 2000 presidential election. This decline can be predicated on the boycott staged by Ouattara and Bédié, due to the disqualification of their candidacies by the constitutional court over issues of nationality and financial misconduct respectively.

Table 2: Voter turnout and number of registered voters in Côte d’Ivoire (1995–2020)[10]

| Year of election | Total registered voters | Voter turnout % |

| 1995 | 3 756 926 | 52.32 |

| 2000 | 5 475 143 | 37.42 |

| 2010 | 5 780 804 | 81.12 |

| 2015 | 6 301 189 | 52.86 |

| 2020 | 7 495 082 | 53.90 |

The 2010 election had the most participation, as the three key political protagonists (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara) participated in the election. Table 2 shows that this election saw the highest turnout (81.12%) recorded since 1993. This can be attributed to the fact that none of these key political actors were unjustly disqualified from participating in the election.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that despite the increase in the number of registered voters – from 5 780 804 in 2010 to 6 301 189 in 2015 – turnout declined from 81.12% to 52.86% in the 2015 presidential election. This sharp decline can be attributed to two reasons. First, the continued trial of Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé in The Hague frustrated genuine efforts aimed at reconciling various ethnic groups after the 2011 post-electoral crisis. Hence, Gbagbo’s supporters and kinsmen boycotted the 2015 election. Second, Bédié’s popularity waned within the PDCI-RDA as his call for the adoption of President Ouattara as the sole candidate of the unified RHDP created dissidence in the PDCI-RDA. Three other presidential candidates – Charles Konan Banny, Essy Amara and Kouadio Konan Bertin – emerged as dissident candidates of the PDCI-RDA to contest the 2015 presidential election.

With respect to the 2020 presidential election, registered voters increased from 6 301 189 to 7 495 082, a 18.9% increase. Despite this hike in the number of registered voters, voter turnout for the elections was not only unimpressive but also controversial. The IEC pegged the total turnout at 53.90%, but local and international civil society organisation (CSO) observation groups – such as the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa(EISA), the Carter Center and Indigo – maintained a contrary position. This could be justified due to the fact that only 41.15% of voter cards were collected in advance of the polls.[11] In addition, the EISA-Carter Center International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) noted that the turnout at the polls showed strong disparities across the country, with relatively high rates in the north and lower rates in the centre and west, and were variable in the south of the country.[12] The IEOM also noted “concerns that the overall context and process did not allow for a genuinely competitive election”.[13] This unimpressive turnout was largely caused by the opposition’s call for active boycott of the electoral process.

Conflict Atmosphere in Côte d’Ivoire

The recentt political atmosphere in Côte d’Ivoire is characterised by electoral violence. At least 85 people have been killed thus far in election-related violence[14] between supporters of incumbent President Ouattara, security forces and opposition protesters. As of 2 November 2020, more than 3 200 Ivorian refugees had arrived in Liberia, Ghana and Togo.[15] The complex interaction of structural and direct violence were the causes of the electoral violence in the 2020 presidential election. Political instability and threats to peace and security in Côte d’Ivoire have been stimulated by structural factors such as lack of respect for constitutionalism, a crisis of legitimacy, the politics of exclusion, challenges of internal party democracy, a compromised judiciary, disrespect for the rule of law and human rights, challenges of reconciliation, democratic control of the armed forces and the role of the superpowers.[16] Emerging triggers of conflict in Côte d’Ivoire have been underpinned by factors such as inflammatory and inciting statements, civil disobedience, violation of human rights, operation of political militia and armed groups, dissemination of fake news and misinformation across communities.

Inflammatory and Inciting Statements

In the prelude to the 31 October 2020 polls, politicians from both the parties, in power and opposition, indulged in inflammatory and inciting statements. Ranking political figures were not exempt from this dangerous act. The prime minister, Hamed Bakayoko, publicly requested President Ouattara’s permission to allow the RHDP’s supporters to respond to the provocation of the opposition parties. Some key figures in the opposition parties have also revamped the old debate on the xenophobic exclusionary principle of Ivorite. While these inciting statements heightened the already-tense political atmosphere, due to the multi-ethnic nature of Côte d’Ivoire, it also sparked intercommunal clashes in some communities. In fact, about 15 people were killed in intercommunal violence in August and September 2020 across the country after Ouattara announced his intention to run for a third term.[17] Recently, intercommunal clashes occurred in Bongouanou, the stronghold of opposition candidate and former prime minister, N’Guessan, as residents from different ethnic groups fought with machetes while houses and shops were set on fire.[18]

Since the ruling party and opposition parties have agreed to engage in dialogue, inciting and inflammatory statements should be curbed by all means possible. Key peace actors, both within and outside the country, are critical in curbing this challenge. For full effectiveness, ECOWAS has a role to play in impressing and holding accountable political leaders indulging in inciteful speeches, given the regional body’s sanction role and power. Politicians should maintain issue-based and peace messaging in public discussions and political debates.

Civil Disobedience

The call for civil disobedience by the opposition parties impacted heavily on the electoral process. It manifested in the withdrawal of the representatives of the PDCI and FPI from the IEC in protest by the opposition platform against Ouattara’s third-term ambition. Subsequently, opposition parties renounced their participation in the last election. Also, opposition party supporters were not only called to refrain from participating in the electoral process, but were also asked to undertake actions geared towards impeding the conduct of the 31 October 2020 election. Specifically, opposition parties were directed to obstruct the distribution of the voter cards, as well as other activities. Consequently, several polling stations were ransacked in opposition strongholds on election day and, following the election, election materials were burned. In the eastern town of Daoukro, protesters erected roadblocks. Meanwhile, teargas was used to stop demonstrators who gathered where the president cast his ballot in Abidjan. Tensions generated by the opposition parties’ rioting obstructed electoral processes in some areas such as Daoukro, Bongouanou, Yopougon and Gangnoa. The implication of civil disobedience by the opposition parties had far-reaching effects on the conduct of peaceful elections in Côte d’Ivoire.

After the polls, the opposition party announced the establishment of a National Transitional Council. Headed by Bédié, the Council is expected to facilitate the organisation of more inclusive and transparent elections in the shortest period of time. However, legal action by the government and the current build-up to the holding of a dialogue among the political stakeholders has killed the momentum in the operationalisation of the National Transitional Council.

Violation of Human Rights

Human rights violations have continued to mar the electoral period in Côte d’Ivoire. There have been arbitrary arrests and a crackdown on members of opposition parties and CSOs. Pulchérie Edith Gbalet and her two colleagues, members of the Alternatives Citoyenne Ivoirienne (ACI), were arrested and detained on 15 August 2020 after they called for protests against the third-term bid of President Ouattara. The arbitrary arrest and detention of N’Guessan and other opposition leaders in the aftermath of the October 2020 election is a human rights concern.

In addition, there were serious concerns about restrictions on civil liberties, freedom of expression, and the right to vote and be elected. The government banned civil protests throughout the country. This ban did not allow citizens to exercise their fundamental freedoms in this critical period, and these freedoms continue to be violated.

The disqualification of key political actors was another serious human rights concern. Albert Mabri Toikeusse, Mamadou Koulibaly and Marcel Amon Tano were disqualified by the constitutional court on the grounds of their failure to accrue the requisite number of signatories from their supporters across the country, in line with the parrainage policy. This policy requires every presidential candidate to be adopted by at least 1% of the registered electorates in 17 out of the 31 regions across the region.[19] However, Toikeusse had contested for the presidential election under Union pour la Democratie et la Paix en Côte d’Ivoire (UDPCI) in 2010, winning 2.3% of the vote, whilst Koulibaly, as the flagbearer of Liberte et Democratie pour la Republique (LIDER), polled just 0.1% in the 2015 presidential election.[20] While these candidates were unlikely to make a significant impact on the overall outcome, their exclusion was not in line with inclusive democratic practices and constituted an affront to their fundamental human rights.

Political Militia and Armed Youth

The tense political atmosphere being experienced in Côte d’Ivoire is partly fuelled by the activities of “microbes” and other rival militias and armed youth groups associated with political parties. Microbes are armed youth who participated in the struggle for the restoration of Ouattara’s mandate during the post-electoral crisis of 2011. Despite the government’s efforts towards the microbes through the disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programme following the 2011 post-electoral crisis, these armed groups have remained active and perpetrated violence in the period leading to, during and after the recent election. A clash between supporters of the ruling party and supporters of the opposition parties in Dabou between 19 and 21 October 2020 resulted in 16 deaths and 67 people injured.[21]According to Côte d’Ivoire’s Minister of Security and Civil Protection, Diomandé Vagondo, about 70 people were arrested between 10 and 14 August 2020 for “disrupting public order, incitement to revolt, violence against law enforcement agents and destroying property”.[22]

Fake News and Misinformation

Access to the internet and social media provides citizens opportunity to engage in public discourse, participate in the voting process and hold public office holders accountable; all of which are basic ingredients of a democratic society. However, false information, rumours and doctored videos have been used to incite violent protest and rioting during electoral periods in Côte d’Ivoire. Violence in Mbatto, which claimed many lives, was fuelled by the sharing of doctored videos, inciting one community against the other, on WhatsApp and Facebook.

ECOWAS and the Prevention of Conflict in Côte d’Ivoire

Realising the strategic importance of the election in Côte d’Ivoire to the political, economic and geostrategic dynamics of the region, ECOWAS activated its peace and security architecture to prevent and manage threats to the conduct of peaceful, credible elections whose outcome will be accepted by Ivorian political stakeholders.

The ECOWAS peace and security intervention in Côte d’Ivoire can be divided into two parts. The first part comprises ECOWAS’s electoral support. This electoral support, made up of electoral assistance and the deployment of election observation missions, was implemented as a structural conflict prevention measure. In line with the relevant provisions of the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, ECOWAS deployed an Exploratory and Evaluation Mission and Long-term and Short Term Observation Missions to assess the level of preparedness of the electoral management bodies and political actors, as well as the legal framework under which the elections would be conducted; observe political developments and activities in the period leading to the election; and observe the voting process on election day. These missions were complemented by technical assistance to enhance the capacities of political parties, media practitioners and the IEC, provided by the ECOWAS Commission.

The second part constitutes preventive diplomacy measures – notably, the Joint High Level Solidarity Mission executed by the ECOWAS, the African Union (AU) and the United Nations (UN) from 4 to 7 October 2020. The Joint Mission, among others, impressed on the IEC the need to deepen engagement with the candidates to find lasting solutions to issues around voter registers and the composition of the Central Electoral Commission. The Joint Mission also called on contending political parties to embrace dialogue as a tool to address their grievances, to ensure that the 31 October 2020 polls were held in an atmosphere that was peaceful and stable. However, lack of confidence and mutual mistrust among the major political actors hampered the organising of a dialogue with a view to fostering consensus and compromise on key contentious issues. The situation necessitated the need for a third-party mediator/facilitator to facilitate and/or mediate among the ruling party and opposition parties.

In addition to the Joint Mission, the Ministerial Mission on Preventive Diplomacy was deployed to Côte d’Ivoire from 17 to 19 October 2020. The Ministerial Mission was remarkable in its recommendations. It impressed on the opposition parties the need to reconsider their decision to boycott the electoral process and the call for their supporters to embark on civil disobedience in protest to Ouattara’s third-term bid. Due to the growing dissemination of hate and inflammatory speeches, the Ministerial Mission called on all political stakeholders to exercise restraint in their political outbursts that invoked old rhetoric, capable of reawakening divisive sentiments of the past and inciting violence. These preventive diplomacy missions were timely in dousing tensions in the Ivorian polity. However, little was done to facilitate discussion among the contending ruling party and opposition parties.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The political trajectory of Côte d’Ivoire has been characterised by electoral violence, which has often resulted in the loss of lives and property. The peaceful transfer of power has eluded the country since 1993. The hope of consolidating stability and development was dashed by the contentions and violence that marred the 2020 presidential election. Issues around the implementation of constitutional and electoral reforms, as well as other structural challenges, have been the major causes of electoral violence in Côte d’Ivoire. These issues continue to undermine democratic consolidation and the preservation of peace and security in the country.

ECOWAS has been a major regional actor engaged in the consolidation of democracy, peace and security in Côte d’Ivoire. Operationalising its peace and security architecture has brought about considerable impact in dousing tensions, mitigating further escalation of violence and encouraging political actors to embrace dialogue. ECOWAS needs to reinforce its efforts in Côte d’Ivoire by deploying a facilitator/mediator to facilitate discussion and/or mediate peace between the incumbent government and opposition parties.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are provided as a possible way forward to mitigate against threats to democracy, peace and security in Côte d’Ivoire.

For the government of Côte d’Ivoire

- Establish an Inquiry Commission to investigate responsibility for human rights violations, acts of violence and cases of murder, particularly the 85 persons who reportedly died during the electoral period.[23]

- Commit genuinely to political dialogue, initiated by President Ouattara to address grievances and attain political solutions to the post-electoral crisis the country is presently facing.

- Impress on members of the cabinet and leadership of parties in power, and opposition, to exercise restraint in inflammatory and hate speeches on both social media platforms and traditional media spaces.

- Contain the activities of microbes and armed youth groups associated with both the ruling parties and opposition parties to prevent further escalation of intercommunal clashes.

- Ensure the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners, members of the opposition parties and civil society actors, detained for holding different political opinions in the exercising of their freedom of expression.

- Ensure the safe return of all political actors in exile, particularly Gbagbo, Guillaume and Goudé, to foster genuine reconciliation, stability and lasting peace in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Abrogate extant law, regulations and policy that infringes on freedoms and contradicts principles of human rights.

For political parties

- Embrace dialogue and other peaceful measures to address any differences emanating from the electoral processes in the period leading to, during and after elections.

- Refrain from civil disobedience and embrace legal means to agitate and advocate for the respect of freedom, human rights and political opinions.

- Resist the propagation of fake news, inflammatory and inciting speeches on both news media and traditional media outlets to douse tensions in the polity, particularly in local communities across the country.

For armed and security forces

- Remain neutral, impartial and professional in the discharge of duties of security and defence of the territorial integrity of Côte d’Ivoire.

- Refrain from any attempt to wrest power from a democratically elected government in Côte d’Ivoire.

For ECOWAS

- Encourage the government to continue the political dialogue with the opposition parties to attain political solutions to address all the contentious issues emanating from the electoral process in Côte d’Ivoire. In this regard, ECOWAS should dispatch a facilitator/mediator to facilitate discussion and/or mediate between the incumbent government and opposition parties.

- Impress on the opposition parties the need to continue to embrace constitutional means and established legal means to resolve their grievances.

- Reconfigure its extant normative and legal instruments on democracy and good governance to address emerging political reforms that favour the undemocratic retention of political power.

Mubin Adewumi Bakare is a Human Rights and Rule of Law Advisor in the Democracy and Good Governance Division at the ECOWAS Commission.

Endnotes

[1] Mubin, Adewumi (2020) ‘Threats to Credible Elections in Côte d’Ivoire: An Overview’, Centre for Democracy and Development, Available at: <https://cddelibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/THREATS-TO-CREDIBLE-ELECTIONS-IN-COTE-D’IVOIRE-2.pdf> [Accessed 3 November 2020].

[2] Abidjan.Net (2020) ‘Présidentielle 2020: Proclamation des Résultats Provisoire’, 2 November, Available at: <https://www.abidjan.net/ELECTIONS/presidentielle/2020/> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

[3] Baudelaire, Mieu (2020) ‘Côte d’Ivoire: Ouattara Reins in his Troops at an Emergency Meeting’, The Africa Report, 16 November, Available at: <https://www.theafricareport.com/50732/cote-divoire-ouattara-reins-in-his-troops-at-an-emergency-meeting/> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

[4] Human Rights Watch (2020) ‘Côte d’Ivoire: Post-Election Violence, Repression’, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/02/cote-divoire-post-election-violence-repression> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

[5] The World Bank (2020) ‘Côte d’Ivoire Overview’, Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cotedivoire/overview> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

[6] Human Rights Watch (2020) op. cit.

[7] Results of presidential elections reveal the regional and ethnic voting pattern in Côte d’Ivoire. When, in 2010, the three principal political figures (Bédié, Gbagbo and Ouattara) were allowed to contest, Bédié came third, accruing votes largely from the Baoule-dominated region; Ouattara emerged second, amassing votes largely from his Dioula – northern bastion; while Gbagbo was the only candidate to get votes beyond regions considered to be his support base.

[8] Centre for Democracy and Development (2020) The Outlook for Ondo: Votes and Violence, October.

[9] Solijonov, Abdurashid (2016) ‘Voter Turnout Trends Around the World’, International IDEA, Available at: <https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/voter-turnout-trends-around-the-world.pdf> [Accessed 22 November 2020].

[10] IFES Election Guide (2020) ‘Election Overview in Côte d’Ivoire’, Available at: <https://www.electionguide.org/countries/id/54/> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

[11] The Carter Centre and EISA (2020) ‘Preliminary Statement of the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM), Côte d’Ivoire’, Available at: <https://www.cartercenter.org/news/pr/2020/cote-divoire-110220.html> [Accessed 10 November 2020].

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Baudelaire, Mieu (2020) op. cit.

[15] UNGHR (2020) ‘Report on Post-electoral Violence in Côte d’Ivoire’, Available at: <https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2020/11/5fa118a44/ivorians-flee-neighbouring-countries-fearing-post-electoral-violence.html> [Accessed 22 November 2020].

[16] Mubin, Adewumi (2020) op. cit.

[17] Aljazeera (2020) ‘Ethnic Clashes in Ivory Coast Opposition Stronghold’, 18 October, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/18/ethnic-clashes-in-ivory-coast-opposition-stronghold-ahead-of-poll> [Accessed 20 November 2020].

[18] Ibid.

[19] Government of Côte d’Ivoire (2000) Electoral Code. LOI N° 2000-514 DU 1ER AOUT 2000.

[20] African Elections Database (2020) ‘Elections in Côte d’Ivoire’, Available at: <https://africanelections.tripod.com/ci.html#2010_Presidential_Election> [Accessed 23 November 2020].

[21] Amnesty International (2020) ‘Côte d’Ivoire: Police Allow Machete-wielding Men to Attack Protesters’, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/08/cote-d-ivoire-police-allow-machete-wielding-men-to-attack-protesters/> [Accessed 21 November 2020].

[22] Ibid.

[23] Baudelaire, Mieu (2020) op. cit.